To Notre Dame students and employees in the early ’60s, it must have seemed like an alien spaceship had landed in the vacant fields east of the campus power plant.

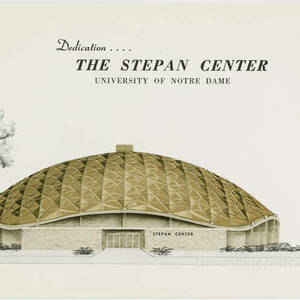

Stepan Center, its golden convex roof gleaming in the sunshine, opened its doors 60 years ago: on May 11, 1962. The geodesic dome was dedicated at an evening ceremony during the Senior Ball taking place inside the new facility.

Stepan Center was a Space Age marvel when it was constructed, with an appearance more akin to The Jetsons (which would premiere four months later) than a typical staid college building of the era.

With its brick base, gold-anodized aluminum dome and silver ceiling (reminiscent of a Jiffy Pop Popcorn pan, invented in 1958), it was like nothing seen before on campus or by most Americans.

The $350,000 facility was a gift from Alfred C. Stepan Jr. and his wife, Mary Louise, of Winnetka, Illinois. Stepan, a 1931 Notre Dame graduate, was president of Stepan Chemical Company of Northfield, Illinois.

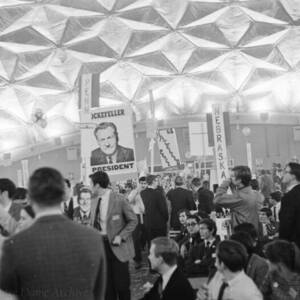

Over the years, Stepan has been the campus spot for a long list of famous speakers and landmark events. It’s hosted rock concerts, pep rallies, national political figures, the campus mock political conventions, the Sophomore Literary Festival and the Collegiate Jazz Festival.

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke in Stepan Center on October 18, 1963. A few weeks later, it was the site of a solemn Requiem Mass honoring slain President John F. Kennedy. Thousands thronged within its circular walls to hear a presidential campaign speech by Robert F. Kennedy in April 1968, two months before he was assassinated.

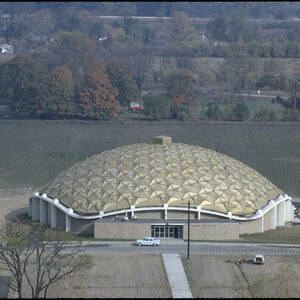

Stepan was the first building completed on what Notre Dame administrators were calling the new “East Campus.” Also under construction at that time: the new 14-story campus library, a campus computing and mathematics building, and the radiation research facility.

“The East Campus springs into view like an academic Disneyland,” the Notre Dame Alumnus declared in December 1962.

Stepan replaced the Navy Drill Hall (built in 1943 for the naval V-7 Program training Navy officers for service in World War II and used for large campus events), which was demolished to make way for the new library.

Like many 60-year-olds, Stepan’s golden crown of youth — its roof — has faded to gray. However, its campus mission as a flexible-use space is still going strong.

Stepan Center was one of the first geodesic domes built in the United States. The dome, configured in the shape of a geodesic polyhedron, consists of a lattice-work shell of triangular elements that distribute the structural stress, enabling it to withstand very heavy loads.

The campus project was announced in November 1961 and completed six months later. Circular in shape and 160 feet in diameter, the new facility was designed with a seating capacity of 3,000.

Stepan’s dome consisted of 600 sections of aluminum that were bolted together, allowing the 127-ton roof to be lifted into place as a unit, according to news reports from the time.

Invention of the geodesic dome is often credited to American designer and inventor R. Buckminster Fuller, who coined the name and popularized the form.

However, the first such dome was designed a century ago by Walter Bauersfeld, a German engineer, for a planetarium in Jena, Germany. After construction of a small dome, a larger one dubbed “The Wonder of Jena” opened in 1926. (It still stands.)

Fuller dabbled with the dome design in experiments in the late 1940s at Black Mountain College in North Carolina and received a U.S. patent for the form in 1954. The oldest surviving dome built by Fuller, from 1953, is in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. That long vacant dome, a former restaurant, still exists and is part of a planned redevelopment project.

The architectural form burst onto the international stage when a Fuller-designed geodesic dome was erected for the American National Exhibition in Moscow in 1959, during the Cold War. The exhibition displayed American art, fashion and technology in futuristic-looking pavilions.

Time magazine described the structure as resembling “a giant, gilded armadillo shell.”

“The Russians are particularly fascinated by the aluminum gold-anodized geodesic dome — 200 feet across and 78 feet high — resembling a huge bright umbrella,” read one newspaper report.

The advantages of the form were touted: its strength, flexible interior space and low maintenance costs because the aluminum doesn’t rust or require painting. No center post or other interior beams are needed to support the roof.

Fuller also developed the Dymaxion house, a futuristic single-family dwelling that was intended to be mass produced and easily shipped anywhere in the world. Looking like a close relative of the Airstream travel trailer, the Dymaxion was designed to be strong, lightweight and economical. An example of the Dymaxion house is on permanent exhibit at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. (It’s worth a visit.)

Fuller was not directly involved in the design or construction of Stepan Center. The credited architect was Minnesota-based Ellerbe Associates, the firm that handled most Notre Dame architectural projects in that era.

The list of those who have addressed crowds in Stepan reads like a “Who’s Who” of 20th century notables: William F. Buckley, Bill Clinton, Betty Shabazz, George H.W. Bush, Norman Mailer, Dick Gregory, Oliver Stone, George McGovern, Ralph Nader, Leonard Nimoy, Jimmy Carter and others.

Rock bands and other musicians who have performed there include: Peter, Paul and Mary, the Kingston Trio, The Supremes, Ray Charles, Neil Diamond, Herbie Hancock, Pure Prairie League, Indigo Girls, Wilco, Goo Goo Dolls, and many more.

In 1984, a bust of Knute Rockne that had been pilfered from the Rockne Memorial building mysteriously reappeared amid a raucous pep rally in Stepan Center, handed up on stage to head football coach Gerry Faust.

In its early decades, Stepan often was rented to South Bend-area organizations for community events such as home and garden shows, auto shows, Boy Scout dinners and science fairs.

That’s rare these days. “We don’t rent Stepan to (non-ND) organizations much because it’s so often in use by student groups,” says Kat Van Vleet ’02, the assistant director of Student Activities who manages Stepan Center.

Stepan today is the scene of residence hall dances, lectures, departmental exams, concerts, robotic football competitions, the annual Keenan Revue, campus flu shot clinics and many other events. A few weeks ago, flashing colored lights were being tested inside for an upcoming hip-hop dance competition.

During the 2021-2022 academic year, Stepan had about 480 bookings. (A booking can mean an event, an event setup or a rehearsal.)

The University has more requests for use of Stepan than it can accommodate. “We’ve had people want to fly drones inside, which we don’t allow. It’s too easy to damage the ceiling,” Van Vleet says.

The center’s midcentury modern aesthetic attracts devotees. For several years, Stepan had its own good-humored Twitter account, @StepanND, poking fun at itself and other facilities on campus.

Over the decades, geodesic domes proliferated for both commercial and residential uses. Stepan Center has a virtual twin in the Gold Dome, a bank building constructed in 1958 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, the geodesic dome resurfaced in the form of small plastic igloos used as outdoor dining space for restaurant patrons.

“Given all of its use, Stepan’s in pretty good shape,” says Doug Marsh ’82, Notre Dame’s vice president for facilities design and operations and university architect.

The University in recent years has invested in Stepan repairs and upgrades, cleaning the brick, caulking some roof leaks and replacing the original opaque windows with clear glass to provide natural light inside. The campus landmark is in good shape as it enters its seventh decade.

Stepan has lived up to the geodesic dome’s original promise of flexible, efficient activity space.

“It really costs very little to keep it going,” Marsh says.

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine. Reach her at mfosmoe@nd.edu or @MFosmoe.