“The anger in me is what is my driving force.”

This is how Sunitha Krishnan has described the root of her life’s work, helping survivors of sex trafficking and their children change their fate.

In my many years of journalism covering women who strive to change the world, I’ve been interested in what motivates them to make a difference. Whether it’s anger, pain or something else, I’ve found a common thread: When these women experience or witness a great sadness or injustice in the world, they don’t retreat from it, but rather run toward it — using their experience to help others, turning adversity into power.

Here are the phenomenal stories of Krishnan and four other world-changing women I’ve had the honor of talking with, and learning from, over the years.

The protector: Sunitha Krishnan

When she was a 15-year-old girl in Bengaluru, India, in 1987, Sunitha Krishnan experienced unthinkable violence — a gang rape at the hands of eight men. Even worse: the stigma she faced afterward. “People blamed me,” she told me during a recent video call from India. “People sidelined me, ostracized me, isolated me for a crime I did not do.”

It was a stunning “fall from grace,” she said. A high achiever, she had sailed through her childhood, excelling in school and spending her spare time teaching special-needs and underprivileged kids. “I would pick my students; I would not teach everybody,” she said. “I would pick only those who were economically weaker, only those who had a very difficult time.” By age 12, she had started a small school for children in slums. She laughed as she recalled her precocious confidence: “I became very righteous. It was very irritating for most people around me. I spoke older than my age; I was the perpetual grandmother.” But she was also roundly admired. “Every parent wanted a daughter like me, every teacher wanted a student like me.”

Her community had high expectations for her, until the assault. After that “crash,” she said, she saw people’s perceptions of her change. “I became the most dishonored person, the most unworthy person. I was made to feel as if I failed,” she said. “I saw both sides by the time I was 16. I saw what it means to be on top of the world, and I also saw what it means to be at the absolute bottom.”

The experience made her angry — and ready to fight.

“I took the next step and said, ‘Why cannot I change this perception?’ For me, it was very clear that even if I’m not going to change it, I’m going to work toward changing it. I’m not going to go to my grave thinking that I never tried.”

But first she needed a strategy. “Anger doesn’t change anything,” she said. “What took time for me was to gain the knowledge, evolve an understanding, and look in a very strategic way at who do I want to reach, and how do I want to reach them? How can it be something that’s not about me, it’s about the world around me?”

I first heard Krishnan speak about the power in her anger at the Women in the World Summit in New York four years ago, and I was struck by her calm demeanor as she described the violence and stigma she had endured. She said her anger had only grown over the years as she saw so many other women being raped and blamed for it. But she channeled that anger into a force for good.

After graduating from college and earning her master’s degree in psychiatric social work, she found a kindred spirit in Brother Jose Vetticatil. A Montfort Brother of St. Gabriel, Vetticatil had been running a technical training institute for boys. When he and Krishnan learned about the clearing of brothels in the Indian city of Hyderabad, they asked some of the displaced women how they could help. The women said they wanted to educate their children and protect them from traffickers. Krishnan and Vetticatil started a school in one of the abandoned brothels in 1996. They called their initiative Prajwala, which means “eternal flame.”

“When Brother Jose joined me, we belonged to two faiths, he coming from the Christian faith and I a very hardcore practicing Hindu, so it was an interfaith response to the problem,” she said. “We also had a very interesting union of our minds; I came from an activist understanding, and he came from an institutional understanding. That was a good blend.”

The pair expanded Prajwala into a major nonprofit organization, rescuing, rehabilitating and providing job training for trafficked women while educating their children. When Vetticatil died in 2005, Krishnan continued her work, opening more schools and shelters in India.

In the past quarter century, working with law enforcement, Prajwala has rescued some 25,000 women and girls, she said. Krishnan has been honored many times for her tireless crusade against trafficking, including by the U.S. State Department and by the Aurora Humanitarian Initiative, a foundation that promotes global humanitarian projects. She has also been physically assaulted by people she angered — traffickers whose work she disrupted. But she keeps going. “When I go to my grave, I go with fulfillment that I did not compromise in my efforts,” she said. “How much of that actually changed the world or changed the perceptions around me, I don’t know. But it will not be because I did not try.”

The advocate: Sandy Phillips

In the moments before her daughter, Jessi, was gunned down at a Colorado movie theater, Sandy Phillips exchanged text messages with her from Texas, happily discussing a planned visit. Jessi told her, “I can’t wait for you to come next week. I need my Mama.” Phillips replied, “I need my baby girl.”

