Illustration by Brett Affrunti

Illustration by Brett Affrunti

- 8th Annual Young Alumni Essay Contest

- Schaal Prize: “The Understory," Austin Hagwood '15

- 2nd Place: “Death in Front," Stephanie DePrez '11

- 2nd Place: “Radical Lovers," Mikaela Prego '15, '17M.Ed.

- 2nd Place: “Courage to Enter the Dance," Ginny Varraveto '11

- Honorable Mention: “The Maroon Baseball Cap,” Tara Pilato ’17

- Honorable Mention: “On the Mount of Martyrs,” Natalia Yepez Frias ’19

- Honorable Mention: “Rallying,” Andrew Robinson ’17

- Honorable Mention: “Material Girl,” Kathleen Clark ’15

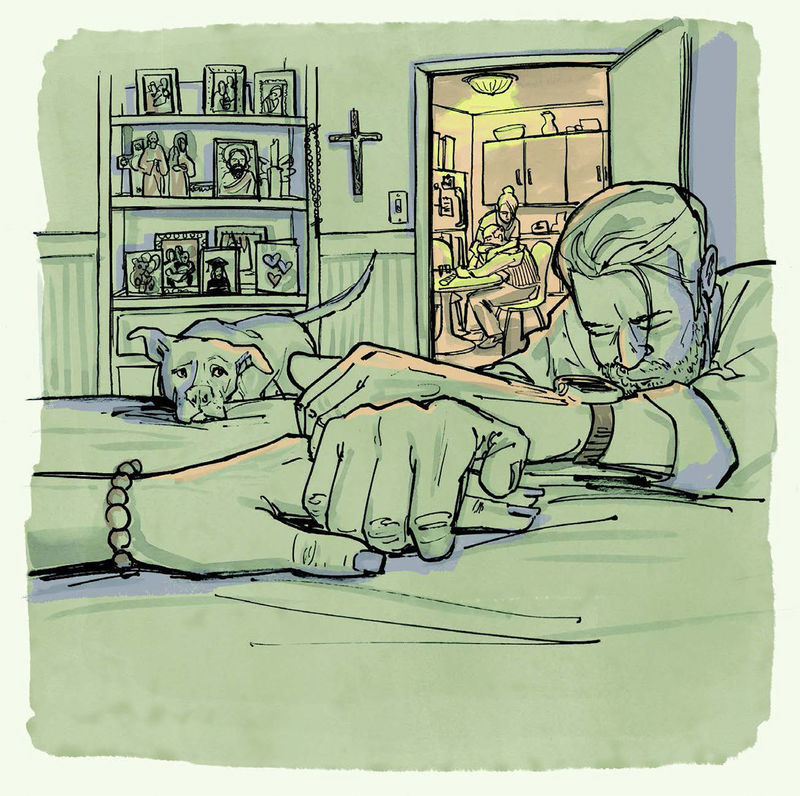

My mother died in her bed. Danny was with her, holding her, on the phone with a nurse. Ziggy was at her feet.

Within 10 minutes, family friends were there. Within another 10, my father and a priest. At the hour mark I’d made a two-hour car trip in one and walked in to find a deacon standing next to her bed, a nurse packing up pills in the kitchen and food everywhere.

Everyone got scarce so I could crawl into bed with my mother’s body, wrap my arms around her, kiss her forehead and sob like a gutted animal.

At some point we all prayed a decade of the rosary. At some point everyone left. At some point my father said, “Let’s have a final picnic,” and the three of us sat around her bed and ate sloppy Joes.

The funeral home guys arrived in suits six hours after she died. A social worker from hospice came to be present when they took her away. This hippie mama told us we’ll “see Mom in the birds and the butterflies,” and I didn’t have the heart to tell her that I will never have an iota of interest in seeing my mother in the butterflies.

This is a part of grief: making other people feel like they’ve helped you. It’s very frustrating. I want to be alone and angry but so many people “want to help” and are “reaching out.” It’s another task I must complete — being available to people being available to me. It’s a hard task. Send a letter. Don’t call. Don’t expect a text back. It’s too damn hard to be present to you trying to be present to me. I am outwardly pithy and unengaged. I am inwardly trying to refile my entire understanding of humanity, salvation, time and God.

I am angry all the time.

When they wheeled her out, we asked them to lower the gurney so Ziggy could say goodbye. He licked her face. They zipped her up. We followed her outside. Ziggy tried to jump into the van with her body. We held him on the sidewalk and watched them drive away with our mother.

People keep asking if she died at home. Of course she died at home. Where else would she die? Then I saw the death certificate: Miles of room to fill out hospital, doctor, state of care, etc. One tiny box for “Died in decedent’s home.”

I’m in the beginning stages of this business, rife with hot takes, but I cannot imagine that anyone would choose to die in a hospital when they have the chance to die at home. My mother was in her bed, with her son and dog, surrounded by family photos and every available crucifix and statue of Mary this side of the Mississippi. She had cards from Mother’s Day and her wedding anniversary and well-wishes from friends all over the country at her fingertips. She was in her favorite shirt, covered in flowers. She died as Mommy.

Her death happened at the odd intersection of gift and tragedy. Because of the pandemic, we were home. I had 36 hours to pack up my apartment in Vienna and get on the last direct flight to the United States. My brother lives in town but set up a home office in my parents’ basement. My father created an in-home studio to teach. For over a month, the four of us had three meals together every day. We made the decision to begin hospice as a family.

The pandemic brought us home, but it made my mother’s decline unavoidable. No slipping away for beers on a Friday night. No Rockies games on Sunday afternoons. No father-daughter dates to the symphony on the educator discount. No yoga, no weightlifting. I ran around my neighborhood every day, trying in vain to outrun the tears and the pounds I couldn’t stop, coming home to help Dad lift Mom from the wheelchair to the toilet, and a month later lift her up to position the diaper beneath her.

We were together for three months, roles borrowed and reversed. I stood in the kitchen at night and sobbed, yelling at my father that I’m an opera singer, not a nurse. Danny took long drives to nowhere. Dad and I told wild jokes about the funeral home that tried to show us the PowerPoint for the “Heritage Package” and the “Legacy Package.” (They didn’t get far.)

Ziggy stopped going on walks. He defied the tug of the leash and refused to go further than the driveway, then the garage, until he stopped going out the front door at all. He insisted on staying next to my mother’s bed in her new room on the ground floor — the office of a lawyer and Stanford graduate who had interned at the White House, now the epicenter of operations for the work of a body shutting down.

She died in front of us and our community. Then the house filled with people who saw her body, touched it, held her hand, kissed her forehead and beheld the flesh that held the soul that was my mother on earth, the vessel that brought my own soul into the world. The absence of the “her” in her was unavoidable. I buried my face into her neck and clung to her, like I’ve done with my mother since the moment I left her body three decades ago, and she did not hold me. She did not bring me closer and run her hand over my hair. She did not whisper “precious angel” in my ear. She was gone, and I held her emptiness. I held her and I could not hold her.

We need this: death, in front of us, in our homes, in our lives. We need to see it and feel it and hold it and know it if we can. It is awful and precious. Death at home is inescapable. It’s not a phone call or a photo or a Facebook post or a coffin or a grave. It is a body. It is the whole of human history in an instant. There is no metaphor in death; it stands for itself.

Stephanie DePrez’s essay is one of three second-place winners of the 2020 Young Alumni Essay Contest. DePrez is an opera singer, comedian and educator based in Vienna, Austria. Learn more at stephaniedeprez.com.