Barbara Johnston

Barbara Johnston

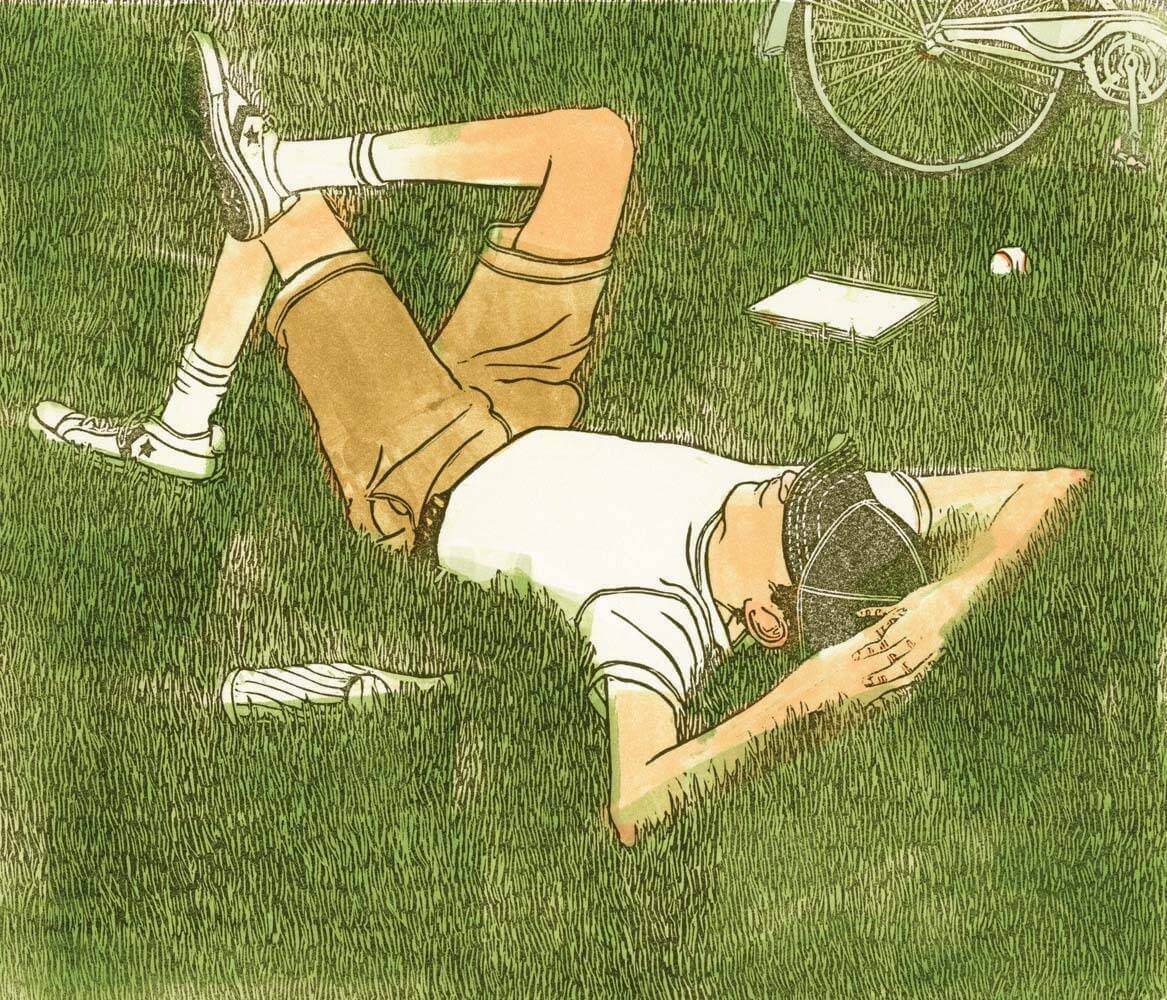

Kerry Temple ’74 retired as editor in January after 28 years sitting in this magazine’s top chair and 43 as a member of its staff.

