- Doing Good

- Goodness Gracious

- Pain Relievers

- Call It Human Nature

- Storylines

- The Sickness Swing

- The Sound of Sublime

- Moving Pictures

- Body Language

- A Quiet Incarnation

- Giving Upward

- Dauntless Luminescence

- The Shining Joy of Falling Flat on Your Face

I almost thumbed past it. A guy I know who’d started a flower-delivery company after college posted a blank United States map on social media a few days before Christmas with this entreaty: “Who knows a nurse or doctor that could use a Holiday wreath as thanks for their service? Please DM me.”

I shot off the name and address of a close friend — a woman I’d met in New Orleans not long before the hellacious 2005 hurricane — who now, in Minneapolis, helps deliver babies, including some whose mothers have COVID-19.

An hour later, I couldn’t let it rest. I tapped out another message: “She and I did the whole Katrina thing together way back when, and we now talk often of how this moment feels similar, that all her screaming from the front lines about how bad things are seems to vanish before reaching anyone’s ears.”

Sending my Notre Dame pal the basics almost certainly would have done the trick. He hadn’t asked for the backstory; he didn’t need to be convinced. But given the chance to share a little more, to introduce him in a deeper way to this devoted nurse and mother, I couldn’t resist.

It’s been a long season of disconnection. I was a runner before the pandemic, but in those weeks after everything shut down last March, I avoided catching the eyes of other masked joggers and dog-walkers in my neighborhood. I feared I might mistakenly imply a desire for closer contact and, with it, take a perilous step toward the zone where deadly germs float free.

Before life changed, my days had been filled with near-constant physical contact: hugging the receptionist at our son’s preschool in downtown Atlanta; chatting with kids about Minecraft en route to soccer practice; colleagues stopping at the gumball machine stocked with peanut M&M’s (and a jokester’s occasional Skittle) next to my desk in CNN’s main newsroom, where hundreds of people used to shuffle in and out at all hours, trading out spots at work stations to meet our 24/7 obligation.

Sharing people’s experiences is a key part of my work as an editor on the national digital news desk. Huddling — now by phone, of course — with our reporters, I’m forever imploring, “I want to hear from” someone who is living the stories heralded by our headlines. Yes, we need the official line and the data — coronavirus hospitalization and death rates, voter turnout statistics, protest arrest numbers — but we also need voices.

I want to hear — in his own words — from the veteran who feels the Arizona emergency room where he now fights COVID-19 is “a lot worse than being in Iraq, just because when you’re in a war zone, you can leave.” I want to hear from the voter in rural Georgia who, in 2015, took action when he suspected the local elections board was “making Black votes disappear.” I want to hear from the activist who took to the streets in a pandemic. “I don’t care if I lose my life,” she said, “if that means my nieces and my nephews won’t have to deal with someone invalidating them because of the color of their skin.”

When I hit the “publish” button, I hope it serves as an act of person-to-person introduction, albeit on a massive scale. I hope it might, for our readers, offer a fuller, truer view of how the world operates and, for our sources, serve the critical human need to be heard. I hope it fosters a stronger sense of being connected — and builds a bit more empathy everywhere.

When Rayshard Brooks was killed last June and protests erupted within earshot of our corner of Georgia’s capital, my husband and I explained to our sons that a father who’d parked his car to rest had been awakened by the police and, within minutes, slain by an officer. We explained how race may have played a part. But it didn’t seem to resonate until we explained how one of their classmates hadn’t slept those nights. “Why do they hate us?” that young neighbor wanted to know. I asked her mother if we could share her woeful question with our sons. When we did, they cried, too.

Months later, in November, the same girl held up an iPad to make her own video of Senator Kamala Harris’ victory speech. She said, “Mommy, the VP looks like me! She’s warming the seat for me to be the president!” Her mother texted me the moment, along with a snapshot. I showed it to my husband and my mother — I couldn’t keep that to myself, either.

History is happening all around us. It’s in news headlines and social media posts and conversations shouted across city blocks before we huddle back into our quarantine bubbles. Some have taken to chronicling these historic months to ensure the strange, tedious details aren’t forgotten. That’s important and admirable. For me, the goodness resides in not just the stories we keep but the stories we share, right now, when fresh perspectives could alter how everyone perceives a highly volatile world and behaves in it. It’s not networking — connecting to satisfy some endgame — but a chance to listen and reconsider.

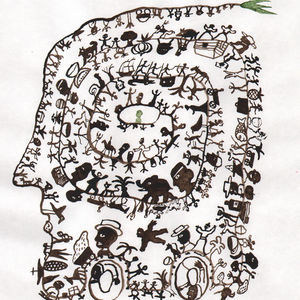

I think sometimes of a Venn diagram, the blossom of circles that helps visualize differences and similarities. Overlapping sections might show what whales and fish have in common, or what’s akin among a pirate, a ninja and a zombie. I imagine in those circles the people I’ve known: my family, former classmates and teachers, neighbors in cities across the country, current and former colleagues, and strangers who’ve shared their thoughts with me through the news stories I’ve written and edited over the years.

Then I imagine a tiny version of myself standing in the intersection, red-faced and breathless, pushing hard on the sides to stretch the shared space in between them all. If someone’s experience was important enough, powerful enough to give me pause, I would be incompetent to hoard it. I should find a way — respectfully, responsibly — to share it, whether with an audience of millions or another trusted friend. The potential may be boundless. Midwifing a connection might even nurture something deeper than a thoughtful shift in one’s point of view.

Not long ago, a woman with whom I went to grade school found a photo of herself that had appeared almost four decades ago in a Chicago newspaper. Her family had been victimized in a notorious crime, and in the picture her tiny face peaked out from behind a grown-up. She posted the image on a social platform, writing of how it revealed “my young curiosity, my loss and my fear in that very moment.” The photographer, she observed, knew how to capture “the human side of people — the spirit, the emotion and the truth.” She hoped, all these years later, to connect with him.

Again, it took me a minute to spot the opening, but I soon tapped out a note to three photojournalists I know with Chicago ties. By day’s end, my childhood friend and the photographer were in touch. “Tears,” she wrote, “from his end and mine.”

Michelle Krupa is a senior news editor for CNN Digital Worldwide.