Jessi, a red-haired, hockey-loving senior in college, was busy finishing her degree and looking forward to a career in sports journalism when her life was cut short by six bullets that slammed into her right leg, her abdomen, her left eye. Phillips learned the awful news within minutes of the shooting, when a friend of her daughter called from inside the theater. Phillips could hear screaming in the background. Then she screamed herself and fell to the floor, although she doesn’t remember this — the immediate moments following the phone call are lost to her. Her husband, Lonnie, remembers being jolted awake from sleep that night by her cries.

It has been 10 years since the massacre that left 12 dead and 70 injured at the midnight premiere of The Dark Knight Rises in Aurora, Colorado, in July 2012. Amid her profound grief the next day, Phillips awoke from a fog of sedatives and told her husband, “We need to get involved.” He knew what she meant. A month before Jessi was shot in the theater, she had narrowly missed being caught in another mass shooting, at a mall in Toronto. A few minutes after Jessi and her boyfriend had left the food court, a gunman opened fire there, killing two people and injuring several others. Afterward, a shaken Jessi wrote on her blog, “Every second of every day is a gift.”

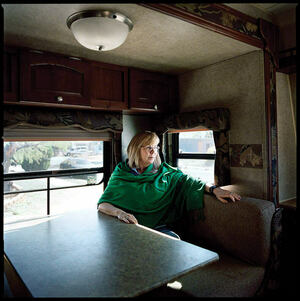

Sandy and Lonnie Phillips not only got involved in the movement for gun safety, they devoted their lives to it. They sold nearly all their belongings, left their home in San Antonio and moved into a camper. Their plan: to travel the country and offer comfort and support to others facing the sudden loss of loved ones to gun violence. They began crisscrossing the United States, helping people navigate the shock and grief from mass shootings. They encouraged other survivors of gun violence to help each other as well, creating a support network that grew into a nonprofit group, Survivors Empowered. They became leading advocates for stronger laws in America, including background checks on all gun sales and limits on the type of gun and the amount of ammunition that can be sold to an individual. A gun dealer had sold some 4,000 rounds of ammunition to the man who killed Jessi, with no background check required.

I have talked with Phillips many times over the years, and I caught up with her recently while she was in San Antonio, a stop on a 22-city tour she launched this year to help members of grassroots gun-safety groups connect and share wisdom across state lines. “We’ve been meeting these people for years,” she told me. “We want to connect small groups with other small groups in other states, so they’re not reinventing the wheel every time they want to get something done.” She noted that this year marks the 10-year “tragiversary,” as she calls it, of the Colorado theater shooting as well as the shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut and a Sikh temple in Wisconsin, among others.

Phillips doesn’t spend her time “living in the past,” she said, choosing instead to live in the moment and honor Jessi by striving to make a difference. Of course, as a survivor of trauma, she feels triggered every time she sees another mass shooting in the news or visits another family suffering from loss. She and Lonnie manage to calm themselves by practicing mindfulness, meditation and deep breathing. “Sometimes we just need to hold each other, sit quietly with one another and just be,” she said.

The past decade has been a wild ride. Among the highlights, she and Lonnie have met presidents Obama and Biden, appeared on 60 Minutes and befriended musician Jackson Browne, who will donate a chunk of proceeds from a concert in Colorado this fall to their cause. On the other side of the spectrum, they have been harassed by conspiracy theorists, including Infowars host Alex Jones — so-called truthers who spin theories that mass shootings are staged by the government, and that Jessi is alive and well, living it up on an exotic island.

In 2014, the couple sued the gun dealer who sold the ammunition to their daughter’s killer. “We didn’t sue for money; we wanted the dealer to change its business practices,” Phillips said. A judge dismissed the suit — federal law protects gun dealers from liability when crimes are committed with their products. Phillips and her husband were ordered to pay more than $200,000 in legal fees to the dealer, and the couple filed for bankruptcy. The dealer later sold ammunition to a minor who killed 10 people at a high school in Texas in 2018, and families of the victims are suing; federal law also prohibits dealers from selling ammunition to minors.

Along the way, the couple have made many friends. Strangers have welcomed them into their homes; church groups have raised funds to support their work. “People often say, ‘You’re welcome to stay with us when you come through town,’” she told me. “We don’t have a lot when it comes to money, but we have a lot in terms of blessings.”

Sometimes Phillips needs to step away from advocacy and social media for a day or two, but she always returns to her mission. “We’re not saying guns are bad,” she said. “We’re saying people are dying; laws can be improved to save lives. We just don’t want to see the suffering that we’ve seen time after time.”