Succeeding his great friend and mentor Walt Collins ’51, Kerry inherited a legacy stretching back to the likes of Dick Conklin ’59M.A., and founding editor Ron Parent ’74M.A. — and, from the days before Notre Dame Magazine, such gifted and undersung progenitors as Tom Stritch ’34, ’35M.A., Richard Sullivan ’30 and Ed Fischer ’37. As editor, Kerry extended a great Notre Dame tradition: a deep belief in the alchemical power of the word to address the world’s mysteries, failures and hopes, and to prompt new resolve in reader’s hearts and minds. He also produced several volumes’ worth of world-class nonfiction writing — expressions of his poetic heart and a probative mind given to curiosity without judgment.

No doubt Kerry, the antithesis of the rah-rah Notre Dame man, is rolling his eyes at being placed upon a pedestal. The fact remains he was a champion of what he took to be the highest ideals of Notre Dame and its people: authentic humility, service to the downtrodden, hope for humanity and the planet, devotion to justice and hunger for peace.

To understand how well Kerry himself embodied those traits, read these tributes — a representative but only partial sample — from magazine contributors, colleagues and other longtime friends. Find the full outpouring at magazine.nd.edu/kerrytemple.

The cumulative impact of Kerry’s counsel and craftsmanship chronicled here celebrates a humble man who spent his life’s work hunkered over words — and in that painstaking labor forged a legacy that will long resonate from these pages.

— the editors

Paths of discovery

As a writer still learning the ropes at age 69, I treasure the example Kerry has provided. In his own writings, he maintains a tone of discovering, not judging. This is what he saw. This is what it may mean. What do I think about that?

A current mood in our world wants us to memorize and repeat doctrine, to avoid other paths that are open wide. Instead, Kerry leaves space for a reader like me to find my own footing.

This is a tone I see throughout the magazine he has guided. Writers of all sorts encounter eyewitnesses to life’s mysteries, near and far. Their testimonies are clearly stated, often nudging me to think about them long after my reading is done. The book doesn’t close.

His example reminds us writers that we all start with a blank page. Every word we put on it has kinfolk worth knowing as well.

— Ken Bradford ’76 is a former reporter and editor at the South Bend Tribune.

A human touch at the keyboard

Writing allows mediocre people who are patient and industrious to revise their stupidity, to edit themselves into something like intelligence. Paraphrased, that’s a Kurt Vonnegut quote that Kerry Temple shared with me on the first day of my internship at Notre Dame Magazine.

I don’t think Kerry was suggesting I was mediocre. Maybe I was, but he hardly knew me. I hadn’t even interviewed me for the role, as I lived in Europe until a few weeks before he shared that quote. But the insight helped me figure out what I would do at the magazine. And I think it’s a good way to look at Kerry, too. Not that he’s mediocre, either!

Kerry is, however, unassuming. His kindness shines through immediately, as is true of all the people with whom he has surrounded himself on the magazine staff. He doesn’t make you feel like he’s smarter than you, even though that may well be true. But when Kerry writes, I am completely enveloped (though sometimes I don’t automatically know what to take away from what he said — at least not consciously).

One story that comes to mind from time to time concerns foxes and a childhood friend who died much too young. On the surface, there was no connection between these two subjects, and the piece was really two stories under one headline. Seven years after it was published, I think about how Kerry ended a paragraph — and really, the story — with a one-word sentence: “Fox.” (You can’t do that, Kerry.) Yet, in doing so, he somehow pulled the two stories together.

Before I met Kerry, I wouldn’t have seen the point of writing like that. Or even on such topics. I wouldn’t have worried about what Kurt Vonnegut had to say, because I was a facts-first reporter who happened to use writing as a medium. Kerry wrote about seeing a fox he can’t say for sure wasn’t make-believe.

He taught me that, if I give it enough time — it also helps to have a good editor, which Kerry is — even I can write something that may not matter in the fast-paced news cycle but matters to being human. Or, as is often true for Kerry’s writing, to the soul of a university.

— Rasmus S. Jorgensen is a reporter for Missouri Lawyers Media.

The maestro

Not to get too grand about this or anything, but I owe my professional life to Kerry Temple.

As a writing teacher, he turned a nascent interest into a full-blown ambition, embodying the fun and fulfillment — and never denying the frustrations — of working with words and ideas.

As a mentor, he heard me out over hand-wringing and venting lunches, offering wise reassurance, and he put in a good word on my behalf whenever I needed it.

As an editor, he nurtured my work and tolerated my hang-ups with compassion, even commiseration, as if our conversations about this maddening craft were between equals.

I can tell you that he did all these things and much more as maestro of Notre Dame Magazine for more than half of its existence. The weird thing is, I can’t tell you how.

Not one for trendy jargon or — shudder — branding, Kerry espouses no philosophy, attaches no particular significance to his way of doing things. His easygoing modesty belies his stature in the eyes of his staff, colleagues across campus, and fellow writers and editors. If he were forced to absorb all this praise out loud, he would literally start sweating from embarrassment.

Since I started working here, witnessing Kerry’s deft assembly of each issue has not cleared up the mystery of how he does it. As I write this, the editors are reviewing proofs, the last chance to catch any mistakes before they’re printed for posterity. For me, proofing also offers an opportunity to marvel at Kerry the composer, arranger and conductor.

The three-month production process can be cacophonous. Some ideas develop; some dissipate. A few writers meet deadlines; others are deadbeats (guilty). Each story undergoes fine-tuning to hit just the right tone and harmonize with the others. And every feature includes grace notes in Kerry’s own (uncredited) words, such as a headline that evokes and elevates, a masterful use of the form that another editor once described as a cross between poetry and a crossword puzzle.

With the lightest touch on the baton, he brings melodious order to the commotion of magazine-making. When it’s all printed and bound and mailed, and he should take a bow, he instead sweeps his hands toward the orchestra.

Kerry kept his impending retirement as quiet as he could, but he had to endure a few rounds of applause. At the official farewell reception that he needed goading to agree to, he asked to turn down the heat in the room to stop the sweat trickling at his temples.

Tributes are not his thing. He believes, in all sincerity, that the compliments are hyperbolic and, anyway, beside the point. What’s on the page is what matters to him. That, and fantasy baseball.

I haven’t even talked about his writing. Most Notre Dame Magazine readers recognize that aspect of his work, if not the behind-the-scenes subtleties of editing.

In one recent literary magic trick, Kerry wrote about . . . things, which sounds like a parody of a story idea. To do it in earnest is the writing equivalent of that guy who walked a tightrope between the World Trade Center towers.

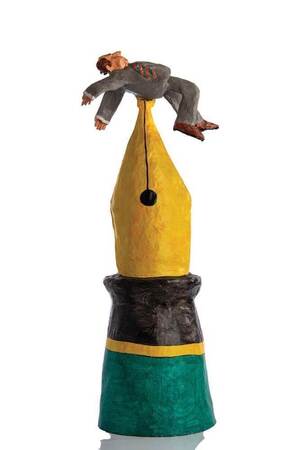

The inspiration was this thing: a paper-mache sculpture of a man impaled on a fountain pen, Kerry’s thoughts unspooling from there into a mediation on the meaning of objects and the memories they conjure. A friend of mine told me that essay made him cry.

I’ve known Kerry for more than 30 years. He’s taught me more than I could quantify. But that? There are, ironically enough, no words to describe that.

— Jason Kelly ’95 is editor of this magazine.

About people at heart

As I set out to write this, on a gray morning in late September, the days winding down toward something I really don’t want to think about, Kerry Temple is still within my field of vision. He’s sitting right over there — maybe 50 feet away? — huddled over his keyboard, tapping out a message to someone, or maybe savoring a story idea about which he hasn’t let on yet.

People walk in and out of his small, glass-walled office maybe a dozen times a day. A joke floated around a few years ago about Kerry needing to make himself more approachable. Some joke. I see a man who readily sets things aside for the personal encounter, who considers quickly but carefully whether to take a phone call that would interrupt your conversation before picking up. Whatever he’s thinking about — and what hasn’t he thought about? — whatever’s on his mind, light or heavy, some wonderment or some tedious administrative obligation, his eyes brighten in the presence of other human beings. Near-always with warmth and welcome, often with humor, often with a fleet meditation he might or might not share, unfailingly with respect, with genuine consideration. Even when you’re not exactly the first person he’d hoped to see.

See, as much as he loves the words and ideas, the stories and memories, this work of writing and editing Notre Dame Magazine has for Kerry always been about people. I’m pretty sure that’s his secret.

It’s reassuring to see him in that office, to expect his next editor’s column, to anticipate a promised Kerry Temple feature that might nominally contemplate the sun or the earth or baseball cards or his students, but which is always, always about the workings of the human heart. It’s reassuring to watch that creative vision unfold from one issue to the next, to climb aboard the toy train of some iridescent idea he’s announced with boyish awe and curiosity, banging the drums of his staff’s enthusiasms, and to see where the fool thing is chugging off to, certain it’ll be more than worth the trip.

Never once in my 17 years working for Kerry has the coalbox of that creative engine gone cold. Quite the contrary. Throw a global pandemic and lockdown at him and you’d get the South Bend issue: more writers, more reporting, more stories, more pages, more moving pieces, more fun and more good writing than we’d ever offered readers before. I thought he was crazy — and he was — but he was also clear-eyed from Day 1. And he was right.

The world needs hope? Goodness? Silver linings threading upward through the gloom? How many times did Kerry feel it six months ahead of time, delivering just as the rest of us needed it most?

Above all, it's reassuring to know Kerry will read your flailing prose before anyone else does, to know he’ll know how to help you catch the wind just right so your kite can fly, worthy now of the eyes and time of everyone else.

If you’ve met him, if you’ve talked to him, if you’ve written for him, if you’ve read him, you know what I mean. But if you still think it’s about the words, I understand. He doesn’t write beautifully. He writes beauty. He writes like he’s talking to you and never hits a wrong note. Just incredible. He wrote, about foxes, to take one instance from a thousand:

I stood there for a while, knowing they were gone, said a prayer of gratitude, and turned to head back home. Then noticed, under the streetlamp down the hill and maybe 20 yards away, one of the two had stopped and looked back at me. It was a mere silhouette in the light-glow, but it stood there for a while, sort of taking me in — a pause in the cosmos, a moment in time, a look across borders between this world and that. Fox.

But now read what he wrote about Dick Conklin ’59M.A. or Jim Frick ’51, ’72Ph.D. or Tom Suddes ’71 or Jim Gibbons ’53 — each one a Notre Dame giant for whom Kerry felt immense gratitude and to whom he has bid farewell in these pages. Read one of his Thanksgiving thank-yous to his Notre Dame professors or his basketball coach in Shreveport, or to Mr. Burke, the high school English teacher who, in a moment most of us would have mistakenly brushed over, gave Kerry a gift of soul he never forgot.

Read Kerry’s story about being Father Ted Hesburgh’s driver on a daytrip into Amish country, a tribute that soars above all the others. Then you tell me what Kerry is about.

Now, as he retires, Kerry deserves a Kerry Temple to write about him. He gets all of us, doing our best, groping in search of words that capture one facet or another of this quiet, good-hearted, generous man who yet has so much to say, ever a story to tell. And every word speaks gratitude, gratitude, gratitude.

— John Nagy ’00M.A. is managing editor of this magazine.

He made you wonder

Sleep on the hard ground. Pee in the woods. Haul a heavy backpack wherever you go. Swat those pesky mosquitoes. And always keep watch for nature’s less friendly fauna.

Backcountry hiking — Kerry Temple’s dream vacation.

