I am the keeper of a family memory. Its details are blurry and its edges curled, but I hold it close, like a pocketworn heirloom photograph.

My grandmother is 6. She is playing on the living room floor at her home in Kimberly, Wisconsin. Her mother is in the cellar, washing clothes, when something overcomes her. A vision of her son — a panic, a premonition — sends her rushing up the stairs, certain that her heart has broken.

“There’s something the matter with Harry!” she cries. “There’s something the matter with Harry!”

She bursts into the living room and collapses into a chair, anguished, weeping for her son Harry, some 200 miles away.

That afternoon, the parish priest knocks on the front door. The minor seminary has called him at the rectory, home to one of the few telephones in town. He is afraid he has bad news, but what he has to say comes as no surprise.

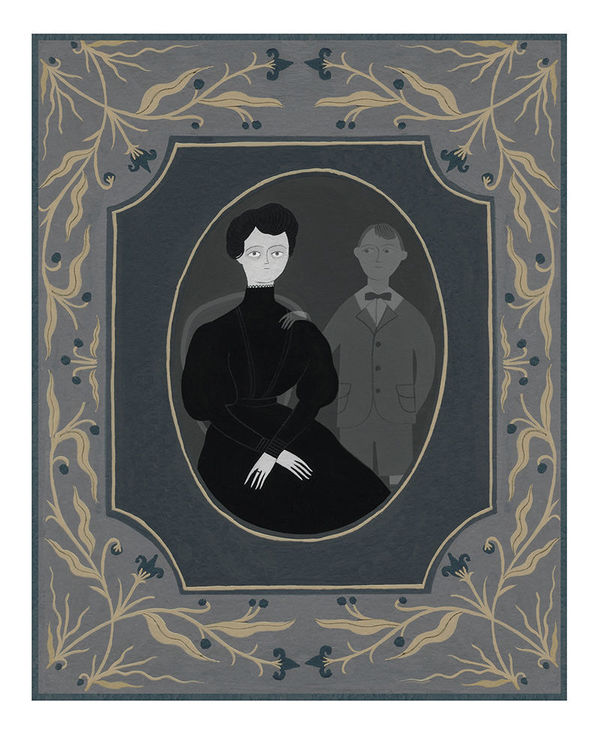

The Van Thiel children (l to r), Harry, Alberta and Jordan, in 1914.

The Van Thiel children (l to r), Harry, Alberta and Jordan, in 1914.

What happens to us when we die? Is it possible we can visit those we love? Apart from this one family remembrance and what I witness during the consecration at Mass, I have no firsthand experience of the supernatural, yet there is much about the story of my great-uncle Harry that has always rung true.

In the eighth grade I read Ambrose Bierce’s “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” the Civil War tale of a southern planter, Peyton Farquhar, who is set to hang from the very railroad bridge he’d hoped to burn down as a last, desperate defense against the advancing Union army. The rope around his neck snaps. He plummets into the water below and, as bullets and grapeshot rocket by, he strains to escape, picking his way through 30 miles of wilderness then up the garden path to the front door of his home and into his wife’s loving arms — and I will leave you to recall or imagine what happened to Peyton Farquhar at Owl Creek Bridge.

Bierce published his story in 1890, two years before the Swiss geologist Albert Heim took a break from his studies of Alpine rock and glacial formations to publish the narratives of mountain climbers, construction workers, soldiers and others who had nearly died in accidents but then revived, and six years before the French psychologist Victor Egger wrote about the expérience de mort imminente, what we call today the “near-death experience.”

Separation from the body into a realm free from the constraints of time and space. The kind welcome from otherworldly messengers, or from those who have gone before. Hyperactive senses of sight, smell and sound, and the perception of colors we’ve never seen. Preternatural awareness of things we cannot possibly otherwise know. Oceanic love, joy, warmth and oneness. A light at the end of a tunnel. The “panoramic life review.” A point of no return; a choice to go back, or to keep going.

Many have come to associate these wispy notions with New Age spirituality, butting up as they do against the cherished theological claims — or at least what we think we believe — of so many established religions. Yet there they are, notes Bruce Greyson, professor emeritus of psychiatry at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, surfacing in various forms in the Bible, the Quran, the Tibetan Book of the Dead, the folklore and art of Egypt, India, Japan, the South Pacific, Africa and the Americas. Plato, in the Republic, tells of a foot soldier who perked up on his funeral pyre to share his impressions of life after death, just another reminder in the great philosopher’s vast corpus that things are never merely what they seem.