The visionary: Zainab Salbi

When Zainab Salbi was a girl growing up in Baghdad, her father became the personal pilot for Saddam Hussein — not a job he wanted, but he dared not defy the ruthless dictator. Saddam’s presence invaded her household like a “poisonous gas that leaked into our home,” she has said. The family lived in fear, feigning loyalty to a man who used torture, rape and murder to maintain power. As Salbi grew into a young woman, her parents faced a new fear: Saddam’s overt interest in their daughter.

So in 1990, when she was 20 years old, Salbi was spirited away to an arranged marriage in America. But she found no peace in the abusive marriage. She fled and became driven to help women lead independent lives, launching the nonprofit Women for Women International in 1993 to help women in conflict zones learn skills to escape poverty and support themselves and their families.

Over the decades, the organization has helped more than 500,000 women carve out new futures, while Salbi expanded her work, traveling the world to shed light on social issues. She produced a range of documentaries and news shows on PBS, HuffPost and Yahoo! News. In one powerful segment, she met with French families whose sons had joined the Islamic State group, giving insight into how the young men became radicalized. She also hosted a talk show on TLC for women in the Arab world, kicking it off by interviewing Oprah Winfrey. National magazines from Foreign Policy to People celebrated her as a world changer. Our paths crossed many times, and I was always struck by how her eyes sparkle with ideas. She was always on the go.

Then, in the summer of 2019, Salbi’s life took a turn that made her slow down and think about the world in a new light.

It started on what she would’ve once considered “a perfect New York City day,” she said. Fresh off a speech at the Ford Foundation the night before, she had planned to give another presentation that day, followed by a birthday party and a trip to Athens with friends. Her life was a whirl of the “busyness and success that we all value” when crushing pain sent her to the doctor. Soon she was rushed into surgery to drain a quarter gallon of liquid that was pressing on her heart and threatening her life.

“In that moment of thinking, this is it, I am taking my last breath, the first word that came to me was ‘kindness,’” she said. “The second thought was, did I live my life in kindness to myself and to others?” At the time, she wasn’t sure exactly what that meant. “Until that moment, I never thought about myself; I honestly did not know what it means to live in kindness to oneself.” She had always thought self-care meant “getting massages, getting manicures, pedicures, going on vacations — things that we all measure as joy, as success.”

It was time to look deeper. In “that intimate moment between life and death,” Salbi said, she was surprised to realize that accomplishments didn’t matter, despite having spent her life as a humanitarian. “I don’t think just because I’m a cause-oriented person my measurements are superior to others’,” she noted. “The attachment to that notion of success is where the issue is.”

Eventually diagnosed with severe Lyme disease, the experience set her on a new path. “I was really disabled from all my capacities; I couldn’t walk, I couldn’t breathe, and my abilities to think and articulate words also became very hard,” she said. Disconnected from “all these tools,” she found that “the only thing you can do is to really go into yourself.” She moved to a cabin in upstate New York, and, with the help of an innovative doctor, started taking small steps toward recovery such as eating healthful foods and walking forest trails. She found joy in nature and in taking time every day to talk with family, play the piano and create a quiet, reflective moment that she calls an “appointment with my heart.”

In the 18 months it took to regain her strength, she found inner peace. “I came out of this experience finding joy, and the joy did not come from travels or busyness or career success. I just found joy from within,” she said. “I thought, if I can connect in such a profound way to my heart, to Earth, to God, to others, I want to do everything and anything possible to contribute to showing people that they, too, can feel that joy and that happiness.”

To that end, she has co-founded two new initiatives. One, FindCenter, is a platform for personal and spiritual growth where people can share literature, artwork and ideas to help each other navigate life’s challenges. They can also attend free classes and listen to Salbi’s podcast, Redefined, in which she interviews people from all walks of life about how they transformed their lives. “It’s a platform for those who are interested in connecting to themselves, to their hearts and to the divine,” she said. “People can curate their own journey.”

The other initiative, Daughters for Earth, supports women-led conservation and restoration projects that combat climate change. “It’s my contribution to Mother Earth,” she said. “We’ve got to mobilize and put more money in the hands of women who are actively and engagingly doing everything possible to protect and preserve Earth, but no one is paying attention to them.” In her most vulnerable time, when she was struggling to walk, she said, the forest was there for her. “I honestly felt that the Earth was my cheerleader. I would go on the trails, slow-walking, and I felt each tree was telling me, ‘You can do it.’” She wants to return the favor.

- Sisterhood

- Sistering, Sheila Weller

- My Warm Spot, Genevieve Redsten ’22

- Who Do I Say I Am? Maraya Steadman ’89, ’90MBA

- The Ones Who Came Before, Elizabeth Hogan ’99

- A Benevolence of Friends, Mary McGreevy ’89

- Still Some Loose Threads, Maggie Green Cambria ’88

- Flame Launcher, Interview by Tess Gunty ’15

- Rider on the Storm, John Rosengren

- Under the Long Haul, Abby Jorgensen ’16, ’18M.A.

