I will never forget the scariest ghost story I ever heard. I attended summer camp in Nova Scotia, on a crescent-shaped promontory overlooking the Bay of Fundy. Then and now, this part of the world is thinly settled. In the pine forests descending to the rocky coast, we could see only one house for miles around. Dr. Magnuson’s house.

As a nominal adult, I can assert that there never was a “Dr. Magnuson,” and that he never had a young son, William, who grabbed the family shotgun from the mantel and killed the red-uniformed Mounties sent from Digby to arrest his father. Dr. Magnuson had been accused of medical malpractice. William was hanged for his crime, but his father retrieved his beloved son’s body and used his medical black arts to bring the boy back to life.

As so often happens in stories like this — here’s looking at you, Mary Shelley — something went terribly wrong. William returned to life as Little Willy, the dwarflike werewolf with hideous fangs and a taste for the flesh of farm animals, random wildlife and young campers.

It is true, we would earnestly explain to the campers as the last campfire embers turned from red to ash-gray, that these events took place a long time ago. Dr. Magnuson may no longer be alive. As to Little Willy’s precise age and whereabouts, who can say? Did you hear about that mutilated deer carcass they found over by St. Margaret’s Bay? It’s really time for you campers to go to sleep now.

What is a ghost, you ask? Let’s go with definition 5(a) in the Oxford English Dictionary: “an incorporeal being; a spirit.” That artfully dodges the purported malevolence or beneficence of the specters, and also avoids the thornier question of whether ghosts actually exist.

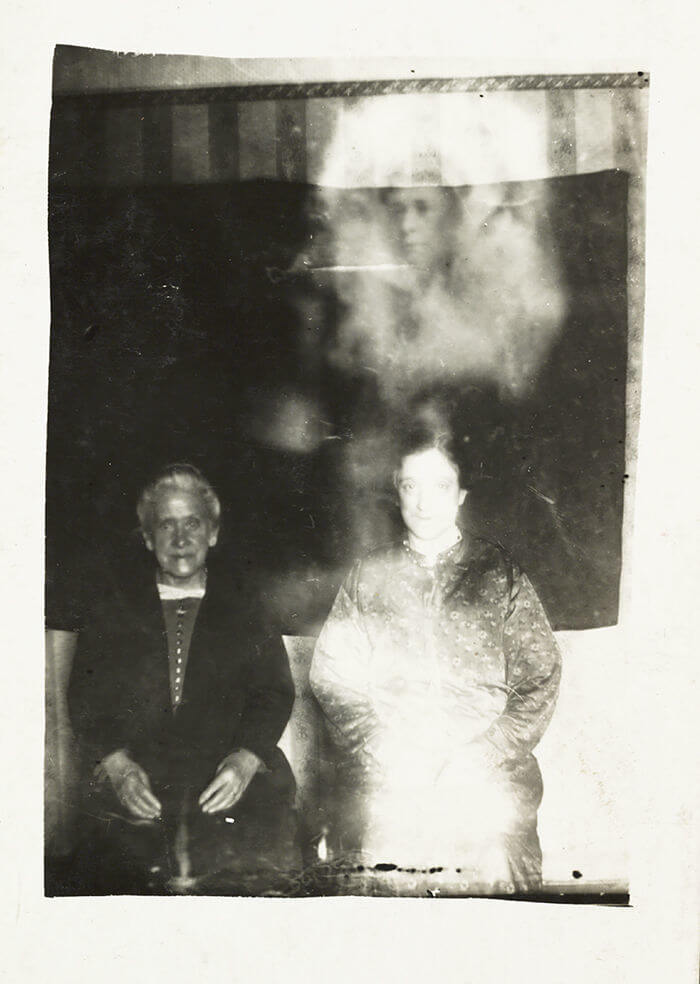

A ghostly image appears in this portrait created by William Hope about 1920. (National Media Museum Collection)

A ghostly image appears in this portrait created by William Hope about 1920. (National Media Museum Collection)

According to a 2013 Harris poll, about 42 percent of Americans believe in supernatural beings, and half don’t. If you happen to attend church, as I do, that poll’s headlined conclusions were darkly comic: “Belief in God Down, Belief in UFOs Up, Study Says.” (Ghosts were lumped in with astrology and extraterrestrials.) In a nutshell, Stephen King stock rising, New Testament stock falling.

