Photo by Barbara Johnston

Photo by Barbara Johnston

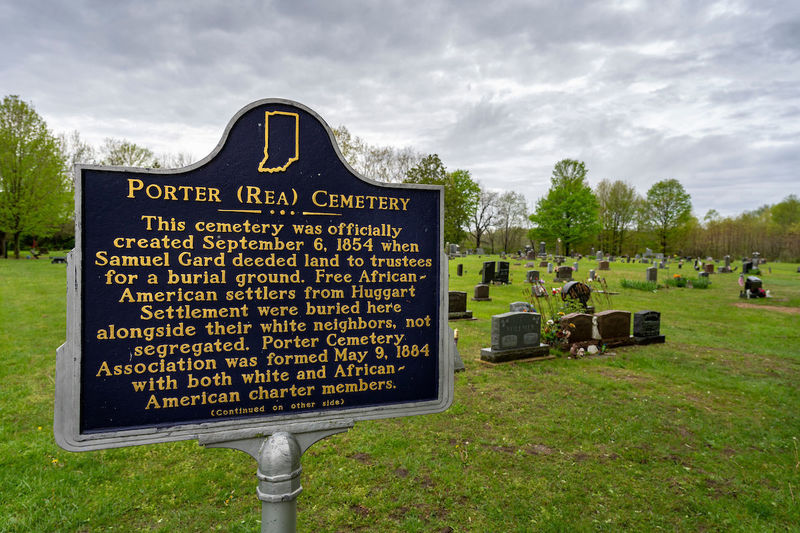

My daughter Mary and I stand at a vacant gravesite in Porter Rea Cemetery, 15 miles southwest of South Bend. Porter Rea is a small, historical cemetery within the boundaries of Potato Creek State Park. Mary is home for a week following a semester of study in Germany. We’ve come to the park to hike — a mutual love — and talk. I ask if she wants to see the plots where her mom and I will be buried someday, side by side. She does, but wonders why we bought plots here. Not here at Porter Rea, but in the flatlands of northern Indiana. Do we plan to live in South Bend after we retire, for the rest of our lives?

We do. This surprises her a little, as it once surprised me. I grew up among the mountains and valleys of Nevada and Utah, with mountain landscapes and vistas as far as the eye could see — sometimes 60 or 70 miles, maybe more. My wife, Elizabeth, and I lived in the Appalachian Mountains of western Maryland, where we could look out over hill after rolling hill, entranced by the deep green of millions of trees. We’ve lived in the Black Hills of South Dakota and marveled at the deep rocky canyons, the spreading plains to the east, and the rugged bluffs and buttes of eastern Wyoming.

We thought we’d move away from South Bend after I retired from Notre Dame: perhaps to the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia or the Black Hills. I long for wide open spaces, limitless horizons and back country roads twisting through mile after mile of uninhabited or barely inhabited land. I miss the endless variety and fascination of land formations: rock outcroppings, gorges, contorted hills and rugged mountains. And pure blue sky. The memory of such places is a memento transcendi, a reminder of transcendence. Ah, to live and explore the land in such vast spaces: What a spiritual joy it was in my youth, and would be again in my old age!

In such places I am at home.

After 24 years in South Bend, I still don’t feel at home. Not really. Why, then, have I changed my mind about staying put? Do I really want to spend eternity in a gray, cloud-covered flatland? Flat mostly (there are slight undulations in the land). And gray much of the year, anyway. South Bend is near the southern tip of Lake Michigan. Moisture and haze drift in from the lake from November through March, filling the entire sky with a dismal homogeneity that conceals transcendence and depresses the spirit. Students at Notre Dame refer to this phenomenon as “permacloud,” or “permagray” — apt word coinages. I have to use a mood light to get through the dreary winter months.

Did you know that the city of South Bend straddles the North-South Continental Divide? Did you know that there even is a North-South divide?

Why did we settle for this place to live out our lives and be buried? One reason only: family. Three of our children and three grandchildren live here, and we want to be near them, above all other desires. Ours isn’t a large extended family — our own siblings, nieces and nephews are strewn from coast to coast. We are, as parents and grandparents, an anchor for our family, and our home a place of stability in a stressful and disconcerting world. Depending on the situation, we’re either the Plan A or Plan B backup for the grandkids. We want to be near them, spend time with them, watch them grow even as we watch our children grow into mature adults. They, in turn, anchor us as we age. That’s reason enough for us to remain in this almost-flat landscape.

