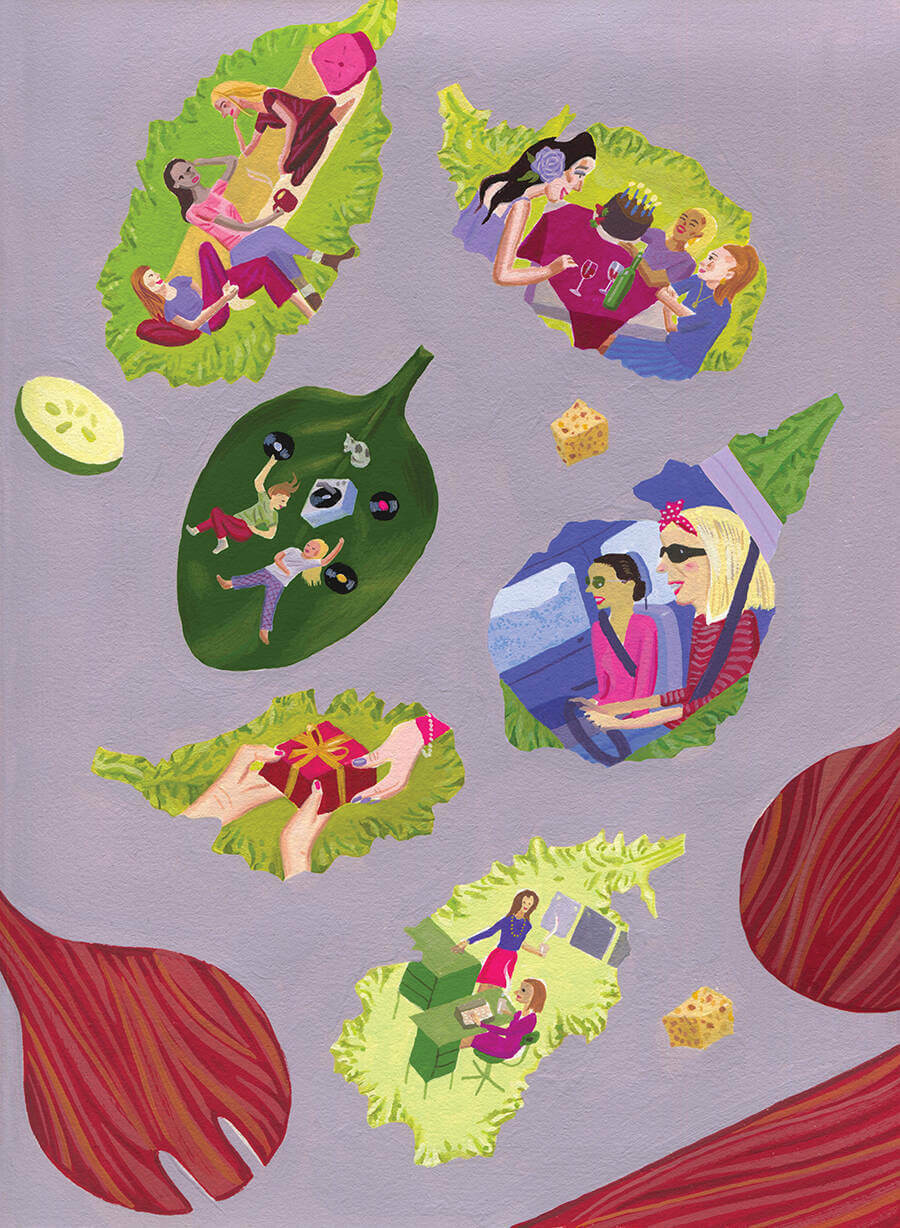

Illustrations by Juliette Borda

Illustrations by Juliette Borda

- Sisterhood

- Sistering, Sheila Weller

- My Warm Spot, Genevieve Redsten ’22

- Who Do I Say I Am? Maraya Steadman ’89, ’90MBA

- The Ones Who Came Before, Elizabeth Hogan ’99

- A Benevolence of Friends, Mary McGreevy ’89

- Still Some Loose Threads, Maggie Green Cambria ’88

- Flame Launcher, Interview by Tess Gunty ’15

- Rider on the Storm, John Rosengren

- Under the Long Haul, Abby Jorgensen ’16, ’18M.A.