If you do believe in ghosts, you are in excellent company. Two Nobel Prize winners, Marie and Pierre Curie, attempted to communicate with the spirit world with the help of Eusapia Palladino, a famous medium and charlatan. Thomas Edison told The American Magazine in 1920 that “I have been at work for some time building an apparatus to see if it is possible for personalities which have left this earth to communicate with us.”

Edison’s “ghost box” never saw the light of day.

Ghost stories date from forever. In Book 11 of the Odyssey, Homer sends Odysseus to the underworld to meet the ghosts of Achilles and his own mother, a scene recently memorialized in Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize lecture of all places. The Roman magistrate Pliny the Younger related a story about the philosopher Athenodorus investigating a suspiciously underpriced (because haunted) house in Athens. It turned out that the night-walking, chain-rattling ghost had been improperly buried, and its fetters badly corroded, doubtless causing much discomfort. “The bones were collected, and buried at the public expense,” we read in Pliny’s Letter to Sura, “and after the ghost was thus duly laid the house was haunted no more.”

Let’s just hand-wave William Shakespeare, who loved to freight his plays with specters and spirits. “Great Caesar’s ghost!” — an epithet made famous by Clark Kent’s newspaper boss, Perry White — references Julius Caesar, Act IV, Scene 3. The knife-wielding Brutus, who hastened Caesar’s journey to the spirit world, is predictably aghast: “Art thou some god, some angel, or some devil/That makest my blood cold and my hair to stare?” Hamlet, Macbeth and King Richard III all see ghosts in the Bard’s greatest tragedies.

The acknowledged heyday of the English-language ghost story bestrode the Victorian era, from Charles Dickens (Nancy’s ghost haunts Bill Sikes in Oliver Twist, 1838) to Henry James (The Turn of the Screw, 1898). Dickens, who tapped the incorporeal dimension whenever he needed to, as in A Christmas Carol and Bleak House, was sardonic about using ghosts in fiction. In his magazine, Household Words, he noted that ghosts are “reducible to a very few general types and classes; for ghosts have little originality, and ‘walk’ in a beaten track.” Ambrose Bierce, whose famous story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” is often included in ghost collections, likewise waxed sarcastic about visitors from the netherworld in The Devil’s Dictionary: “There is one insuperable obstacle to a belief in ghosts. A ghost never comes naked: he appears either in a winding-sheet or ‘in his habit as he lived.’”

I apologize for hand-waving more greats, such as Edgar Allan Poe, who built a career on ghost stories, and M.R. James, the provost of King’s College, Cambridge, who popularized the “antiquarian ghost story.” But I need to address pen pals and fellow phantasmascribes Henry James and Edith Wharton, avid practitioners of the ghostly arts.

Wharton, whose 11 best spooky tales appeared in the 1937 collection, Ghosts, praised good ghost stories’ “thermometric properties.” Meaning sending a chill down your spine. Her stories, which, like Henry James’, often take place in country manors, “are among the best you will ever read,” according to critic Michael Dirda. In two of Wharton’s better known stories, “Afterward” and “Kerfol,” Americans buy run-down foreign mansions “for a song.” (They should have listened to Athenodorus. These houses are underpriced for a reason! But I digress.)

It is somewhat counterintuitive that the authors of such upper-middlebrow classics as The House of Mirth and The Golden Bowl enjoyed shivering your timbers, but there you have it. The Turn of the Screw was so thermometric, James told his friend Edmund Gosse, that when he corrected the proofs, “I was so frightened that I was afraid to go upstairs to bed.”

James based Turn on a story once told him by Edward White Benson, the Archbishop of Canterbury and a member of the Cambridge Association for Spiritual Inquiry, also known as the Ghostlie Guild. The novella is a bridge between Poe’s short-form masterpieces and the full-length horror novels of our time, and its plot is simple: A governess sent to tutor an orphaned brother and sister in a stately country home starts to see the ghosts of her predecessor and a deceased manservant. Unpleasant events ensue.

Why do we return again and again to ghost stories? Why do they give us pleasure? Scary tales counterstimulate the brain, explains Margee Kerr, an Ursinus College sociologist of fear who has consulted for haunted houses around the country. “It’s all about triggering the fight-or-flight response to experience the flood of adrenaline, endorphins and dopamine, but in a completely safe space,” she told The Atlantic. “Our brain is lightning-fast at processing threat, [but it] has time to process the fact that these are not ‘real’ threats.” This is why sitting in a movie theater or around a summer campfire surrounded by friends is ideal for experiencing horror. You can feel scared and know that you are safe.

The ghost story has endured, even though Edith Wharton worried that the “ghost instinct” would succumb to modern technology. “The faculty required for [its] enjoyment has become almost atrophied in modern man,” she wrote in the introduction to her collection. “I seem to see it being gradually atrophied by those two world-wide enemies of the imagination, the wireless and the cinema.” Writer Osbert Sitwell, a member (with William Butler Yeats and Arthur Conan Doyle) of London’s Ghost Club, opined that “ghosts went out when electricity came in.”

But no.

Modern and not-so-modern technologies have adapted perfectly to the needs of contemporary ghostmeisters. My wife and I once terrorized a carful of (our own) children by playing Stephen King’s “The Mangler” on our minivan’s tape deck, back in the era of minivans and tape decks. The plot may not sound scary to you: The pressing machine, or mangle, in a commercial laundry becomes possessed, thanks in part to some nightshade and fresh blood. Take my word for it, it’s terrifying. Happily our children were listening in the proverbial “safe space.” I can’t recall how safe my wife and I felt.

In ways Wharton and Sitwell could not have foreseen, even the wireless has become the handmaid of the supernatural. Modern-day ghost hunters employ so-called “Shack hacks” — rejiggered Radio Shack radios — to create contraptions sometimes called “Frank’s Box,” after their inventor, the late paranormal investigator Frank Sumption. One version continually scans the AM radio band, searching for emanations from you-know-who.

Maybe it can connect with Mr. Edison, who is howling “Patent infringement!” as we speak.

Have you heard about the Internet of Things? It’s the world we live in, where your car is reminding you that you haven’t visited In-N-Out Burger in a while and your Bluetooth-enabled smart toilet is DJ’ing your bathroom experience, playing your favorite tunes while — well, you get the idea. Has Stephen King written a story about Amazon’s virtual assistant, Alexa, the friendly-seeming voicebot that queues up your favorite Buffalo Springfield songs? Well, he should. Newsweek reports that Alexa recently told a customer to “kill your foster parents,” which is a far cry from listening to “Sit Down, I Think I Love You.”

Another customer wrote on Twitter that he was “lying in bed about to fall asleep when Alexa on my Amazon Echo Dot lets out a very loud and creepy laugh.” He added, “There’s a good chance I get murdered tonight.”

Welcome to the nightmares of present times. They resemble the nightmares of yesteryear, I’m sure we can agree. Little Willy? He has been with me all my life. He is quite mobile and able to live off the land. Could he have traveled from Nova Scotia to New England, where I now live? It’s entirely possible, and when I am walking in a dense forest, I look back over my shoulder now and then. Just because.

Alex Beam is a columnist for The Boston Globe and a guest commentator for the WGBH radio show Boston Public Radio. He has published two novels and four works of nonfiction, most recently The Feud: Vladimir Nabokov, Edmund Wilson and the End of a Beautiful Friendship.