“It is only in the last hundred years, perhaps, that fewer and fewer people truly know that life exists after the physical body dies,” the Swiss-American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross wrote in 1980. Things seem to have rebounded: Today we’re at least as afterlife-obsessed as our ancestors were in the days of Bierce, Heim and Egger. These days, proofs of heaven, whether they come from 55-year-old neurosurgeons or guileless 3-year-old boys, spend years on the bestseller list. For laughs we turn to NBC’s The Good Place, for laughter-through-tears we pull out Pixar’s Coco.

What do we 21st-century Americans think the great beyond is like? According to pollster Kathleen Weldon, more than three-quarters of us expect it to be, well, a good place. A peaceful and happy existence in which God’s love and presence will be felt and shared among souls and bodies free of blemish and any physical impairment, and where we’ll grow spiritually and live forever in the company of our family and friends.

My great-grandmother’s son, Harry Van Thiel, age 12, died on the morning of Tuesday, October 12, 1920, at a Catholic boarding school in Illinois. The illness was swift, unexpected — and cruel. A perfectly healthy child days before, Harry was one of several boys at the school killed by an outbreak of “black diphtheria,” a particularly nasty version of the throat infection that made it difficult to breathe or swallow. Within a few years, the disease would be preventable by routine vaccination.

Part of Harry’s story — the dying part, I think — is about fear. I wonder if it came to my mother’s mind that night when I was 4 or 5 and I turned up in my parents’ bedroom, unable to breathe, unable to speak or scream, and she rushed me downstairs, outside, into the cool night air that a nurse later said almost certainly saved my life. And I wonder if it explains why the Feast of St. Blaise, and its weirdly specific blessing with crossed candles to protect against diseases of the throat, occupies an outsized spot on our calendar.

Then we have the death part. Harry’s experience wasn’t a close call. It was death, period. And his mother, Mary, knew it as if she’d been sitting at his bedside.

My grandmother, the little girl playing on the living room floor, told and retold this story many times, and though she never put it this way, I think it’s about unfinished business.

Nobody dies alone, said Kübler-Ross, who devoted most of her career to the psychology of dying and death — “some 20,000 cases of people all over the world who had been declared clinically dead and who later returned to life” — and who wanted to share her findings so people wouldn’t be afraid anymore. We’ll never walk alone, she affirmed, either because we’ll be able to visit anyone we like, or because someone will be waiting for us: a guardian angel, a spirit guide, a beloved family member who’s already dead.

A woman hospitalized during wartime lost her vital signs for more than 20 minutes. Drawn toward a light, basking in sensations of unconditional love and peace, she awoke in a “green, undulating country” being approached by a group of soldiers led by her favorite cousin. They chatted, the soldiers moved on, and a voice explained that these men had permission to help the dying meet their deaths. She did not know until later that her cousin had just been killed in battle.

Illustration by Yelena Brykenkova

Illustration by Yelena Brykenkova

One girl told her father about meeting her brother on the other side. The boy had consoled her so tenderly that she hadn’t wanted to come back. Still, the encounter confused her. She knew that she had no brother. “Her father started to cry,” Kübler-Ross wrote, “and confessed that she did indeed have a brother who died three months before she was born.” Her parents had never told her.

The founder of the conservative religious journal First Things, Father Richard John Neuhaus had no use for Kübler-Ross’ famous writings on the “five stages of death,” and he was skeptical of such tales of near-death experience — until his own in 1993. Recovering from an emergency surgery to remove a colon tumor and repair his ruptured intestines, he sat up one night “jerked into an utterly lucid state of awareness” and staring at something like a bluish-purple curtain, though his body lay flat on the hospital bed.

“By the drapery were two ‘presences,’” he wrote seven years later. “I knew that I was not tied to the bed. I was able and prepared to get up and go somewhere. And then the presences — one or both of them, I do not know — spoke. This I heard clearly. Not in an ordinary way, for I cannot remember anything about the voice. But the message was beyond mistaking. ‘Everything is ready now.’”

The messengers were friendly. “They were ready to get me ready,” he explained, which for Neuhaus evoked the Catholic doctrine of purgatory. “The decision was mine as to when or whether I would take them up on the offer.”

The grace of a happy death. Could it be this awaits us, whether the dying is happy or not? Kübler-Ross wrote of multiple sclerosis patients who had danced in near-death, of blind people who could describe the colors and patterns in clothing after shucking their afflictions. Once out of their bodies, liberated from all constraints of time and space, the dead could hop planets, she said. Skip from star to star. Or, of far greater value, say their goodbyes. Those among the living who have a premonition, or a vision, like my great-grandmother, “are by nature very intuitive, for normally one doesn’t notice this kind of visitor.”

All of this happens to the near-dead, notes research psychologist Ed Kelly, Bruce Greyson’s colleague at the Virginia medical school’s Division of Perceptual Studies (DOPS), while “the conditions which neuroscientists believe are necessary for conscious experience have been abolished.” Meaning they have no brain activity. “And that,” he adds, “can be shown categorically.”

Sure there are skeptics, Greyson acknowledged two years ago at a panel celebrating the 50th anniversary of the research group’s studies of near-death experiences (NDEs) and related afterlife phenomena. Some of these skeptics say the research is subjective and retrospective, that memory is unreliable, too easily embellished and rosier with time. But in 2002, Greyson re-interviewed people who had first told their stories 20 years earlier. He found their accounts virtually unchanged.

That finding alone doesn’t establish that NDEs are real events rather than fantasies, Greyson understood. So he and his team deployed a memory characteristics questionnaire, a research tool designed to distinguish real events from imagined ones. “What we found is that for those people who had NDEs, the near-death experience was remembered with more clarity, more detail, more context and more intense feelings than real events from the same time period,” he said — and the discrepancy between that pairing was greater than the differences between their memories of the other real and imagined events they had experienced around the same time.

Try to explain away whatever had happened to these people as neurochemically induced hallucination, as the result of nerve damage or lost oxygen, as a psychological dissociation under stress, or as pure wishful thinking; for them it was “realer than real.” And there’s no data to support these other theories either, the skeptics’ skeptics point out.

“One shouldn’t try to convince other people. When they die, they will know it anyway,” Kübler-Ross liked to say.

Harder to square with the linear model of the near-death experience — the transition from life to afterlife that Kübler-Ross likens to a butterfly slipping its cocoon — is the cycle of reincarnation. That’s where DOPS got its start in 1967, in psychiatrist Ian Stevenson’s research on very young children who described memories of a past life. The 2,500 cases he and his students gathered came from all over the world, most (but far from all) found in cultures with widespread religious belief in reincarnation.

“These kids were not claiming to be Cleopatra,” said Stevenson’s protégé Jim B. Tucker, but about 70 percent of them told stories of otherwise unremarkable lives that had ended unnaturally — murders, suicides, accidents, combat deaths — with enough detail for researchers to track down real-life matches. Often a birthmark or birth defect would match the fatal wounds on the body of the deceased person. A little girl with severely deformed hands recalled the life of a murder victim whose fingers had been amputated. A boy born with a “stump” of an ear and other facial deformities told of being killed by a shotgun blast to the side of his head. The details of their complete stories, Tucker said, aligned with the documentable lives of people their families didn’t know.

The most analyzed case is James Leininger, the son of an evangelical Christian couple in Louisiana. An otherwise normal child who loved playing with toy airplanes, James at age 2 began having nightmares and would shriek, over and over, “Airplane crash on fire! Little man get out!” During playtime, he’d smash his toy plane into the wooden coffee table, leaving dents. When his parents asked about the nightmares, he said he flew a “Corsair” and had been shot down by the Japanese.

More details came out as the months went by. He’d flown off a “boat” called the “Natoma.” He drew pictures of air battles, signing them “James 3.” And when his father, Bruce, opened a book about the Battle of Iwo Jima one day, James pointed to a picture and said, “That’s where my plane was shot down.”

One pilot flying off the aircraft carrier USS Natoma Bay was killed at Iwo Jima. His name was James Huston Jr., and when interviewed in the 2000s both his elderly sister and his best friend on the ship believed little James was the man they knew, reborn to take care of “unfinished business.” Depending on whom you believe, the story of James Leininger — in his late teens and enlisted in the U.S. Navy at the time of Tucker’s 2017 presentation — is either the “gold standard” of logical errors like confirmation bias and observational selection bias, or “possibly the best documented case of reincarnation in the West.”

I don’t believe in reincarnation for a long list of reasons, but let’s stick with personal preference. Do-overs were for contentious, backyard games of war when I was a kid myself, not something I want to entertain as an attractive existential possibility.

I’m fine with there being an end, even if it comes unannounced. If life ends in a full stop with some snap of the cosmic fingers, well, that’s too bad. But is that really all there is to our story, given the visions of our prophets and the songs of our poets, given the goodness that persists in the chaos of the universe and the evils in human history? And if it is, would seven out of eight of us still believe in an afterlife?

Death doesn’t frighten me. Dying like my great-uncle Harry does, because I’m wimpy. But death does not. I choose to believe the gentlest of what we have that passes for evidence. Maybe because — for me, just as for Peyton Farquhar — anything else is too terrible to contemplate.

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine.