Knute Rockne needed a plane ticket to fly to Los Angeles.

Since leading his Fighting Irish to their third undefeated and untied national championship season in his 13 years as Notre Dame’s head football coach — culminating with a 27-0 thrashing of USC in front of a crowd of 90,000 at Los Angeles Coliseum on Dec. 7, 1930 — Rockne’s offseason calendar overflowed into the first three months of 1931 with speaking engagements that took him from coast to coast.

Nobody commanded the spotlight like the Class of 1914 alumnus except Babe Ruth. When Rockne’s business manager, Christy Walsh, called with a $50,000 offer from Hollywood to work as a production consultant on the film, The Spirit of Notre Dame, the coach was scurrying for a seat.

What happened the day Rockne bumped into his friend, Father John Reynolds, CSC, on campus introduced a chapter of Chicago mob lore that surrounded one of the country’s saddest cultural episodes of the 20th century — the airplane crash that killed Rockne and seven others on March 31, 1931.

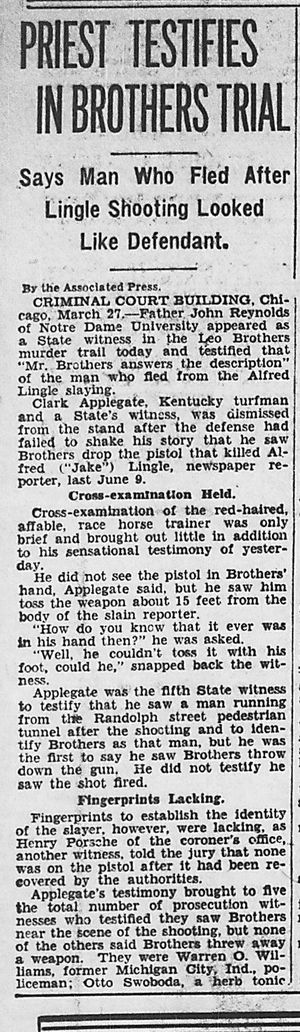

Just days before, Reynolds — a Notre Dame priest and 1917 graduate who, on June 9, 1930, witnessed the murder of Chicago Tribune reporter Jake Lingle in a downtown train station during rush hour — had testified in the trial of Leo Brothers, a member of Al Capone’s Chicago Outfit charged with Lingle’s slaying.

All along, Reynolds insisted that Brothers was not the gunman. But Chicago’s police and prosecutors needed a conviction to soothe public demand for justice in the killing of the newspaper reporter. (Lingle had moonlighted delivering payments from Capone’s Cicero headquarters to crooked politicians and judges to the tune of $60,000 a year — nearly $1 million today).

Whispers had it that Capone paid Brothers to take the fall for the actual gunman, Frankie Foster, a gangster Capone especially valued because he was loyal and ruthless. If the priest told a jury he saw Foster snatch the gun from a bumbling accomplice and fire a bullet into the back of Lingle’s head, Capone would lose one of his top hitmen to prison.

For nine months, Reynolds was a marked man. He couldn’t step outside of Morrissey Hall without watching his back.

In one instance the previous November, a strange man had approached Reynolds outside Morrissey, taken a picture of Jake Lingle out of one pocket and a photo of Leo Brothers out of the other, and asked, “Are you going to testify against this man?”

The scariest incident occurred as Reynolds waited for a train in Chicago and came face to face with Frankie Foster and six other intimidating goons. The priest noticed one of the men pull a gun from his side pocket and shift it inside his coat in full view.

“I knew I had two things going for me, two strikes on them,” Reynolds later reasoned. “One, I was a priest. Secondly, I was Irish, and if he killed an Irish priest in Chicago the whole city would turn against him.” Foster returned to the car with his men.

Two letters sent to Reynolds carried the same ominous message: Notre Dame will be more sorry than it realizes if they allow you to testify.

On Friday, March 27, the terrified priest took the witness stand. When asked to identify Brothers as the shooter, the priest replied vaguely, “He answered the description.”

The next day Reynolds was strolling across Notre Dame’s campus when he bumped into Rockne, who had returned from a family vacation in Florida to oversee the first week of spring football practice.

Father Reynolds testified right after this press photo was taken. (Courtesy of John Davenport)

Father Reynolds testified right after this press photo was taken. (Courtesy of John Davenport)

They chatted. Rockne mentioned that Universal Pictures wanted him in Hollywood, but he couldn’t find an airline reservation and there wasn’t time to travel by train to Los Angeles. Reynolds had planned to fly to Los Angeles after the trial to unwind, and he had a ticket that would take him there from Kansas City, but the trial was still ongoing and classes were about to resume, keeping the history professor in South Bend.

“Take it,” Reynolds said, handing his ticket to Rockne. The flight was set to leave from Kansas City the following Tuesday morning, putting Rockne in L.A. that night.

By the time the football coach arrived by train in Kansas City, at about 7 a.m., the Transcontinental & Western Air Fokker F-10 scheduled to fly him and five other passengers to Los Angeles was in jeopardy of being grounded. Flight mechanic E.C. “Red” Long refused to sign off on the plane’s structural safety log after finding the panels were “all loose on the wing.”

But an unknown airline supervisor pulled rank and signed the plane into service. “I don’t know who signed the plane off, but they took the airplane,” Long later told investigators from the Aeronautics Branch of the U.S. Department of Commerce.

After less than an hour in the air, trouble hit.

“First reports were that the plane exploded.” The magnitude of that single line documented on page 16 of the Commerce Department’s official investigation report into the crash of Flight 5 at 10:45 a.m. on March 31, 1931, cannot be overstated.

Newspapers across the country quoted teenager Edward Baker saying he heard the plane “explode in the air” and “spin in flames” as it crashed to the ground in a pasture on his father’s remote Kansas ranch.

“Looking up, the youth saw an airplane burst into flames and rocket toward the earth,” the Sedalia (Mo.) Democrat reported that afternoon.

Finding evidence wouldn’t be easy. By the time the lead federal investigator, Leonard Jurden, arrived in nearby Cottonwood Falls, souvenir scavengers had ravaged the crash site and hauled away significant chunks of the plane that contained vital clues.

Two days later, a coroner’s jury convened to hear testimony from witnesses and aviation experts offering circumstantial theories to determine a cause.

Investigators posited that weather moisture might have been a factor after finding the plane’s plywood outer skin bonded to the aircraft’s ribs and spars with water-based aliphatic resin glue. But the plane’s designer, Anthony Fokker, countered that theory after inspecting a small piece of the wing found on the ground. “Material and glue joints all perfect,” Fokker concluded, adding that the “pilot may have lost control on account of inexperience in blind flying.”

Airmen who had flown with the deceased pilot, Robert Fry, came to his defense. A former U.S. Marines pilot who regularly flew the route from Kansas City to Los Angeles, Fry was lauded by one former co-pilot “as one of the best blind flyers in the company.”

The coroner’s jury left the cause of the crash “undetermined.” The Department of Commerce was similarly indecisive in its report.

Not long afterward, a publishing company in Minneapolis printed a booklet that cut straight to scandal. Uncensored! Truth About Rockne’s Strange Death made its case on the cover copy (“Not a Broken Propeller . . . Not Ice on the Wing . . . At Last — Inside Story of the Fatal Crash”) and ripped the federal report’s findings as nothing more than conjecture.

“But it’s not ridiculous to consider that time after time we have had examples of sabotage, and that this might have happened to the Rockne plane,” an Army air service pilot charged in the booklet.

Uncensored! didn’t name the Kansas teenager, Edward Baker, but it affirmed his account of hearing a bomb explode in midair — an affirmation magnified two years later in shocking headlines first printed by the South Bend News-Times and circulated nationally.

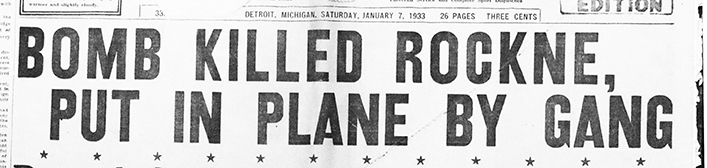

“Bomb Killed Rockne, Put in Plane by Gang,” screamed the headline atop Detroit’s Evening Times on Jan. 7, 1933, over the subhead, “Plot Bared by Secret Service . . . Timed Blast Intended for Witness to Killing Whose Ticket Noted Coach Used.”

According to the News-Times, “an unimpeachable source” had said that the Secret Service was investigating a bomb as the cause of the crash.

“The bomb . . . was intended to snuff out the life of the Rev. John Reynolds of Notre Dame University, who was a witness to the gangland execution of [Jake] Lingle,” a wire story reported.

“Father Reynolds, it was said, had booked passage to California on a Western Air Lines plane, but at the last minute he changed his plans and Rockne took his place. . . . Government operatives were in South Bend this week. . . . It was reported they were working with airline officials in the hope of getting some traces of the mobsters who were believed to have caused the plane crash.

“Father Reynolds was an important witness at the trial of Leo V. Brothers, who was convicted of the sensational Lingle slaying and was sentenced to 14 years in the state penitentiary,” the article concluded. “Credence was given to the theory that Rockne’s plane was wrecked by a bomb when it was recalled that witnesses declared a violent explosion preceded the crash.”

The Santa Ana (Calif.) Daily Register’s version of the News-Times story took the Secret Service information one step further. “Secret service operatives were in South Bend a few days ago rounding out their evidence . . . and had it complete even to the name of the man suspected of placing the bomb in a mail pouch in the plane,” the paper reported on Jan. 6.

The source did not reveal the suspect’s name.

The story died quickly, lost in news of the unfolding Depression and the ascendancy of Adolf Hitler in Germany. Public interest had shifted.

Reynolds left Notre Dame in 1939 and eventually settled in a Trappist monastery in Utah. Shortly before his death in 1986 at the age of 92, the priest gave a lengthy interview on tape to a man named Dan Karton. When questioned about the crash, Reynolds didn’t flinch.

“They bombed it,” he said. “Yeah, that is the way they got even with Notre Dame.”

“The mob rubbed out Knute Rockne because they let you testify?” Karton inquired.

“Yeah, yup, absolutely,” the priest maintained. “Oh, I am sure of that. . . . Oh, yeah.”

Jeff Harrell is an award-winning journalist who spent 10 years covering police, crime, federal courts and the mob for the Staten Island Advance. His book, Rockne of Ages, details the circumstances surrounding the plane crash that killed the legendary coach.