Photography by Matt Cashore ’94

Photography by Matt Cashore ’94

Editor’s Note: This is part of a Notre Dame Magazine series documenting the move from the Snite Museum to the new Raclin Murphy Museum.

- Snite Moves

- Packed Schedule

- Moving Works of Art

- Museum Pieces

- Divine Inspiration

- Raclin Murphy Readies for Its Debut

Preparing to open a new museum is like putting together a jigsaw puzzle with a million pieces. Every little piece has to find its place before the job is done.

It’s late July and the puzzle that is the future Raclin Murphy Museum of Art, scheduled to open to the public in November, is halfway there.

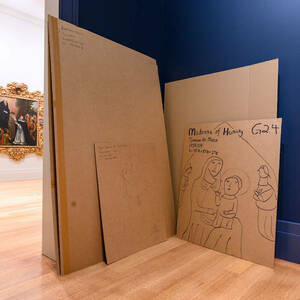

Some paintings are hanging in their designated places on gallery walls. Cardboard rectangles serve as placeholders for furniture and artworks still to come. The ceramics and indigenous pieces are awaiting the arrival of cabinets before they can be placed.

Many of the works already hanging will be familiar to longtime visitors to the former Snite Museum, which permanently closed in April. But some of the works are fresh — new to the collection, just out of long-term storage or never before viewed on campus.

“Some of the art hasn’t been on display in decades,” says Joseph A. Becherer, the museum’s director. Many artworks have undergone conservation or professional cleaning before being moved to their new home.

Planning the layout of each gallery is an art in itself. Large and eye-grabbing works are placed strategically at certain points, to draw visitors into the next room within a gallery.

Raclin Murphy Museum will serve as another cornerstone in the University’s arts gateway near the south edge of campus. A visitor standing outside the building can see DeBartolo Performing Art Center to the northwest, Walsh Family Hall of Architecture to the north and O’Neill Hall of Music to the northeast.

The museum is named in honor of Ernestine Raclin and her daughter and son-in-law, Carmi and Christopher Murphy ’68, all of South Bend, who provided a leading gift toward its construction. A lifelong friend of the University and a Notre Dame trustee, Raclin died July 13 at age 95.

Several pieces of outdoor art recently were moved into place just east and north of the museum, including George Rickey’s “Two Open Triangles Up Gyratory” kinetic sculpture; “Hot Field Flat,” by Sir Anthony Caro; and “UPBEAT,” by Clement Meadmore.

Those works are part of the Charles B. Hayes Family Sculpture Park, with meandering pathways, a pond, and native plants and grasses. The museum sits on the western edge of the sculpture park. Most of the park remains open to the public while work proceeds inside the museum.

Becherer is constantly mindful of the fact that the days are ticking by on the way to the museum’s dedication in late October. (The public opening is slated for December 1, 2 and 3.) “The greatest challenge is to simply stay on track but also to be flexible,” he says. A delayed delivery of some display furniture means more time now to hang paintings, for example.

“Anytime you do a major project like this, if something doesn’t fit, you can’t stop,” the director says. “You have to figure out another way.”

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine. She can be reached at mfosmoe@nd.edu or @mfosmoe.