Are there other benefits of staying, say, consolation prizes?

Yes. I love to explore landforms and natural history, and no place is without interesting stories. Geology is one of the most fascinating of all fields of study, one I sadly did not undertake, but have nonetheless followed from a distance for much of my life, especially through the writings of John McPhee, who has translated the language of geologists into understandable prose. His books Assembling California, Basin and Range, Rising from the Plains and In Suspect Terrain, describe the geological history, respectively, of California, the Great Basin of Nevada and Utah, the Rocky Mountains and the Appalachians. Places where solid rock has thrust — or is still thrusting — hundreds or thousands of feet into the air, where the earth stretches and collides and spews hot liquid from subterranean depths. These variegated landforms tell fascinating stories about Earth’s violent and ever-changing history — rich bounty for the fertile imagination. The geology of the American West bombards you from all sides, every day.

The Midwest has precious few rock outcroppings. Little land has been pushed up or fractured by volcanoes or the collision of tectonic plates. There is solid rock, to be sure — what geologists call the Stable Interior Craton — but it lies hundreds of feet below the surface, forming the bedrock of North America. Stable Craton. Bedrock. Sounds impressive, foundational, the anchor for a shifting continent. Yet the uniformity of the surface is not much to look at. Traveling through its corn and soybean fields grows monotonous. It does not fill you with wonder, does not lure you with a desire to explore its intricacies or learn about its abrading, exploding, shifting, rising and eroding forces over hundreds of millions of years — its deep history. You have to go in search of that, sensing that something interesting must be there.

Even McPhee could find little geological excitement in the region. In his massive, Pulitzer-prize winning Annals of the Former World, all he could squeeze from this long stretch of sameness — 1,500 miles of it — from the Rockies to eastern Ohio, fits into a 35-page postscript titled “Crossing the Craton.”

The geology and character of South Bend and environs, although they might not merit a full volume, do have some unique characteristics, even if not comparable in beauty and fascination to the rugged young American West or the venerable old Appalachians. For example, did you know that the city of South Bend straddles the North-South Continental Divide? Did you know that there even is a North-South divide? There is. The waters part here. The divide is not nearly as far-reaching as the Great Continental Divide that runs the length of the Americas, from northern Alaska, along the Rocky Mountains of Canada and America, and through the Sierra Madre of Mexico and Central America, then along the Andes of South America to the Strait of Magellan. That continental divide separates the watersheds that flow into the Pacific Ocean from those that drain into the Atlantic.

No, our divide — also referred to as the St. Lawrence River Divide — is not so extensive. It begins at the “Hill of Three Waters” near Hibbing, Minnesota. Waters east of the divide, from Eastern Minnesota, East-Central Wisconsin, Northeastern Illinois, and then through northern Indiana, Ohio and New York, flow into the Great Lakes; thence into the St. Lawrence River, and finally the North Atlantic Ocean near Nova Scotia. It divides the city of South Bend, whose major river, the St. Joseph, empties into southeastern Lake Michigan, and belongs to the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River watershed, north of the divide.

The St. Joe, as the river is called locally, begins in south-central Michigan and flows southwestward into Indiana. Smack dab in the middle of South Bend, it makes a long northward turn. This curve, or bend, at the southernmost point of the river, gave the city its name.

What turned the St. Joe northward? It might have continued on its original course toward the Mississippi River watershed if not for a geoclimactic phenomenon that occurred between 12,000 and 20,000 years ago: an Ice Age. In geological time, that’s recent, not deep history, but interesting nonetheless.

Thick sheets of glacial ice carved out the Great Lakes and carried tons of rock debris with them. The lobes of several glaciers — the Wisconsin, the Huron, and the Erie — met in the general vicinity of South Bend, pushing and twisting each other around as they competed for space. When a glacier begins to melt and retreat, it drops enormous amounts of debris, sometimes enough to form hills, or at least hills as we know them in the Midwest. Geologists call that a terminal moraine. A lobe of one glacier — the Erie Ice Sheet — stopped where South Bend now is, dropping so much rock and debris that hills formed in what is now South Bend and Mishawaka, south of the river. The St. Joe met those terminal moraines and was diverted from its course enough to bend it northward.

