In October 2017, a telescope in Hawaii detected the first confirmed “interstellar object” spotted in our solar system. Christened ‘Oumuamua (pronounced oh-MOO-uh-MOO-uh), Hawaiian for “messenger from the past,” it became an astronomical cause célèbre.

A wealth of anomalous data fueled curiosity. Beyond its pancake-like shape, high reflectivity and a strange rotational pattern best described as “tumbling,” the stadium-sized visitor tracked a peculiar trajectory. Instead of being dragged into the sun’s orbit so astronomers could get a better look, it actually accelerated on its way out of the solar system. “The more we found out about this object,” Harvard University astronomer Abraham Loeb told Spiegel Online, “the weirder it got.”

This past November, Loeb and astrophysicist Shmuel Bialy floated a theorem that synthesized the latest data. Perhaps, they proposed, ‘Oumuamua was a “lightsail” whose vast surface area, relative to its mass, was propelled by photons escaping the sun, like a catamaran driven by the wind caught in its canvas.

Crunching a dizzying series of calculations, the pair showed that the only consideration for which they couldn’t account with their lightsail concept was the stuff of which ‘Oumuamua was made. In this case, it would represent “a new class of thin interstellar material,” they wrote in their report to The Astrophysical Journal Letters, a scholarly publication for the rapid dissemination of novel findings. If not produced naturally, through an as-yet-unknown process, maybe ‘Oumuamua was just space junk.

Then things got interesting. “A more exotic scenario,” Loeb and Bialy wrote, “is that ‘Oumuamua may be a fully operational probe sent intentionally to Earth.”

Their scholarly claims of an alien probe rocketed to No. 2 on NBC’s list of top space stories of 2018, eclipsed only by the successful Mars landing by NASA’s InSight. Detractors vilified them for wild speculation. Loeb, chair of Harvard’s Department of Astronomy and author of some 700 peer-reviewed papers in the field, defended their honor. “We should examine each and every interstellar object entering the solar system to check if it’s natural or not,” he told NBC. “Even if most of the time it’s natural, every now and then we might be surprised.”

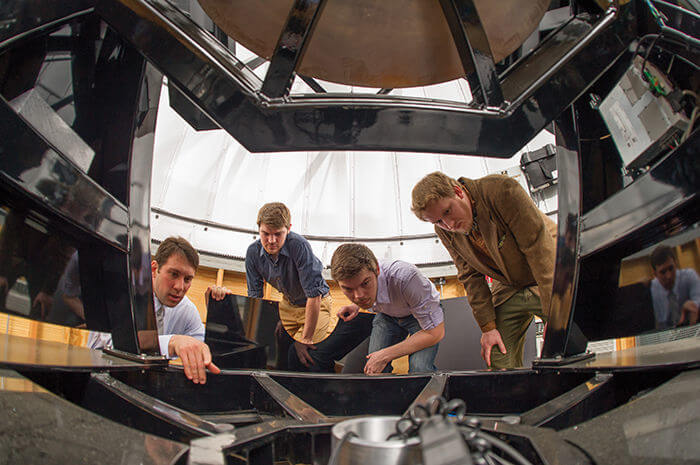

Percival Lowell mapped Mars in the 19th century, while Notre Dame’s Justin Crepp (left) designs telescopes to seek life beyond Earth in the 21st. (Photo by Matt Cashore ’94)

Percival Lowell mapped Mars in the 19th century, while Notre Dame’s Justin Crepp (left) designs telescopes to seek life beyond Earth in the 21st. (Photo by Matt Cashore ’94)

We humans have been seeking surprises from the cosmos for as long as we’ve been gazing heavenward. Much of the curiosity boils down to a single query: Are we alone? “That’s an age-old question that we’re starting to be able to address with scientific rigor for the first time,” says experimental astrophysicist Justin Crepp, who designs and builds instruments for the largest telescopes in the world in a quest to identify planets that might support life.

An associate professor of physics and director of Notre Dame’s Engineering and Design Core Facility, Crepp is hardly a fringe weirdo. In 2013, NASA awarded him an early career fellowship for his work in high-contrast imaging. More recently, the National Science Foundation gave him a career fellowship to build a tool for the Large Binocular Telescope in Arizona. Crepp’s high-tech gadget corrects for atmospheric turbulence to bolster detection and imaging of planets beyond our solar system. When the National Academy of Sciences assembled a committee to set priorities in the search for such heavenly bodies — exoplanets, in astronomical parlance — Crepp was among the scientists they invited to weigh in.

“We don’t know what we’re going to learn,” Crepp admits, and that’s all the more reason to keep exploring. Any discovery of extraterrestrial intelligence, whether those beings send a probe our way or merely bide their time until we come knocking, is sure to have implications far beyond astronomy — in biology, theology, sociology, geopolitics.

Humans won’t break out of our solar system any time soon, he says, but that’s no rationale for a strictly isolationist policy. Laser bursts, for example, might serve as a kind of interstellar Morse code. “We could communicate with these beings,” says Crepp. “If they’re alive and intelligent, they’re almost surely more advanced than we are — so we have a lot to learn.”

Space invaders

Scientists — and society at large — haven’t always been so sanguine about such encounters. “If aliens visit us,” Stephen Hawking once declared, “the outcome would be much as when Columbus landed in America, which didn’t turn out well for the Native Americans.”

Such anxieties about interplanetary colonialism feature prominently in The War of the Worlds, a late 19th-century thought experiment by British author H.G. Wells. The hostile Martians armed with ray guns may have been a figment of Wells’ imagination, but the science was current. By the time the popular novelist started spinning his yarn, his readers knew that two decades of scholarship on the Red Planet’s arid terrain suggested that the locals were fast running out of water — if they hadn’t already.

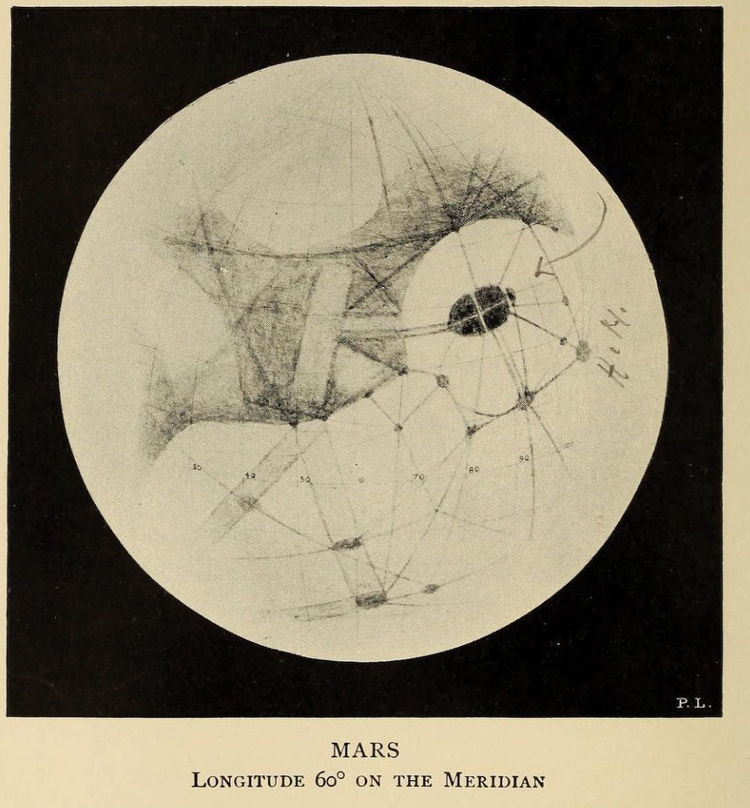

In the late 1870s, an astronomer in Milan had detected a tangle of channels spanning the planet’s surface — canali, in Italian, mistranslated to “canal.” Those reports sparked the curiosity of the American astronomer Percival Lowell, who would go on to establish the Flagstaff, Arizona, observatory that today bears his name. Lowell’s scholarly tome Mars, published in 1895, included maps detailing what Lowell posited were irrigation channels running from the polar ice caps to the planet’s equatorial population centers. The advanced civilization behind the waterworks was in peril, he hypothesized. In essays penned for The Atlantic Monthly and The New York Times, Lowell brought his theories to the masses.

Wells explored the social implications of Lowell’s ideas to dramatic effect through a serial tale of extraterrestrial climate-refugees launching a hostile takeover. As the story traversed the globe, its setting shifted for maximum impact. In England, spaceships disgorged alien crews in Surrey. Randolph Hearst’s New York Evening Journal carried a pirated version in which Martian crews disembarked in New Jersey, blazing a swath of destruction to New York. New England’s daily paper of record had the Martians beating a path from Concord to Boston.

Robert Goddard was a teen when the Boston Post account sparked his imagination. Figuring out how to escape Earth’s atmosphere would become his life’s work. In 1926, the physicist’s first liquid-fueled rocket soared 41 feet in the air and 184 feet from a launch tower on his Aunt Effie’s farm in the Boston exurbs. It smashed on impact. Undeterred, Goddard decamped to Roswell, New Mexico, where the weather was more suitable for year-round experimentation.

“Moony” Goddard tried building a rocket to make a lunar landing in the 1920s.

“Moony” Goddard tried building a rocket to make a lunar landing in the 1920s.

At the time of his death in 1945, interplanetary travel remained more fiction than science, but the derision that had earned Goddard the moniker “Moony” for his youthful ambition to explode a rocket on the lunar surface was fading fast. In 1944, the Nazis had wrought havoc in England and France with their V-2 missile, a rocket that could travel some 200 miles with a one-ton payload of explosives and hit its target at more than 4,000 miles per hour.

Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that prior to World War II, eyewitness accounts of unidentified flying objects were largely dismissed as flights of fancy. Philosophers speculated about extraterrestrial life, but humans weren’t going anywhere. Witness “Moony,” his rockets crashing in the desert throughout the 1930s.

Hello out there

In the postwar era, however, Americans were on top of the world. They’d bounced back from Pearl Harbor, engineered an atomic bomb, captured the German scientists responsible for the V-2 and defeated the Axis. Soldiers were home. Manufacturing and discovery were booming. Space was the next frontier.

Soon a witness so credible he might have been plucked from central casting dragged the question of extraterrestrial intelligence into sharp relief. At 6 feet and 220 pounds, Kenneth Arnold cut a commanding figure. A nationally competitive diver in his youth, he had launched a profitable business selling fire-suppression equipment throughout the Pacific Northwest. With a wife and two daughters in Boise, Idaho, he’d earned his pilot’s license and bought a Call-Air A-2 to reduce his commuting times. By the summer of 1947, the 32-year-old had logged some 9,000 flying hours, half of that time as a volunteer on search and rescue missions.

That’s how Arnold learned of a U.S. Marine Corps transport plane downed in the Cascades — and the $5,000 reward for whomever found the wreckage. On June 24, 1947, he took a fateful detour en route to an air show in Pendleton, Oregon, to scan the southwest slope of Washington’s Mount Rainier, where the plane had last been spotted. When a bright flash lit up his A-2, the pilot scanned the skies, fearing he’d narrowly missed colliding with another aircraft.

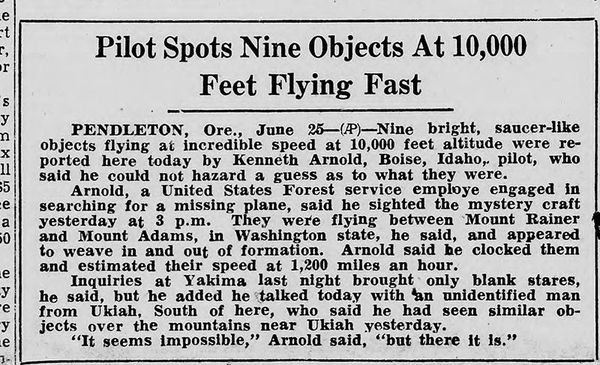

Suddenly a fleet of nine metallic objects caught Arnold’s eye. Flying in formation, they cut a stark contrast against Rainier’s snowcap. For two minutes, he watched the vessels — moving at more than three times the rate of any conventional aircraft and “flying like a saucer would” if skipped across water — until they disappeared in the southern sky.

In Pendleton, reporters for the East Oregonian pumped Arnold for details on what he assumed had been a military exercise. His primary concern was whether the operation was American or Soviet. The next day a 191-word snippet appeared in the paper’s evening edition under the headline, “Impossible! Maybe, but Seein’ is Believin’, says Flyer.” The next day, a follow-up included quotes from military officials unable to account for what Arnold had seen.

The story flew around the world on the Associated Press wire service, while newspapers throughout the United States were flooded with reports from locals who’d witnessed similar things. On July 5, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer published the first photos of an alleged flying disc, provided by a U.S. Coast Guard administrator.

Three days later, the U.S. Army weighed in, with a statement detailing the recovery of debris near Roswell. “The many rumors regarding the flying disc became a reality yesterday when the intelligence office of the 509th Bomb Group of the Eighth Air Force, Roswell Army Air Field, was fortunate enough to gain possession of a disc through the cooperation of one of the local ranchers and the sheriff's office of Chaves County,” declared the press release.

The 509th was widely known as the unit whose pilots had completed the high-stakes mission to deliver the atomic bombs credited with ending World War II. Their national standing only added to the Roswell story’s reach. The War Department issued a retraction the next day — the debris was merely scrap from a busted-up weather balloon, officers explained — but they were too late. Flying saucers had taken the world by storm.

Later that summer, the federal government established the U.S. Air Force as an independent branch of the military. Among its charges: Document and investigate UFO sightings to assess their threat to national security; collect and analyze the corresponding data. Conducted under the code names Project Sign, Project Grudge and Project Blue Book, the effort — subject of a History Channel miniseries that aired this past January — compiled more than 12,000 reports over 20 years, managing neither to verify nor disprove the visitations.

Critics were incensed. The government was engaged in a cover-up of galactic proportions, they claimed. And, no less galling, the Air Force had evinced incompetence in the handling of scientific data. Finally in 1966, hoping to jettison the UFO question once and for all — without fueling conspiracy theories about where they had been hiding two decades’ worth of alien corpses and flying saucer debris — the Air Force commissioned an independent team of scientists led by University of Colorado physicist Edward Condon to review its files and issue a definitive judgment.

Considering the number of stars in the universe and the likely number of Earth-sized objects orbiting at a suitable distance to support biological activity, Fermi reasoned, there must be other planets where life could have emerged.

“I went in thinking there’s a fairly good chance we’ll find something extraordinary,” says planetary scientist William Hartmann, who was a member of the Condon Committee. “I wasn’t taking the point of view of debunking the claims, but stretching the possibilities, thinking maybe we’ll find something interesting.”

If there was something interesting, Condon and his team couldn’t find it in their two-year review. Some of the hoaxes were obvious: shadows inconsistent with the date, time and location from which a photo had supposedly been taken; Polaroid images captured out of order; post-hoc confessions from perpetrators. Other reports were cases of mistaken identity — swamp gas, missile tests or radar anomalies; Venus, the Moon or the aurora borealis, to name just a few.

Satellites, too, played their part. On March 3, 1968, for example, hundreds of witnesses from Massachusetts to Kentucky reported seeing brightly lit objects speeding across the night sky, leaving a trail of sparks in their wake. Moscow later confirmed the corresponding launch — and spectacular failure — of the lunar probe Zond 4.

“It’s not that we concluded that every single report was a falsehood,” says Hartmann of the committee’s final recommendation that the Air Force abandon Project Blue Book. “It was just a question of whether there were credible cases that we thought we could defend.” Unlike a rigorously designed experiment that yields verifiable data, the Air Force files were riddled with fraudulent, mistaken and incomplete accounts. “Even if we knew that one of those flying saucer cases were an honest-to-god alien spaceship,” he says, “I don’t think we could pick out from all of the UFO reports which was the one. There’s just too much noise there.”

Despite the eminence of Condon’s team, whose report was published in 1969 by Bantam Books, public speculation about UFOs persisted. In December of that year, the American Association for the Advancement of Science hosted a two-day symposium on the topic organized by astronomers Carl Sagan, Thornton Page and others. By hosting a debate among scientists with conflicting perspectives, they hoped to demonstrate how the scientific method could be brought to bear on a subject of great public concern while promoting scientific literacy.

In addition to a few Condon Committee members, the invited speakers included tenured psychiatrists and sociologists, experts in radar, atmospheric science and physics, and even the science editor for The New York Times. “Scientists, being human beings, do not always approach controversial subjects dispassionately,” Sagan and Page wrote in their compilation of the proceedings, “and the reader will occasionally find in these pages the heat of passion as well as the light of scientific inquiry.”

Much of the debate boiled down to whether the scientific method could be applied to the UFO question, given the conspicuous absence of reliable data. The astronomer J. Allen Hynek — a scientific advisor to projects Sign, Grudge and Blue Book — believed it could. In 1973, in hopes of uncovering the kind of data scientists would embrace, he founded the Center for UFO Studies (CUFOS), a citizen-run enterprise which to this day investigates potential sightings.

Hartmann came to the opposite conclusion and devoted his career to matters of interplanetary imaging and the evolution of planetary surface features. Now an emeritus scientist with the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, he served on the imaging teams for three Mars missions — including as co-investigator of the Mariner 9 mission, which for the first time mapped the Red Planet’s surface from orbit. Such work disproved once and for all Lowell’s hypotheses about parched Martians and the demise of their civilization.

Meanwhile, a cadre of investigators, Sagan among them, would explore a question they found more interesting than UFO verification and more compatible with the scientific method: the Fermi paradox.

Back in 1950, during a lunch break among physicists at Los Alamos National Laboratory, talk turned to the latest UFO reports. Among the snacking scientists was Enrico Fermi, the Italian physicist who had built the world’s first nuclear reactor on what had once been a University of Chicago squash court.

Considering the number of stars in the universe and the likely number of Earth-sized planets orbiting at a suitable distance to support biological activity, Fermi reasoned, there must be other planets where life could have emerged. Given as well the exponential speed of technological development in our own relatively young planetary system, the great physicist continued, it seemed certain that some of those beings must have achieved interstellar communication and travel.

So, if all those things are true, he asked, “Where is everybody?”

At the time, the most promising way of answering Fermi’s question was by monitoring the microwave and radio frequencies coming from outer space, an endeavor known as SETI, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. Funded intermittently by NASA from the late 1960s until Congress cancelled the program in 1982, the effort was popularized in Sagan’s 1985 novel, Contact. Jodie Foster starred in the 1997 silver-screen adaptation.

As the American space program matured, Sagan campaigned to issue greetings to our interstellar siblings with every mission, just in case they stumbled upon the artifacts of our cosmic exploration. When the Voyager probes launched in 1977, each contained a Golden Record, an internationally representative compilation of analog images and sounds. In addition to nature sounds and 90 minutes of music gathered from Australia to Zaire, spanning Bach to Chuck Berry, were salutations in 55 languages.

Linda Salzman, married to Sagan at the time, provided artwork for a plaque describing the craft’s Earthly origins, and the couple invited their 6-year-old son, Nick, to record the English language greeting. “Hello from the children of planet Earth,” he intoned.

Now a 48-year-old creative whose credits include a trilogy of futuristic novels as well as computer games and screenplays (most notably episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Voyager), Nick Sagan admits it’s strange and cool that his voice will continue hurtling through space long after he’s dead. Almost assuredly, he says, we’re not alone — the universe is too vast. And while he shares his father’s skepticism about UFOs, his own speculation about why we haven’t been visited is decidedly sci-fi: “They don’t want to interfere with us, out of some concern about our development — it’s the Star Trek prime directive.”

The watchers

Michael Swords ’62 was 18 when he and his brother saw a domed-disk UFO from their home in St. Albans, West Virginia. After completing his doctorate at Case Western Reserve University in the history of science and technology, he landed a post at Western Michigan University teaching natural sciences in 1971. Soon after, he joined CUFOS, Hynek’s citizen-science enterprise to bring rigor to UFO investigations.

For decades, Swords taught Science and Parascience, an introduction to scientific methodology. Students picked a topic — UFOs, parapsychology, near-death experiences and the like — then evaluated evidence and alternative explanations. “Students loved this as much as the WMU faculty hated it,” says Swords, now a professor emeritus and longtime member of the CUFOS board. During his three decades at Western Michigan, he published some 100 articles on extraterrestrial intelligence, the Air Force inquiries and the characteristics of UFOs as reported. He served five years as editor of the peer-reviewed Journal of UFO Studies, authored Grassroots UFOs, and co-authored UFOs and Government: A Historical Inquiry.

General sightings remain high, he says. In late 2004, the USS Nimitz and USS Princeton detected a white, Tic Tac-shaped object about 100 miles from San Diego. Fighter pilots dispatched from the Nimitz captured infrared video — released by the Pentagon in 2017 — and reported anomalous disturbances on the ocean surface. In 2008, radar archives confirmed dozens of eyewitness reports of a UFO not far from Fort Worth, Texas. In 2010, during the El Bosque air show near Santiago, Chile, three videographers captured footage of unidentified aerial phenomena. In 2017, The New York Times reported on the Pentagon’s Advanced Aerospace Threat Identification Program, a five-year, $22-million effort that investigated myriad accounts, including the Tic Tac case.

And yet seeing isn’t always believing, as developments in Roswell made clear. Nearly five decades after the Army’s 1947 press release claiming it had solid evidence of a flying disk, the Air Force confirmed Project Mogul, a classified attempt during the early Cold War to use high-altitude balloons twice the height of the Statue of Liberty to detect evidence of Soviet atom-bomb tests. In 1995, a 17-minute black-and-white film that Fox News screened three times claimed to document the 1947 necropsy of an alien corpse recovered from the Roswell wreckage. Skeptics objected, but it wasn’t until 2006, when a creative team confirmed they’d made the film, that the hoax was finally debunked.

That hasn’t stopped the people of Roswell — home to the International UFO Museum and Research Center, as well as the annual UFO Festival — from cashing in on the notion of little green visitors.

Sorting hoaxes from credible accounts is no different a task than it ever was, says Swords, and the conflation of entertainment with scientific exploration further muddies the waters. “The [media] image of the UFO researcher is that of a wacko, a con man, a liar,” says Swords. “None of the people that I call my colleagues fit any of that.”

In 2006, Carl Sagan’s widow, Ann Druyan, compiled his transcripts from the 1985 Gifford Lectures, a series devoted to natural theology. In The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God, he reflects on the topic of extraterrestrial life. “I am hardly opposed to the idea of extraterrestrials visiting us,” he declared, noting that he could not exclude the possibility that Earth had already hosted interplanetary explorers. “But precisely because the stakes in the answer are high, precisely because this is an issue that engages powerful emotions, we would in this case demand only the most scrupulous standards of evidence.”

Sharon Tregaskis reported this magazine’s spring 2018 feature on gene editing. Her first visit to a movie theater featured E.T. More recently, she's been digging into the otherworldly tales of Octavia Butler, Nalo Hopkinson and N.K. Jemisin.