- Doing Good

- Goodness Gracious

- Pain Relievers

- Call It Human Nature

- Storylines

- The Sickness Swing

- The Sound of Sublime

- Moving Pictures

- Body Language

- A Quiet Incarnation

- Giving Upward

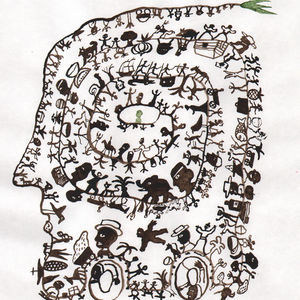

- Dauntless Luminescence

- The Shining Joy of Falling Flat on Your Face

The majority of animals who live in the deep sea — the darkest place on Earth — generate their own light. Marine creatures use bioluminescence just as humans use language: for communication, warning, manipulation, seduction, protection. There are shrimp who shoot ribbons of light to distract their predators, ostracods who string pearls of light to attract mates. At night, the bobtail squid rises to the ocean’s surface to eat, which makes it vulnerable to predators below. To blend in with the moonlight sparkling above, it relies on a symbiotic relationship with a species of bioluminescent bacteria, which generates a camouflaging light as a kind of rent.

Marine bioluminescence is produced by the same chemical reaction that makes fireflies glow. Other organisms produce light on land, too. Of the 10,000 known species of fungi, some 80 bioluminesce. On the ceilings of damp caves, glowworms congregate in the thousands, building mesmerizing sculptures of silk and shiny droplets that reflect their bodily light and attract prey. The spectacle is spellbinding, even when mediated by a laptop screen. It’s like the night sky has jumped to life. In the dark, on the ceiling, hundreds of glowworm lights blink and wobble, radiating an otherworldly blue, glittering down strings of silk that hang like necklaces from the rocks. It is easy to feel a kinship with any moth ensnared by the splendor, but I also feel admiration for the glowworms: What a stunning way to eat.

Researchers have employed a different kind of reaction known to light up the ocean — biofluorescence — to track viruses and cancer cells in the human body. A team at Massachusetts Institute of Technology is using fluorescent proteins to illuminate neurons, creating a three-dimensional map of another dark and poorly understood place: the human brain.

Elsewhere, scientists are trying to engineer bioluminescent trees that would light up cities without electricity. You can purchase bioluminescent ice cream for $220 a scoop.

My obsession with this kind of light — bizarre light, implausible light — began last spring, as our world plunged into a dark place of its own. I became bewitched by light that generates in sunless, hostile environments. Light produced by resources I’d never heard of, through complex reactions that took hours for me to comprehend. Light that evolved from necessity, even desperation. Light that shines all the time, but is too dim to observe until everything around it becomes very, very dark.

In July, my fiancé and I were walking in downtown Los Angeles. We were just a block from his apartment when I saw it. In the golden light, something small dropped from the sky, landing on the pavement in front of us. It was a delicate, breathtaking bird: gray wings and black fanned tail, mouse gray head, black beak smaller than a piece of candy corn, dark twiggy feet, lemon yellow chest. It wasn’t moving, but its round eyes were open, and its breathing seemed normal. For a long time, we watched it, and it watched us. We loitered on the pavement, monitoring it, discussing what to do. It was a busy sidewalk — we were shielding the bird from scooters, bikes, pedestrians and dogs. What would happen if we left it there? Andrew theorized that the bird had crashed into the skyscraper above us. “Maybe he has a concussion?” Andrew guessed. “You’re supposed to give it a dark place with no noise to recover.”

Finally, we made a plan. I retrieved a shoebox from the apartment while Andrew kept watch. When I returned, the bird appeared sprightly but remained immobile. As gently as we could, wearing gloves, we transferred it into the shoebox and took it inside. To relieve the bird from the dazzling Los Angeles daylight, we partially covered the box with a lid, then placed it on a shelf and waited.

Two hours passed, and the bird didn’t make a sound. We researched a little and discovered it was probably a Western kingbird. Around sunset, we relocated the box to the balcony. Gingerly, Andrew opened the lid while I looked on in apprehension.

With the force of a firework, the bird shot out. I watched its gorgeous little body sail in perfect flight, until it landed on a palm tree some distance away.

“Did we just kidnap a perfectly healthy bird?” I laughed.

“No,” Andrew smiled, squinting into the dusk. “I think he needed some time in the dark.”

I learned that sound can transform into light: sonoluminescence. I learned about Cherenkov radiation, a dim blue glow generated when a charged particle moves faster than the speed of light. The piezoelectric effect occurs when certain materials such as ceramics and crystals are squeezed or bent, and it might explain the mysterious glowing orbs that have been spotted near train tracks in Gurdon, Arkansas, since the 1930s. Deposits of quartz crystal sit under Gurdon, and some scientists have theorized that pressure somehow creates the light aboveground.

I learned that about 250,000 years passed between the Big Bang and the birth of light as we know it. Before photons could travel freely, our universe had to expand. Also: Installing solar panels in 1.2 percent of the Sahara would meet the world’s energy demands. In Japan and Scotland, the use of blue streetlights somehow reduced crime and suicide rates. The Hope Diamond is the most valuable jewel in the world, relocating from a volcano to a temple in India, to the French monarchy, to the British monarchy, to many wealthy families, before finally landing in the Smithsonian. It is blue, said to be cursed, and once exposed to ultraviolet light it emanates a deep red glow for several minutes.

Some cacti bloom only one night a year, on or around a full moon, exposing their petals for mere hours before clenching back into secrets. Countless plants and animals are attuned to the lunar cycle; the moon affects when corals spawn, where wildebeests graze, when turtles lay their eggs and hatch from them, how badgers pee, when birds sing, when a lion is most likely to attack a human. Perhaps due to an evolutionary accident, moonlight reacts with a protein in scorpions’ skin to make them glow, which they don’t like — they become shy when they glow, preferring new moons. Barn owls reflect moonlight off their white wings to stupefy their prey.

All this staggeringly important light is reflected off rock that bears the letters TDC on its surface. The last person to walk on the moon was Eugene Cernan, and on his final mission, he wrote his daughter’s initials in the dust. He called his last trip to the moon “the brightest moment of my life.”

Recently, I moved to a new neighborhood in Los Angeles. Every afternoon, I hear two little boys jubilantly screaming each other’s names in the courtyard below my apartment. The younger one has a helium voice, a head of red curls and a love for declaring his loves: his love of pizza, his love for his friend’s mother, his love for the rats in the garden. The older one seems more boisterous and competitive, but really, he is sensitive and gentle; he starts to cry as soon as he believes he has hurt someone. Their parents supervise their playdates, helping them invent games that are compatible with six feet of distance. As far as I can tell, it’s the only time of day that each boy gets to interact with another kid, and it’s clear that the closeness of their friendship is only fortified by the distance between them. “We both won,” the younger tells the older. “We both won.”

One of the places where the Northern Lights often — and spectacularly — appear is Tromsø, Norway, a city where the sun doesn’t rise between November and January. Norwegians call this six-week period of darkness Mørketid, the Polar Night. Surprisingly, rates of seasonal depression in this part of the world are relatively low. When psychologist Kari Leibowitz traveled to Tromsø to find out how people cope so well with winter, she discovered that the explanation couldn’t be reduced to cod liver oil, candlelit restaurants, ski resorts, Christmas markets, the auroras, government policy or light lamps. Instead, her studies suggested that “mindset” was the biggest determinant of an inhabitant’s mental health throughout the Polar Night. “It dawned on me,” wrote Leibowitz, “that the baseline assumption of my original research proposal had been off: In Tromsø, the prevailing sentiment is that winter is something to be enjoyed, not something to be endured.”

Among the many religious and secular celebrations of light during the darkest months of the year, the one that captivates me most is Yalda, an Iranian tradition with roots in ancient Persia. On the winter solstice, families gather at the homes of their elders for a candlelit feast of nuts, pomegranates and watermelon. The family stays up all night and recites poetry. According to a medieval Persian document, if you cannot afford a banquet, it is sufficient to bring a flower.

When I was young, I heard a story on the news about a girl my age who was kidnapped from her bedroom window. The story sparked in the tinderbox of my imagination, rapidly swelling to a wildfire of fear. At night, I stared at my window long after I was meant to be asleep, mistaking trees for human silhouettes. Soon, I became so capsized by anxiety that I told my older brother Nick about it. Instead of teasing me, he calmly led me to every window of the house, closing and locking them as he went, then showing me how difficult they were to open. As the sun set, I trailed him through the rooms, the furniture glazed pink and orange, my fear dimming. “See?” Nick said as we reached the final window. “Impossible.” His confidence made him seem like an adult to me then, but he was a child, too.

When you can’t afford a feast, it is sufficient to bring a flower.

The meditative bliss of trimming parsley leaves from their stems. The incandescent good fortune of having someone to ask you, “What? What’s funny?” when you laugh at something across the room. Watching finches gleefully bathing in the dirt. The laugh of a friend from Notre Dame — a laugh so loud and free, it tended to gather murderous looks at the cinema, but always carbonated me with its joy. My morning walk around the neighborhood reservoir.

The loop is nothing but a dirt path with a chain-link fence on one side and traffic on the other, but this walk is the best part of my day. I watch Dalmatians euphorically greeting each other, spot the pocket gophers peeping their little heads out of their tunnels, listen to Juliet Stevenson brilliantly performing George Eliot’s Middlemarch for 36 hours, read messages that people have tied to the fence with fabric.

When I am looking for a flower to bring to the banquet, I think of a friend in Los Angeles who has taken to hiding in her husband’s home office and scaring him when he least expects it. I remember a toddler I babysat in Brooklyn, how she’d drag the dog’s bed to her room every night so the dog would sleep beside her. How sweetly the dog obliged. I think of the volunteers I saw distributing chilled water bottles to people without shelter during a heat wave.

After months of drought and wildfire, it finally rained in Los Angeles. The next morning, I walked outside and inhaled the scent of quenched earth until the beauty of it brought me to tears. In the ’60s, a pair of Australian scientists invented a word for this fragrance: petrichor, from the Greek petros, or “stone,” and ichor, or “fluid that flows in the veins of the gods.” During dry spells, plants secrete oils that accumulate and break down in the ground. Rain draws the resulting bouquet of molecules — including geosmin, a common ingredient in perfumes — into the air. The enchanting smell most of us associate with rain is dependent on drought.

I’m starting to believe that darkness is the most essential ally of goodness: It alone has the power to reveal the tiny, faint lights glowing all around us, all the time. And when we can’t see any, it compels us to generate our own.

The human body emits light, strongest in the afternoon and around the lower part of the face. Human bioluminescence is allegedly 1,000 times weaker than the human eye can detect, but I’m certain I’ve seen people glow.

Tess Gunty studied English at Notre Dame, where she won the Ernest Sandeen Award for her poetry collection. She holds an MFA in fiction writing from NYU and recently worked as a research and writing assistant to Jonathan Safran Foer on We Are the Weather, a book of creative nonfiction about the climate crisis.