A patchwork of deposit formations called lateral and ground moraines also mottle the region. My home in the Coquillard Woods neighborhood sits aside the loose glacial sediment geologists call till two miles north of the river. Our backyard rises about 5 feet vertically over a gradual, 20-foot incline, enough of a hummock that our children, when very young, could sled down it on a toboggan.

A few miles west of the St. Joe River, still in South Bend, are the headwaters of the Kankakee River, and they flow south of the St. Lawrence divide. The Kankakee is the heart of what was once the Grand Kankakee Marsh, one of the largest wetlands in the United States, second in size only to the Everglades.

You may have been near the Kankakee’s headwaters, even if you never heard of the river itself. If you drive two blocks past the original Bruno’s Pizza on Prairie Avenue — for decades a favorite hangout of Notre Dame students — and look north onto a vast cornfield, that’s where the river begins. Somewhere in that field. The South Bend Ethanol plant sits in the field, too. Standing there, you wouldn’t know you’re looking at a continental divide. No hills, ridges or rises are apparent enough to distinguish it. You can see downtown South Bend two or three flat miles away. The St. Joe lies on the other side of it. The land seems level. And yet, the waters part here. During the 18th and 19th centuries, traders portaged goods across land between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River watersheds, back and forth between the Kankakee and St. Joe.

I drive out to the cornfield along Mayflower Road, just north of Prairie Avenue, to see if I can find exactly where the Kankakee begins. Does it flow out of the ground at a specific spot, such as a spring, pond or lake, or does the water seep from a broad swath of swampy land, gathering eventually into channels? I see a line of stunted trees and brush running perpendicular to, then under, the road, and guess it’s a stream. It is. Before crossing over it, I stop to read a faded sign. “Dixon West Place Ditch,” it reads, and in smaller letters, “A Resource Worth Protecting,” followed by the website for the Michiana Stormwater Partnership, an association dedicated to conserving the waterways and wetlands of St. Joseph and surrounding counties.

I park my car on the shoulder. There’s no obvious place to access the field or ditch — it’s private land, and gates block all roads into it. I step over the guardrail, anyway, into the tall grasses, and descend to the edge of the ditch, which is about six feet deep. Both sides are thick with grass. The water is shallow, maybe six inches deep, but has a strong flow through a straight channel. Was this once part of the Kankakee? I follow it upstream about 70 yards, eastward toward South Bend. It then makes an unnatural, 90-degree turn north. It goes on and on, in the general direction of the ethanol plant. I’m not prepared to go further, though. I’m already encroaching on private property, and am getting close to someone’s backyard. I don’t know this area or its people, so I turn back.

At home, I check online for information about the Dixon West Place Ditch. (Such an uncomely name!) An old South Bend Tribune article notes divergent theories as to the Kankakee’s source. One says it’s the pond near the ethanol plant; another a ditch near the Byers softball fields; yet another says Beck’s Lake in LaSalle Park, all nearby. Probably no one knows for certain — the river has been so channelized and piped and covered over.

I research hydrology maps and discover that the vast cornfield has ditches scattered throughout it, and they all seem to connect with the Dixon ditch. Numerous places could claim to be the “headwaters,” so the title will have to remain between quotation marks. In truth, the entire saturated, swampy land is headwater, with water rising from the ground everywhere, then gathering in small channels. Only pumps keep the water from flooding the fields and returning it to marsh, by piping it into the ditches. Dozens of these ditches stripe the field, and one could spend days wading up them, especially during retirement, with grandkids.

To the Miami people, Kankakee means “open country, land exposed to view.” It is not what I grew up thinking of as “open country,” not in the American West, no sir. Even so, as I enter elderhood, the concept of “open country” becomes as much spiritual as physical space. After I watched a documentary on the Grand Kankakee Marsh, Everglades of the North, its mysteries and natural history — and its taming — have haunted my subconscious mind like a ghost. In a good way, like a lure. Firsthand, up-close knowledge of its intricacies wants to rise to the surface and spread. Since my children and grandchildren are holding me here, I decide to step into and explore this ghosted world.