- Writing Her Own Script, Madeline Buckley ’11

- Callings Unanswered, Anna Keating ’06

- Much More than Baby Talk, Adriana Pratt ’12

- Undeterred, Abigail Pesta ’91

- The Good Place, John Nagy ’00M.A.

- Scene Setter, Jason Kelly ’95

- She’s Got Game, Lesley Visser

A few years after I moved to New York after college — a ridiculously too-many years ago — I made friends with the two women who would become, among a number of amazing female friends I have, my two what-they-call-now “besties.” I first met Eileen — a tall, strikingly black-haired woman from New Jersey — and, later, Carol: petite like me, fast-talking, from Ohio. I was from West Los Angeles.

I’d had best friends before, as we all did, from childhood through college, and each friendship had its distinctive flavor and reason for being. But this three-way friendship between Eileen, Carol and me has survived for over 45 years, ups and downs notwithstanding. When we first met, I don’t think I was aware that what appealed to me most was the sense that they would be nurturing to me. And they have been. For this I am extraordinarily grateful. And I hope I have given a bit of nurturance back.

Though she probably doesn’t remember this, Eileen and I agreed, during an early coffee-break conversation at the office of the “hippie” magazine where we both worked, that we were the kind of girls that kids’ parents liked. We were secret pleasers. We were safe with each other, I felt.

As for Carol, I had heard her described, by a mutual friend, as someone who had been married to a major avant-garde composer, a man who had employed me intermittently as a typist. I expected a cool, possibly snobbish young woman. Instead, when I climbed the five flights of stairs to her apartment, and she opened the door, and I said, “I knew your ex-husband a tiny bit,” she pulled me into the apartment and insisted: “Tell me!” Her humorous vulnerability and utter refusal to be cool won me over. I felt I was safe with her, too.

I introduced Carol to Eileen, and we became three-way best friends. We got into a habit of meeting at a local diner on Sunday mornings, since we all lived in the same neighborhood. Over gallons of coffee and plates of bacon and scrambled eggs, we would detail what had happened the night before, and with whom. As we giggled happily over our exploits or agonized about what might happen next, we did our level best to be sounding boards for one another. And despite our being in our early 20s, we also did our level best to give one another the smartest possible feedback and advice. “Women understand,” Gloria Steinem has said. “We share experiences, make jokes, paint pictures and describe humiliations that mean nothing to men. . . . Women understand.” That remark describes how we felt at the end of each Sunday morning breakfast.

But it wasn’t all about our dating lives. We also spent plenty of cozy Saturday nights cross-legged on the floor of my apartment, eating the elaborate salads I made and watching The Mary Tyler Moore Show, loving the characters of Mary Richards and Rhoda Morgenstern and kidding that we wanted to be a combination of the two of them.

We made a pact to have dinner together on our birthdays and, with few exceptions (and a few imperfect evenings), for all these decades we have done so. At these three-times-a-year occasions, we make a reservation at a fancy restaurant, dress up for one another, give flowers as gifts accompanied by birthday cards in which we scribble heartfelt messages. One of these occasions took place just two or three days after 9/11, when we sat in a nearly empty restaurant and mourned together for New York.

Of course, our friendship reached into all parts of our lives. When Eileen wanted to adopt a child, I drove her to Carol’s weekend house in a Connecticut lake community to meet a woman who had adopted a wonderful daughter from an orphanage in Lithuania that Eileen just had to check out. Eileen and her husband contacted the orphanage and were sent a photo of a little girl, Masha. Eileen called me, urgently wanting to meet so she could show me the photo. Masha looked serious and slightly uncomfortable in her too-tight clothes. “I think that’s a sign of strength,” Eileen said, and I loved her for her optimism and spot-on accuracy. I affirmed this by saying, “This is your daughter!” We laughed and clinked our wine glasses. (Today, Masha is an extraordinary young woman, a jewelry designer and homeowner who has conquered learning differences and a brain tumor.)

I made a present for Masha — a calendar with hearts — so she could mark the happy occasion of her adoption. “That meant a lot to her,” Eileen told me just the other day.

The three of us have continued to be friends over all the years. Being writers, we have read, edited and championed one another’s short stories, books and articles. When Carol was dreaming of writing a novella about the three most important loves of her life, I introduced her to the publisher who ultimately published it, and I have always been heartened when Eileen has asked me for advice, respecting my track record as an author.

Over the last several years, I feel I have gotten more from my friends than I have given. I’ve been in the position of the friend who “owes” — health and personal issues have demanded so much of my bandwidth, and I haven’t been able to give to my friends as much attention as I wished. I am writing this essay to honor and thank them and to look at what friendship between women and girls — my friendships and others’ — has been and can be, even taking notes, when relevant, on ways I might be a better friend to the friends who’ve been so good to me.

Ah, girlhood! When you are young, having a quirky history together — a font of private jokes and a private language, a feeling of us-two against the world — is central to friendship. My childhood best friend, Phyllis, and I shared a sense of humor. We did pranky things — at least they were pranky for 10-year-old girls in an upper-middle-class suburb of Southern California. We climbed to the top of the fence behind Phyllis’ house to spy on the neighbors. (This was Beverly Hills, so it may not be surprising that the neighbors were a sultry Spanish movie star and his glamorous movie-star wife.) We braved going to a new gourmet cafeteria without our purses, and we had to wait at a special table for our parents to come and pay our bill and bail us out. We felt giddily like outlaws.

In high school my best friend was Jamie. We lived around the corner from one another and walked to school together every day. She was a stunningly beautiful girl (massive blue eyes, high cheekbones, rosebud lips) who didn’t care about her looks and had gained weight partly to flout her mother, the top hair stylist at the top Beverly Hills salon — which made Jamie appealingly rebellious. We both had crushes on the handsome jocks, and we drove past their houses to “spy” on them through their open windows, wondering if they were talking to other girls and pretending we could read their lips and see what they were saying. We wrote messages about them in our yearbooks, all in initials and codes so no one else would know who we were talking about. In those long-pre-internet days, we had marathon phone calls: dialing up one another after dinner, then talking until we fell asleep and leaving the phone off the hook while we slept, then reviving in the morning — thrilled at how long we had talked.

Jamie had a boyfriend named Cliff, a senior when she and I were sophomores. Driving cross-country during a semester-break trip, he fell asleep at the wheel and crashed and died. It fell on me to tell Jamie what had happened, and I remember every slow step I walked around the block to her house to deliver that message. The wetness of my shoulder after she collapsed on it was testimony to how bonded we were in her grief. She spent several nights in my bedroom; she slept on my bed and I on the floor beside her; we held hands until she fell asleep, and I was grateful for whatever consolation I could give. I tried to push my teenager melodrama — I was helping my friend through this tragedy! — past the almost unbearable, genuine horror of this painfully young and random death.

My college best friend was a sultry, sensual bohemian intellectual named Jean: out of place in our rah-rah sorority and as different from me — a pretending-to-be-sunny-blond high school cheerleader who really visited Black churches on weekends to hear gospel music — as two girls could be. But we had an inner click, and she, a pouting loner, clung to me with a touching dependence. We shared a secret language — making up soulful terms like “ethnosensuality” as we listened to R&B on a record player in our minuscule bedroom. She seemed blissfully self-absorbed — like a sensual cat — while I was always talking to her, earnestly, about the civil rights movement I followed so avidly.

We had very different boyfriends: a sophisticated philosophy professor for her, a wholesome architecture student for me. After we slept with them for the first times, we madly searched the phone book for a doctor who would prescribe contraception without our parents’ permission — an unforgettable pre-feminism ordeal and rite of passage.

Over time I lost touch with Jean, though I thought of her often, and when the internet entered our lives I Googled her and read the notice I should have thought to search for years earlier. She had become a distinguished philosophy professor, known for her social consciousness (had my avidity about the civil rights movement affected her after all?) and had died of breast cancer at 45. A philosophy department building had been named in her honor.

Why hadn’t I raced to find her earlier? I felt guilty and selfish, though I knew she also could have raced to find me. Perhaps our friendship was meant to be a magical one, encased in a special time. I contacted her widower — the philosophy professor, now remarried — and he and I started an email friendship. I heard about their daughters and their travels from one college to another. I told him that everyone in the sorority was fascinated by Jean’s and my friendship. “We were so different!” I said. “Yes, I could tell you were,” he replied. “Sometimes that’s what it takes.”

Friendship between women today has no higher champions — or more sensitive analysts — than the pioneering writer and blogger Ann Friedman, 40, and the tech guru Aminatou Sow, 37. They started their highly successful podcast, Call Your Girlfriend, in 2014, and together they wrote the book Big Friendship: How We Keep Each Other Close, which was published last year. Friedman is white and from Iowa. Sow is Black, from Guinea.

Worldly, bold and politically active, Sow arrived in the United States to study at the University of Texas alone, without her family. She organized Iraq War protests, volunteered at a health clinic and taught women in prison how to read.

They met in Washington, D.C., in their 20s. Friedman knew immediately she wanted to be friends with the charismatic Sow. “Ann began developing a narrative about Aminatou,” they write, in third person, in their book. “Her new friend was a woman of global experience, able to thrive in any situation and impress any crowd, emotionally resilient and possessed of a firm, unwavering opinion about almost everything.” Energetic doers, they both soon discovered they liked to laugh together and to initiate social activity among their wide swath of mutual friends.

Their book is particularly good on the subject of interracial friendship. At one point, “Aminatou let Ann know that throughout their friendship she has had to modulate her emotions so as to never appear too annoyed or to be honest about something upsetting her.” The social cost of expressing anger as a Black woman had affected their intimate friendship, even though Friedman had come into the friendship thinking of Sow as her much-respected superior in sophistication, and even when the women were so close that they wore matching clothes and sported matching tattoos. “We call it frog-and-toading,” they wrote.

The book traces their friendship over many job and city and romance changes and develops a concept they call shine theory. They seized upon it one day when Friedman started “wailing, gratefully, ‘I never could do it without you!’” after Sow had helped her master the skills of budgeting and hiring she needed for a new job. Sow responded, “I don’t shine if you don’t shine.” They were business partners by way of their podcast by then, so the fact that their fortunes were linked made that motto true and pragmatic. But even between friends who have no mutual business self-interest, Sow’s line is a wonderful course correction for the biggest women-friendship killer of all: jealousy. It’s a reminder that women should be “refusing to give in to comparison and competition and trying instead to forge a bond and a connection,” they write.

(I have just typed out “I don’t shine if you don’t shine” and taped it to my computer screen, in case I ever feel a pang of envy toward either of my two best friends, along with a valuable quote from Simone Weil: “Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity,” a reminder to never look at my phone when I am talking to either of them.)

“We are really deeply embedded in each other’s lives,” Friedman tells me in a phone conversation. So admirably fine-tuned has their sensitivity to one another been that several years ago they noted, with grief, that they had started “to keep certain parts of ourselves secret and separate from the friendship.” So they did something that mates often do but friends almost never do: They went into therapy together. They took it so seriously that Sow even flew from her home in New York to Los Angeles, where Friedman lives, so they could make the first sessions in person. They strongly recommend it. “Friendship takes work,” Friedman says.

“There’s an expectation that friendship is the easy part of life. All support, no strife,” they write. “It gets hard? Well, it wasn’t meant to be. Acknowledging friendship’s potential to be one of the deepest and most powerful relationships of our lives also means acknowledging something far more difficult: that its end can cut so deep that the scars might never fully heal. . . . You’re taking an emotional risk. And it’s an even bigger risk than people take when they fall in romantic love, because there are so few rules to guide you through the difficult times.” Earnestly, they pondered whether their miscommunication had gotten so deep that it was time to break up. Both were racked with anxiety. But “despite feeling like we’d repeatedly failed to fix things between us, we weren’t ready to break up yet,” they write. “We each had our own reasons we felt our friendship was worth fighting for.”

That a friendship is worth fighting for is a loving and inspiring idea. Over the years my best friends and I have felt that way. After flare-ups and miscommunications, we’ve made dates to talk things out — and talk things out we have. I can’t say that every such effort has been successful, and there have been periods of weeks and more when two of us have not talked, causing pain. But somehow we have always snapped back, always felt a compelling need to stay together. “Look at these years!” we have said at our birthday celebrations. “We are each other’s memory.”

Sometimes you hear a women’s friendship story that makes you smile, it has such vibrant, funny characters. This exchange I elicited via a Facebook group would qualify.

Caroline Leavitt and Jo Fisher met at Brandeis University in Boston, where both were students in the 1970s. They were fascinated by one another. “Jo was wearing red rubber boots and a sweater with a big N on it, and she said it stood for Nothingness and Nihilism,” writes Leavitt.

“I was scared to approach her at Brandeis,” recalls Fisher. “She was so pretty, so thin — and always had boyfriends. But when we both worked at the college library and stole cookies from the cookie jar, we were bonded. Cookies are a theme” of the friendship, she writes.

Theirs has largely been an epistolary friendship, Fisher says. They have never lived close to one another since college, but, for them, letters do the trick. Like 19th-century correspondents, they started trading intimacies through letters, then by email. “We have been there for each other for 40 years,” says Leavitt, a novelist and co-founder of the literary platform, A Mighty Blaze, “and I cannot imagine life without her. We live in letters and phone calls and the huge birthday boxes we send to each other each year.” They’re “massive cartons of cool earrings, toys and socks,” adds Fisher, who works in a bookstore in Santa Fe, New Mexico. One time Leavitt sent her half a carton of mint Milanos because she didn’t want to devour the whole box.

“We grow closer,” Leavitt says, “because we live in each other’s lives.”

Well aside from these funny gifts, the friendship has had serious meaning and value. Decades ago, when her then-fiancé died, says Leavitt, who has long been happily married to music writer Jeff Tamarkin, “Jo said, ‘Come here,’ and I flew to Santa Fe. Jo took care of me, and when I left a week later, we both cried. Jo can call me day or night and I am there, and we’ve helped each other through breakups.”

Another time, when Leavitt had a manipulative boyfriend who monitored her meals and read her emails, Fisher blew up at her, “and that stunner made me break up with him,” she writes. Fisher tells this story: “When my boyfriend of 19 years left me for some chippy last year, Caroline wrote him a brilliant, cutting letter, which helped alleviate my pain. She will listen to and read my meanderings and love me even more, as well as giving me affirmations and advice.”

The widely regarded platonic ideal of a best-friendship between women may well be that of Oprah Winfrey and Gayle King. As Winfrey said of King: “She is the mother I never had. She is the sister everybody would want. She is the friend that everybody deserves. I don’t know a better person.” But while I print those words on a card and tape them to my mirror, I can’t help but think there are two other sentences — in the ideal of a best-friendship world — that move and inspire me just as much, and those come from Fisher and Leavitt.

“You saved my life,” Fisher says of Leavitt.

“No,” Leavitt replies. “You saved mine.”

I’ll take that.

Sheila Weller is a New York Times-bestselling author and award-winning magazine journalist.