Editor’s note: The 6th through 12th graders of the Robinson Shakespeare Company, part of Notre Dame’s Robinson Community Learning Center, have been invited to perform Cymbeline this summer in Stratford-upon-Avon and present a workshop at Shakespeare’s Globe in London. Notre Dame Magazine reports on their journey here.

Forest Wallace thinks the basketball rim at his house is too springy, so he uses a neighbor’s hoop to practice his shot — and his lines. He keeps his script at courtside for reference, shooting and reciting, taking a glance, shooting and reciting, taking a glance, a rote process with the dual benefit of improving his basketball mechanics and his acting chops.

When it comes to the stage, at least, 14-year-old Forest is not a practice player. An admitted procrastinator, he says he’s not the right person to ask for advice about memorizing lines. His process sounds a little like an NBA game: three quarters of idly squeaking sneakers, then a finishing flourish. He’s clutch, you’ve got to give him that.

Playing Cloten in the Robinson Shakespeare Company’s production of Cymbeline, Forest found himself pretty far behind late in the game. He had hoped for a bigger part and a better person to play.

“He’s just a terrible dude,” Forest says. His aversion to Cloten contributed to his stalling.

Director Christy Burgess finally issued an ultimatum: get your lines down, now, for the spring performances at Washington Hall or you won’t go with the ensemble to England this summer.

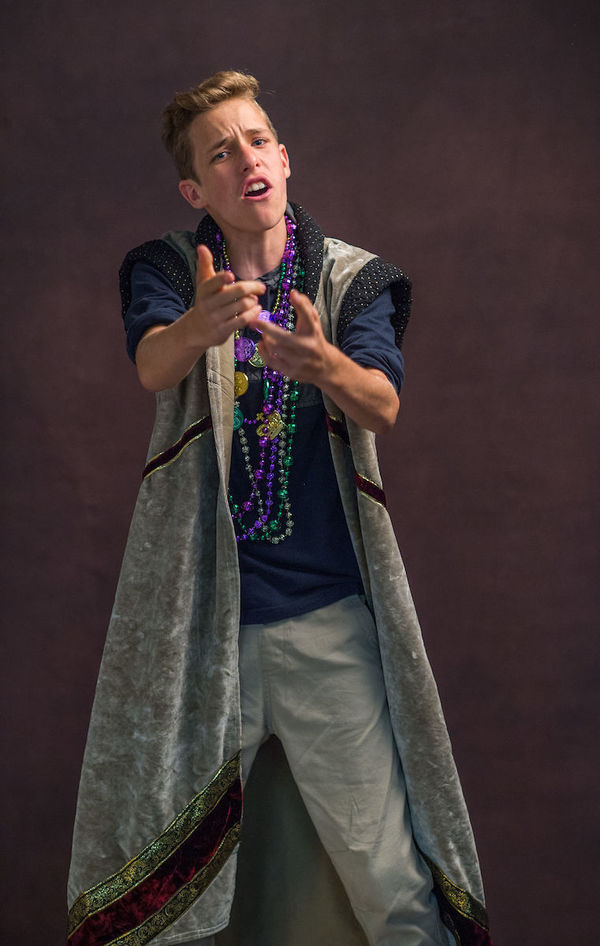

Forest Wallace embraced the insufferable qualities of his character, Cloten. Photo by Barbara Johnston.

Forest Wallace embraced the insufferable qualities of his character, Cloten. Photo by Barbara Johnston.

By that point, Forest had at least come to embrace the sitcom-villain self-regard of King Cymbeline’s loutish stepson.

“He’s a jerk, but he’s kind of funny,” Forest says. “And he’s stupid. So that's fun.”

In facial expression and body language, he delivers all the smug characteristics that make Cloten’s ultimate demise (spoiler alert: decapitation) a moment of audience satisfaction.

That’s another thing about Forest. He’s game. He’ll play the fool or the villain with enthusiastic abandon.

“Forest has this amazing unselfconsciousness about him,” Burgess says. “It’s thrilling to watch.”

His scene-stealing Cloten demands audience applause after inflicting a rap serenade on the object of his unwanted affections. He tosses the crowd Mardi Gras beads from around his neck in an act of ingratiating largesse. Even as a disembodied head, he sways and flops as if his vanquisher really is holding him up by the hair, a spoil of battle, fairly won.

Before his head rolls, though, Cloten has a lot to say for himself. And as those spring shows approached and the urgency of rehearsals increased, Forest was not well-enough acquainted with his lines. His summer trip to London and Stratford-upon-Avon was at risk. So he took his basketball and his script to his neighbor’s hoop.

He gave voice to Cloten’s injured pride:

And that she should love this fellow and refuse me!

- The Robinson Co.’s Midsummer Night’s Dream

- Undreamed Shores

- In Character

- Armored Love

- Miss Christy

- The Choreography of Love and Conflict

- Through Hoops

- As Herself

- Amusing Muses

- By Any Other Name

- Head to Toe

- My Lady Sweet, Arise

- A Cheeky Lad Grows Up

- Think on My Words

- This Magic Moment

- A Souvenir that Stays Here

- Wishes Granted

- Fetch a Turn About the Garden

- Soggy London Town

- Moved to Tears

- What Fools These Mortals Be

- The Tour of London

To his bitterness:

It would make any man cold to lose.

To his hubris:

Thou injurious thief,

Hear by my name, and tremble.

To his ironic vow:

Posthumus, thy head, which now is growing upon thy

shoulders, shall within this hour be off.

The problem with this basketball method of memorizing lines is that Forest’s neighbor likes to play, too, and he’s a distractingly funny guy. Plus it’s his hoop, so when Forest was out there that day for something like 12 hours, the neighbor finally asserted his property rights.

Desperate, Forest put up the 10 bucks in his pocket as his end of the bargain in a game to 15. If he won, he could keep the court to himself for a little while longer.

His neighbor never stood a chance. “I was playing super good,” Forest says, “because I was like, ‘I got to go to England.’”

After making the last-second shot that Burgess put in his hands, he is going to England, conveniently enough considering he’s already convinced some teachers that he’s from there. People who hear Forest speak for the first time often try to place what they perceive to be an accent.

It’s actually a speech impediment — and, once upon a time, mentioning it would have been dry kindling tossed onto the open flame of his temper. Now, if anything, he’ll play along.

There are certain advantages. When a girl asked if he was from New Zealand, he said (and it’s not at all difficult to picture Forest leaning into this particular conversation), “Yeah, I am. Have you been there?”

And he had those teachers believing he was from Birmingham, England. “It’s fun to mess with people about it.”

He’s been in and out of speech therapy since preschool, but it’s never hindered his Shakespeare performances, which he’s done almost as long.

As little kids, Forest and his twin sister had shared birthday parties where each picked a theme. In first grade, it was the Beach Boys meets Shakespeare. The music and decorations were vintage “Surfin’ USA,” combined with custom Shakespearean Mad Libs and rented costumes. Forest was Romeo.

“I only picked Romeo because he had the most lines,” Forest says, “which I guess I haven't changed that much.”

In a way, not much has changed since Burgess first got to know him as a 7-year-old in ShakeScenes, the annual Shakespeare at Notre Dame summer youth production. He was playing Petruchio in a scene from Taming of the Shrew.

Burgess had to meet with him over lunch to work on his lines but, she says, “he ended up pulling through.”

To this day, Burgess still prods Forest to spend more time with his script. And she still puts the ball in his hands with confidence when the game’s on the line.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.