In 2016, the Kankakee was designated a National Water Trail, beginning at Jasinski Landing, a mile downstream from where I jumped the guardrail on Mayflower Road. That’s where you can put in to Dixon West Place Ditch with a kayak or canoe. Eventually, the ditch gets called by its real name. The Kankakee is joined by many other streams and rivers on its westward course. One of them is Potato Creek, which gives the state park encompassing Porter Rea Cemetery — where my wife and I will be buried — its name. Potato Creek begins in a swamp, flows into Worster Lake, then back out again until it joins Pine Creek and then the Kankakee. The Yellow and Iroquois rivers connect farther downstream. In east-central Illinois, the Kankakee merges with the Des Plaines to form the Illinois River. The latter is a tributary of the Mississippi, which empties into the Gulf of Mexico.

The Kankakee was called a lazy river because it flowed so slowly, wide and shallow, meandering through lowlands carved out by glaciers millennia ago, forming the Grand Kankakee Marsh. Hundreds of snake-like curves and oxbows formed a 240-mile-long river. The marsh teemed with wildlife: deer, moose, elk and bison; ducks, geese, passenger pigeons and heron; beaver, mink and otter; countless species of fish. So plentiful was the game that the marsh was once dubbed the “food pantry of Chicago,” daily supplying many of that city’s restaurants and home tables with fresh meat and fish.

The gravesites are on the west side of a slight rise in the cemetery. Snowmelt and rainwater trickle slowly from there into Worster Lake, then into Potato Creek, and onward to the Kankakee, the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico. And who knows?

Then came the land speculators and developers who saw money in that “useless” swampland, and they began to dredge and straighten the Kankakee’s course. It took decades, but eventually the Indiana portion of the river became a 90-mile ditch. The surrounding land was sold and converted to cropland. Only one 9.5 mile section of the original river in Illinois remains: between the Indiana-Illinois border and the town of Momence, where it follows its pristine course undisturbed. Small portions of the marsh in Indiana have been restored, and some wildlife species, not seen in a hundred years, have returned.

Now, let’s say you decide to retire in South Bend instead of somewhere more exciting. You could canoe or kayak down the entire Kankakee, beginning in South Bend’s Dixon Ditch, if you want, for the full 135 or so miles to the Illinois River. You can spend years doing it, in segments (if your joints and ligaments are tight, don’t try it all at once). As you paddle, you could pull over to the side of the river, fasten your craft, then go lie under woodland trees or a nearby field. Dream up at the clouds while your grandchildren play, or ponder how the world is saturated with grace, and how we cover it up, hide it and attempt to channelize it — yet it seeps through the fissures of reality and flows, seeking always its destination, which is also its source: the ocean.

Geologically, the Midwest lacks excitement: there are no rocky peaks jutting from the land to form exquisitely carved mountain ranges; no deep canyons and gorges to marvel at. Its visible history goes back only to the Ice Ages — an infant amount of time in Earth’s long saga. But you can explore the waterways and natural features of two nearby watersheds; canoe or kayak down rivers; and hike riverine woodlands. You can study engineering maps and drawings of drainage systems, pumps, canals, locks and dams. Then you can go have a look at them and find out how they work. Study the history of humankind’s encounter with and attempt to control nature (for both good and ill). The human engineering feats, too, are a marvel.

In the final chapter of my memoir, Pilgrim River, I stated my desire to be cremated when I die, and to have my ashes poured into a small creek in western Maryland, where they would flow from creek to stream to river to ocean. That desire changed when Elizabeth told me she wants us to be buried side by side. This surprised me; I hadn’t known that. We hadn’t talked about it, not in 34 years of marriage.

I have never wanted to be buried in a city cemetery. Too crowded. I’m all in with social distancing, even in death. Six months before Mary and I stood before the vacant gravesites at Porter Rea, Elizabeth and I wandered through the tiny cemetery at the end of a long hike. It was then that we decided to buy two plots, right there, and to have green burials. To let our bodies decompose into nutrients that can reenter the cycle of life, or flow to the ocean.

The gravesites are on the west side of a slight rise in the cemetery. Snowmelt and rainwater trickle slowly from there into Worster Lake, then into Potato Creek, and onward to the Kankakee, the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico. And who knows? The next ice age might scrape our remaining molecules away, further south. The North American Craton might crack and split into separate tectonic plates. What energies might then be released from the earth? Life near South Bend could get exciting in a very distant future.

In the meantime, we’ll rest in peace on the outskirts of what was once the Grand Kankakee Marsh, in glacial till, near the parting of waters into two great watersheds. It will be all right; because both great waters flow into the same ocean, and all oceans are connected, and after parting, all waters flow together as one.

Ken Garcia retired in June as associate director of Notre Dame’s Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts