Editor’s note: The 6th through 12th graders of the Robinson Shakespeare Company, part of Notre Dame’s Robinson Community Learning Center, have been invited to perform Cymbeline this summer in Stratford-upon-Avon and present a workshop at Shakespeare’s Globe in London. Notre Dame Magazine reports on their journey here.

They don’t have the words in their mouths.

Cast members for the Robinson Shakespeare Company’s production of Cymbeline are reading scenes together for the first time. The vibe is loose and informal, recess meets rehearsal. Laughter and side conversations fill the large multipurpose space of Notre Dame’s Robinson Community Learning Center with the white noise of a classroom before the bell rings.

Actors sit cross-legged on the floor in a ragged semicircle around director Christy Burgess, who seems to see and hear everything. She gives them time and space for their one-liners and their playful dabbing — until she doesn’t.

Then she summons their attention and harnesses their energy with one of the Shakespearean calls-and-responses in her repertoire or a simple, “Stop talking,” projected above the din, her hand puppeting a closed mouth.

On this February school night, the students are at the start of what feels like a long journey. Their May performances at Washington Hall — let alone the late-summer trip to perform in England — seem far, far away. There’s time, or so the calendar lulls them into believing.

In front of the cast members, like hieroglyphic tablets, lie thick spiral-bound scripts. They venture preliminary impressions of characters and interpretations of the scenes to be read.

Burgess, program director for the Shakespeare Outreach Initiative, helps them tease out meanings from the brambles of Shakespearean language they’ve only just begun to clear. Most of them have been involved in this company for years, but Cymbeline and the parts they’re portraying are new.

Eighth-grader Forest Wallace plays Cloten, the insufferable frat-bro stepson of King Cymbeline. Cloten wants to marry Cymbeline’s daughter, Imogen, but Forest says his character doesn’t really love her, he’s just angling to be heir to the throne.

“He’s kind of a creep,” Forest says, and Burgess agrees, commiserating with the challenge of bringing a glimmer of humanity to an unlikeable character.

She guides more than directs, as if leading a dance. Characters and scenes develop in the direction Burgess intends but in tandem with the actors and with the opportunity, even the expectation, for the students to create within the parameters she’s defined.

“How mad does he get?” Forest asks of Cloten’s reaction after Imogen rebuffs him with poison-tipped politeness. “Is he just throwing a baby tantrum, or does he get really, really mad?”

“What am I going to tell you?” Burgess responds.

“Find it.”

- The Robinson Co.’s Midsummer Night’s Dream

- Undreamed Shores

- In Character

- Armored Love

- Miss Christy

- The Choreography of Love and Conflict

- Through Hoops

- As Herself

- Amusing Muses

- By Any Other Name

- Head to Toe

- My Lady Sweet, Arise

- A Cheeky Lad Grows Up

- Think on My Words

- This Magic Moment

- A Souvenir that Stays Here

- Wishes Granted

- Fetch a Turn About the Garden

- Soggy London Town

- Moved to Tears

- What Fools These Mortals Be

- The Tour of London

“That’s exactly what I’m going to tell you. Find it. I’m not going to give you that answer right now. We’re going to explore it and see.”

Precious Parker, a high school sophomore, plays Imogen. In this scene, with the true love of her life just banished to Rome, Imogen is forlorn and simmering with fury toward the cloying Cloten. The feeling builds until her gracious restraint cracks into spilled invective.

When Imogen declares to Cloten, “I care not for you,” Burgess wants her tongue to be the point of a spear. In this initial read through, Precious glosses over the line, the impact dulled.

Burgess stops the recitation. “Have you read this before?”

“No,” Precious says. “We went through it, but I didn’t —”

“Girrrl! You have a big part, why are you not doing the homework?”

“I —”

“No, no, it’s more of a rhetorical question. Especially since you had time today, right?”

“We did go through it, but —”

Burgess pre-empts the explanation.

“You know what I’m saying, right? Look at me!”

Precious lifts her eyelids in supplication. “Yes.”

“Yesssss,” Burgess says, the word dissolving into a sigh. “You can act and you can say it dramatically, but it’s different from knowing what you’re saying.”

This will be a recurring theme, at one time or another applicable to almost everyone in the cast. Precious absorbs the first lesson — and the subsequent air hug.

“Girrrl,” Burgess says, affection muffling the severity in her voice, “who I love.” Her arm extends like she’s tossing a ball. “And I’m throwing imaginary cotton balls at.”

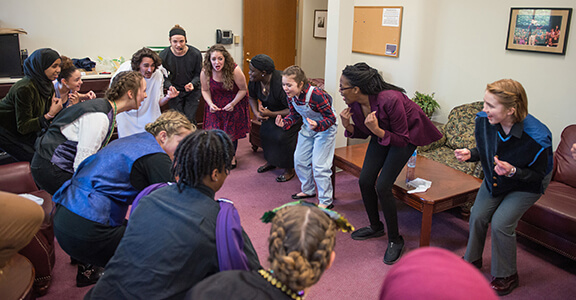

As rehearsal ends, Burgess expands the circle of exhortation to include everyone.

“Do not wait until you come here for the first time to read this through,” she says. “Get the words in your mouth. What do I mean by that?”

Responding all at once, the group sounds like radio static, but Burgess hears the right answer.

“Read it out loud. Exactly,” she says. “Because if you wait until you’re here, you’re not going to have the words in your mouth.”

They can’t afford to wait because there’s not enough rehearsal time to make up for individual work undone. For the first month, the entire ensemble meets only once a week, with smaller groups called on another day to practice specific scenes.

It adds up to a maximum of about three hours of true rehearsal each week, fleeting time that must be spent tuning the emotional register of their characters, orienting themselves on stage, sharpening the pacing of scenes. Acting, they say, starts only when lines have been memorized.

The deadline for that is April 10, the Monday after their spring break. By then, February’s feeling of a far-off show has vanished. The click-click-click up the roller coaster nears its peak and their stomachs begin to sense the swift, twisty descent to come.

The agenda for April 10 includes what’s called a “Stumble Through,” the first uninterrupted stab at performing. No scripts. No directorial input about motivations or deliveries. Just . . . go.

Burgess doesn’t attend, thinking it better to free the actors’ minds from the distraction of her scrutiny. Elliott Lorenc and Joe Russo, two of the company’s AmeriCorps members, keep detailed notes.

There’s a theoretical procedure — when the actors lose their place, they’re supposed to say “Line,” in character, to maintain the integrity of the scene — but, in practice, each of them has their own approach.

Forest often starts with a place-holding ‘Uh . . .,” his eyes aloft in search of the words. Precious pauses and sways, waving her hand as if trying to summon the lines.

Occasionally a gaze into the middle distance settles over Ophelia Emmons, playing Imogen’s banished husband, Posthumus. With reluctance, she expels the word “line” like a breath, picks up her cue from Russo and continues.

Kennedi Bridges, as the scheming Iachimo, struggles through one scene so much that, at her exit, she slides her script off a nearby table and shuffles out of the room with more dejection than anything her character experiences. She carries the script into her next scene but seldom has to consult it, as though it transmitted her lines through touch, including the moment Iachimo asks himself, “Why should I write this down that’s riveted, screwed to my memory?”

The cast’s collective effort lurches between smooth flow and uncomfortable silences — too much of the latter, not enough of the former. As a group, they’re still maybe two weeks from the point when true acting can begin.

“That’s two weeks that we’re not going to have because you still have to learn your lines,” Lorenc tells them afterward. “So, it’s not a good place.”

In each subsequent rehearsal on the exhilarating and nauseating roller coaster ride toward showtime, Burgess alternately comforts and challenges. She coaxes the actors toward more depth of emotional range after tentative first steps into the shallow end.

During the final scene, Ophelia’s wronged Posthumus encounters Iachimo, the “Italian fiend” responsible for what he believes to be his beloved wife’s death. Burgess wants “righteous anger” from Posthumus. What she hears sounds more like, “I’m going to write you a very sternly worded email. And you think about your actions,” Burgess says. “No! You could, like, tear him apart with your hands.”

Ophelia nods, inhales, starts over. Burgess provides a running commentary, like she’s conducting. First, a trumpet blast.

“Ay, so thou dost, Italian fiend! . . .”

“Yes!”

Then Posthumus turns the monologue’s artillery toward himself, requiring Ophelia to play it in a different key but without muting the force of the words.

“O, give me cord, or knife, or poison . . .”

Burgess snaps her fingers. “No, don’t lose it! Keep going! Now!”

Momentum builds until Ophelia’s Posthumus chokes out the aching cry of a ransacked soul. “My queen, my life, my wife! O Imogen, Imogen, Imogen!”

A spontaneous cheer erupts from the ensemble and Burgess asks, “How did that feel?”

Ophelia exhales. “Good.”

“Right?”

Similar moments of revelation grace almost every rehearsal, but the whole comes together in staggered fragments. Four days before the Washington Hall performance, the cast gathers at the Robinson Center for a “speed through,” which is exactly what it sounds like. Cymbeline, set on fast forward.

When they’re not in a scene, the actors scatter to tables at either end of the room, some by themselves, some in groups, poring over their scripts like students cramming for finals. Often during scenes they still have to rifle their memories for forgotten lines. Fast forward freezes on pause. When one actor reaches for a script while performing, Burgess, “embarrassed” that it has come to this, cuts the exercise short.

“It’s like a moving train, and every time that happens it just grinds to a halt. The acting stops. The action stops. Right?” she says. “And it’s not fair to the people who have worked their butts off to learn their lines.”

At T-minus three days, as they meet for their first rehearsal at Washington Hall, the cast still has not completed a full run through. Not quite tonight either, as Cameron Pierce’s Cymbeline, a forceful presence throughout the play, hits a mental wall during the last scene that prompts Burgess to shut it down.

She tells the cast to take a seat and offers rapid-fire notes in the few moments before their rides arrive. More energy overall. More projection to fill the hall. Praise for Cameron, who had such a bravura performance before her concluding lapse that Burgess matches her rehearsal-ending exasperation with enthusiasm.

“I’m so happy you are the king because you are killing it like an ax murderer,” she says. “In a good way.”

Speaking of ax murdering, the wrinkles to iron out over the final two dress rehearsals — in addition to costume tweaks, choreography for the battle dance, proper technique for stage punches and what hat Imogen should wear when she disguises herself as a man — include how to display the decapitated Cloten’s severed head. (The solution gets big laughs.)

With so little time left, everyone seems to snap into a more synchronized forward motion. There are still a few recurring missteps, but the actors make it through the final rehearsals with minimal glitches, and Burgess declares, “we have a show,” to raucous, relieved applause from the cast.

Backstage on opening night, as the clock ticks toward the call of places, frayed nerves spark into brushfires of mutual distraction. Discussions arise and recede over the relative merits of school PA announcements, old Westerns and Forrest Gump, featuring Precious reciting the movie’s famous litany of shrimps.

Some of the actors pace the hallway, reciting monologues. Others cluster together to polish dialogue. Forest practices tossing Mardi Gras beads in anticipation of Cloten’s moment of Oprah-style largesse to the audience. Sixth-grader Lizzie Graff lies flat on the floor, arms at her sides, like a hunting trophy made into a rug.

Around 10 minutes to places, Burgess gathers the cast for a high-energy round of speaking and breathing exercises, ending in a jubilant group chant. Then, with expressions of gratitude for their effort and love for her ensemble family, she leaves Cymbeline in their hands, with the words in their mouths and pride in their hearts.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.