- Writing Her Own Script, Madeline Buckley ’11

- Callings Unanswered, Anna Keating ’06

- Much More than Baby Talk, Adriana Pratt ’12

- Undeterred, Abigail Pesta ’91

- The Good Place, John Nagy ’00M.A.

- Scene Setter, Jason Kelly ’95

- She’s Got Game, Lesley Visser

The witness: Lynsey Addario

Lynsey Addario captured a defining moment of the war in Ukraine when she took a photograph of a mother and her two children who were lying dead on the road after a mortar shell struck a civilian evacuation route. The photo, which ran on the front page of The New York Times in the early weeks of the fighting, revealed the reality of life for civilians, countering Russia’s claim that it was aiming only at military targets. Addario showed the world the truth.

For more than two decades, Addario has traveled to some of the darkest corners of the planet for her Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalism. She has been held captive twice, once for eight hours by gunmen in Iraq and once for six days by soldiers in Libya, during which time she was punched in the face, groped and threatened with death. After her ordeal in Libya, in 2011, she told me, “I was thinking, ‘I need to get out of here alive.’ I was also thinking maybe it’s time to get pregnant.”

She achieved both goals, and today has two children. Back home in London with her kids and husband in April, just a few days after leaving Ukraine, she spoke with me about the circumstances of the haunting photo. To document the war’s civilian toll, she had set her sights on Irpin, a small city outside Kyiv, where she had seen images of people walking across a destroyed bridge to evacuate. “I saw these civilians crossing, people carrying their loved ones,” she said. “I thought, OK, tomorrow we’re going to go there.” It seemed safe, she said, because many journalists were there, and the bridge was on a widely known evacuation route — which she thought would be respected as part of the “laws and norms of war.”

She arrived at the bridge early the next morning. “It was pretty tense from the beginning,” she said. “There was small-arms fire right away, artillery close by.” Russian fire came ever closer to the bridge. “Finally a round landed maybe 30 feet from where I was standing,” she said. “It was chaos. I couldn’t really tell if I had been injured myself — my neck got sprayed with gravel; I thought maybe it was shrapnel. Everything was really dusty. I couldn’t really see what was going on, so I immediately just started shooting what was in front of me.” When her security adviser cleared her to move forward, Addario saw the bodies of the family.

“The first thing I noticed was these little moon boots and puffy coats and the fact that there was a knapsack still on the back of this child,” she said. “Everyone was kind of laying in this position as if they had been knocked over by the wind. I was trying to make sense of this scene. It sounds crazy, because I had been photographing civilians fleeing — that’s why I was there — but for some reason I just didn’t think they would be targeted. I wasn’t really prepared to see a family. I instinctively just started shooting because I felt like I know what I just witnessed and I need to take photographs, but I also was trying to keep my emotions in check because I was pretty shocked at what I was seeing.”

Then the mortar fire resumed, and Addario ran for her car. She filed the photos that day, telling her editor she hoped the paper could publish the image showing the family’s faces. “I felt it was very important.”

After the photo was published, Addario found the father from the slain family and met with him. “That was so hard; I’m the person who captured that horrific moment that will live with him forever,” she said. “He said that he would have made the decision to publish the image had we been able to reach out to him, but I think also it must have been really difficult for him; I just can’t imagine how difficult it is to see your family laid out there. To me he was so brave, and he was so strong; I was the one who was sort of crumbling in tears, and he was stoic.”

It was “fundamentally important to me,” she said, that he felt the image wasn’t gratuitous but served a purpose and “rallied people around the world to talk about the civilian toll of this war. It certainly meant a lot to me as a mother and as a wife and as a person.”

The daughter of two hairstylists in Connecticut, Addario grew up taking photos as a hobby, then moved to Argentina after college to learn Spanish. There, she became interested in photojournalism. “I went into the local newspaper and was like, ‘Give me a job,’” she said with a laugh. She loved that she could use her camera “as an excuse to get to know people, to travel, to move around, move in and out of these very intimate spaces.” Later she began freelancing, bringing her camera to Afghanistan despite a ban on photography because she had read about women being denied their rights under Taliban rule.

When I asked if her approach had changed over the years, she said, “I think I’ve grown up. I have a family now; I understand what it’s like to be a parent. I also feel like I’m a little more delicate in my approach. I’m always kind of asking permission, not if I’m in combat, but if I’m in a situation where I can introduce myself and talk about why I’m asking all these questions of someone.

“When I was younger, I just assumed that I had a right to be there because it was a war and the world needed to see, but I think people all have the right to say, ‘I need my privacy, and this is a really traumatic moment.’”

Her family keeps her grounded when she returns from war. “I don’t really have the luxury of just kind of wallowing in what I’ve seen. I have to just turn around and be a mom,” she said. She exercises “fanatically” to stay mentally and physically strong. “The question that I get asked all the time is: Why do I keep going back? How can I do this job? And it’s so simple for me. You see the importance of these photographs, you see the importance of having the truth be documented by me and all of my colleagues. And so, how can I not do this?”

The peacemaker: Leymah Gbowee

Leymah Gbowee was 17 when war broke out in her native Liberia in 1989, transforming her from a college student with dreams of becoming a doctor into an adult responsible for finding food for her family. “Every day, I went out to look for food. I saw bodies, people being shot. My mother had sunk into a state of total traumatization,” she has said. “You’re just existing, you’re alive. There’s nothing to look forward to.”

Gbowee spent more than a decade trying to survive and “waiting for a white knight” before she realized it was up to her to change her life. She began mobilizing women, creating a coalition of Christians and Muslims to demand peace as the country’s civil war persisted. She organized demonstrations where the women dressed in white — as well as a “sex strike” in which women withheld sex from their husbands. The movement, which started with a handful of women, grew to thousands across the small West African country. At one protest, women locked arms outside a conference hall full of male leaders in the capital of Monrovia, barring them from leaving until they made progress toward peace. Security guards threatened to arrest Gbowee, and she issued her own threat in return: to strip naked on the spot. The guards backed down.

Men were “shocked at the tenacity of the women,” she has said, noting that many of the women had been raped and victimized during the war but had gathered the strength to stand up to men and insist on peace. “The men were looking at us and saying, ‘Is this for real?’ They couldn’t believe it. This is a lesson for any women looking for something from men: As long as we continue in a position of weakness, they will never respect us.”

In 2003, the women achieved their goal, ousting the country’s warlord president, Charles Taylor, and paving the way for Africa’s first elected female head of state, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. Gbowee then earned a master’s degree in conflict transformation at Eastern Mennonite University in Virginia and continued her work with women in Africa to build sustainable peace. In 2011, she received the Nobel Peace Prize for her work, sharing the honor with Sirleaf and the Yemeni activist Tawakkol Karman.

But Liberia had a long way to go to recuperate from civil war. Gbowee told me in 2012 that, nearly a decade after the fighting ended, the country remained devastated and divided, with “damaged people” living next door to people they had once fought. Some were former child soldiers stuck in poverty and despair; all were from different political groups and subgroups. At the time, the government had enlisted Gbowee to lead a reconciliation initiative, and she was visiting villages and talking with local leaders, women and girls. “I found that most people genuinely want to move on,” she said. “They want to reconcile.” To help provide the resources to do so, she founded the Gbowee Peace Foundation, which provides educational and leadership opportunities to women and children.

This year, she was named to the board of advisors of Seton Hall University’s School of Diplomacy, where she will serve as a visiting scholar during the coming academic year. At a university event, I asked her what she hopes to impart to American students. “I’m bringing the reality of life as it is in the peace and security world,” she said, noting that she hopes students “will come off different from a lot of the diplomats that we have in our world today.” She explained, “The real world is different from the theoretical world. The real world is not just about what we’ve seen over time — I can tell you what is happening in a village, something that you may not necessarily see on social media or in a textbook.”

She hopes students will come to see grassroots activists “as experts in their field, and not subjects of research,” she said. To illustrate her point, she tells a story: In 2010, a United Nations official called the Democratic Republic of the Congo “the rape capital of the world,” and the term swirled in the media. Soon afterward, Gbowee traveled to the country to work with women and asked them to name the biggest issue they faced. “Everyone said, ‘Women in power.’ Women in leadership was the number one issue. Most of the women said, ‘We have laws on rape. It’s just that we are not situated in a space and place where we can push for the implementation of these laws.’”

The experience served as a reminder to “take off our arrogant, intellectual hats,” Gbowee said. “It’s so easy for us to talk to some national expert, international expert, and decide that this is the issue that is confronting a group of people. I come from a community where I know that women at the ground level know exactly what they want.”

Abby Pesta, a former intern with this magazine, is author of The Girls: An All-American Town, a Predatory Doctor, and the Untold Story of the Gymnasts Who Brought Him Down (Seal, 2019) and co-author of How Dare the Sun Rise: Memoirs of a War Child (Katherine Tegen Books, 2017).