I am not averse to outdoor fun, and except for being swarmed by black flies at a campsite in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, I’ve enjoyed tent camping at several state parks. But days of trekking on nature’s pathways, despite the majesty waiting to be discovered, isn’t for me.

When Kerry writes about his travels through the natural world, however, I shake my head in wonder. An impeccable wordsmith, he can turn a glimpse of a patch of poison ivy or an algae-encrusted pond or a sneaky slithering snake into a lyrical musing on God’s sometimes peculiar glory.

One walk through the woods by Saint Mary’s College, for instance, evoked this remembrance:

In the quiet here I have listened to the air rushing through the wings of geese, have watched the stilt-legged blue herons sniping fish in the shallows along the riverbank, and have learned that each twilight sky is a singular expression of light and life, of cloudscape and sun. I’ve come to appreciate the little things here — the blaze of a cardinal against the blue-white of a winter day, the smell of the earth after a summer rain, the nervous irascibility of opossums.

Through his years at Notre Dame Magazine, when he returned to his workaday cubicle after a trip to the Southwest, Kerry continued to mine his trailside wanderings for essays about how the lure and lore of nature called forth such disparate recollections as a pickup basketball game, a march across the Arctic, or a childhood afternoon playing with plastic soldiers.

It’s difficult to predict where the paths he traverses might lead, but it is always a joy to roam with him. Although Kerry’s speech patterns don’t reveal his Shreveport, Louisiana, roots, his essays announce a person rooted in nature, a man who cherishes what God has provided.

And sometimes, his philosophical reflections can elicit a quiet tear, a reminder of life’s bittersweet promises, a sigh of acceptance:

I would like to die outdoors. I would like to die with the sun on my face — the way it feels at the moment its warmth takes you by surprise, coming from far away, and you shut your eyes and lift your face to catch the sunbeams finding you. A touch of gentle heat, a warm wash of sunlight on your upturned face. A cosmic anointing.

Kerry and I are both of an age when that cosmic anointing no longer seems remote. And yet, his gentle writings soothe my soul.

— Carol Schaal ’91M.A. wrote and edited at this magazine from 1986 to 2017.

A talented and steady hand

I’ve often said over the past three decades that Kerry is arguably the very best writer at Notre Dame. I say “arguably,” because I also have worked closely with Denny Moore ’70 and Mike Garvey ’74, superb writers in their own right. All three have combined a wonderful way with words, a careful editing eye, and deep knowledge of and appreciation for Notre Dame.

I also have often said that Notre Dame Magazine is — no argument — the very best publication in higher education. That speaks to not just Kerry’s editorial prowess but to his managing skills as well.

We have been fortunate to have such a talented and steady hand on what I consider our finest communications channel, and we will miss all he has brought to his alma mater.

— Dennis Brown is assistant vice president for issues management at Notre Dame

A publisher of writers

Kerry Temple was not just the great editor of Notre Dame Magazine, but its publisher. And, as was said of the great publisher A.S. Frere, Kerry didn’t publish articles, he published writers. They became his friends and rigorous intellectual compatriots.

In his dedication to The Comedians, Graham Greene wrote of Frere as many thought of Kerry: “When you were the head of a great publishing firm I was one of your most devoted authors, and, when you ceased to be a publisher, I, like many other writers on your list, felt it was time to find another home. This is the first novel I have written since then, and I want to offer it to you after more than thirty years of association — a cold word to represent all the advice (which you never expected me to take), all the encouragement (which you never realized I needed), all the affection and fun of the years we shared.”

— Paul Browne retired in 2021 as vice president for public affairs and communications at Notre Dame.

Heartfelt gratitude

Dear Kerry,

I join my sincere and heartfelt gratitude to many other people’s to thank you and to wish you the very best as you begin a new chapter of your life.

You have and will always have my utmost gratitude for encouraging me to write. I am grateful to you beyond words.

I want to wish you the very best as you prepare for this next chapter in your life. Who knows where God will take you and what God will do with you? One thing for sure: God will accompany you every step of the way. The same God who brought you to Notre Dame Magazine many years ago will accompany you in the next stage of your life.

You have helped to make Notre Dame known all over the world. I constantly run into people who reference this article or that story that they read in the magazine. You have truly advanced the mission of Notre Dame.

My encounters with you over the years have been filled with grace. Thank you, Jesus. Thank you, Kerry.

May God bless you and keep you today and always.

— Rev. Joseph V. Corpora, CSC, ’76, ’83 M.Div., is associate director of the Transformational Leaders Program at Notre Dame and a frequent contributor to this magazine.

Intelligence, curiosity, warmth, wit, humanity

A few years back, one of my students wrote a beautiful essay for my University Seminar class. On a whim, I sent it to Notre Dame Magazine. I had no expectations it would be published, or even that I would hear back. I had received enough rejections of my own writing to know that editors were busy people — and not always the nurturing type.

To my surprise, I heard back from the editor, a man named Kerry Temple, that same day. Even more surprising, he wrote a wonderfully gracious note saying how much he liked the essay and that he wished to publish it. (“After some editing.” He is an editor, after all.) I was delighted, and my student was even more so.

What I eventually learned about Kerry was how committed he is not only to good writing, but how committed he is to supporting student writers. I’ve since sent many students’ essays to Kerry, and while he hasn’t published them all, I know he’s read them carefully and generously.

Kerry’s commitment to student voices is evident in pieces he has published such as “The Personal Essay: In which Gen Z students reveal what’s on their minds” and “What Gen Z Students Want Us to Know About their Lives.” Although I have been teaching at Notre Dame for more than two decades, I was surprised by how much I learned about young people from the pieces Kerry published.

But it’s not only his support of student writing that has made Notre Dame Magazine such a special publication. Essays, articles and interviews over the years on such diverse topics as the virtue of hope, the future of Ukraine and the history of women at Notre Dame tell us about the University today, its values and commitments, and where it might lead in the years ahead.

Since that first email years ago, I’ve had the pleasure of meeting Kerry several times. The man I’ve met demonstrates the same qualities consistently found in the pages of Notre Dame Magazine: intelligence, curiosity, warmth, wit and humanity.

Thank you, Kerry Temple, for all your good work. I am a better person for what I’ve read in Notre Dame Magazine, and I know I’m not alone.

— John Duffy is the William T. and Helen Kuhn Carey professor of modern communication in the Department of English.

Love in the writer, love in the reader

Dear Kerry,

Please allow me to join your many colleagues, friends and admirers in thanking you for your leadership and dedication over 28 years as editor of Notre Dame Magazine.

I am deeply grateful to you for sharing your extraordinary gifts as a writer to tell the stories of the Notre Dame family so beautifully, and for making it possible through the magazine for countless other writers to do the same. Like any family, our stories bind us together, and I thank you for what you have done to connect us. To paraphrase Robert Frost, no love in the writer, no love in the reader — as a leader and as a writer, your love and devotion to Notre Dame have always been evident. Thanks for sharing your passion for Notre Dame with the rest of us, and for being such an important part of the place over these many years. You’ve been a great colleague to me and many others.

I wish you the very best as you begin what I hope will be a wonderful new chapter, Kerry. Know that you and your family are always in my prayers.

— Rev. John I. Jenkins, CSC,’76,’78M.A., is the 17th president of the University of Notre Dame.

Thanks for the adventures

Full Circle Organic Farm in Howell, Michigan, on a bitterly cold day in February. I was tasked to photograph the owner, SuzAnne Akhavan-Tafti ’91M.A., performing some of her daily tasks at the farm where she raises grass-fed lambs. Typically, when a photographer wants to include an animal in a portrait, the animals never cooperate, but in this case, Baby, a 5-year-old wether that had earned permanent residency at the farm, looked directly at the camera right on cue in the first frame with SuzAnne. The portrait appeared on the cover of the spring issue of 2017.

Kerry, thank you for all the wonderful adventures and interesting people I met over the years while on assignment for your incredible magazine. Enjoy retirement!

— Barbara Johnston is a University photographer.

Delight in ideas

Twenty-eight years. Four issues a year plus two more thrown in. That’s 114 issues. Each issue composed of an editor’s column, dozens of news items, detailed alumni notes from almost every class, short essays, long essays and photography. The digital era meant new forms: a website, a blog (when those were a thing), a Twitter feed (still sort of a thing) and a Facebook presence (a thing for more, ahem, seasoned alumni.)

To do this writing and editing is a vocational choice. Kerry would not put it that way; he suspects easy certainties. But he delights in big ideas, even, as he put it occasionally, “juicy” controversies. He recruited the best authors he could find. He persuaded them to tackle in an unhurried and beautifully illustrated way topics such as the existence of God (good luck finding that theme in another alumni publication), the meaning of one’s hometown and polarization in the United States. When the magazine pondered the fate of the Catholic Church, as it often did, Kerry knew the letters to the editor in the next issue would reveal fissures within Notre Dame’s community that benefited from scrutiny. When he commissioned a lighthearted fashion issue, he understood that he would thrill and amuse many readers while infuriating a few others.

In part, Kerry’s achievement is to have elevated the genre of the alumni magazine. This is not a controversial claim. It is a consensus view, as indicated by the many awards received by Kerry, his colleagues and the magazine’s writers.

The more subtle achievement is to have enriched the community that he made his own. It’s not an achievement he could have imagined when he showed up in South Bend from Louisiana in the fall of 1970 with a hazy idea that he might study literature. Or even when he returned to work at Notre Dame Magazine. Over time, though, he made Notre Dame and its 150,000 alumni more cognizant of their evolving alma mater and more informed about the lives their classmates led and the world they inhabited. How lucky we are that he committed himself to this work, and that he did it so long and so well.

— John McGreevy ’86 is the Charles and Jill Fischer provost and Francis A. McAnaney professor of history at Notre Dame

A Godsend to Notre Dame

Kerry, you have been nothing short of a Godsend to Notre Dame. Your leadership of Notre Dame Magazine for almost three decades has been a ton of work made to look effortless. You have managed brilliantly the delicate balance of editing a University publication while welcoming a free, dynamic range of discussion around important issues.

Thank you for being such a good friend and wonderful colleague over the years. Proud to have labored in the trenches with you along the way. Prayers and best wishes for you and your family as you move on to this next stage in your life. I look forward to reading new works from you in the years ahead.

— Lou Nanni ’84, ’88M.A., is vice president of University relations at Notre Dame.

The editorial diplomat

On the too-rare occasions when I saw Kerry Temple on campus, my soul felt a little more settled. Kerry invariably exudes collegial warmth, graciousness and optimism, his humor is dry and sometimes delightfully subversive. Perhaps because he’s a writer himself — a fine, lyrical writer — he has a wonderful feel for other writers’ doubts and insecurities. Crossing his path over the years sometimes felt like an affirmation of the choice to teach at Notre Dame and sometimes like an affirmation of writing itself.

Kerry was kind enough to invite me out to lunch when I arrived at Notre Dame. I told him I was impressed with his magazine, especially with the way it balanced what sometimes looked like dueling objectives: raising communal spirits, celebrating success and gently pricking consciences. Notre Dame Magazine covered controversies and paid attention to student voices, past and present, not necessarily in the mainstream. I wondered if that ever brought him grief. This might have been the most gauche question ever posed at a campus lunch, but Kerry laughed. He allowed that he’d been called into certain administrative offices to explain himself, but said this with the kind of rueful good humor that helps explain why he’s been so successful for so many years at a job requiring the diplomatic skills of a papal nuncio.

Kerry wondered whether I’d be interested in being on an advisory board that could offer counsel about the tough editorial calls he had to make, but, recognizing my own tendency to run headlong into controversy, I declined, genuinely concerned that I’d land him in more administrative offices. When he suggested story ideas, I turned him down, too, though my reasons for that were more selfish. Kerry never pushed. He doubtless recognized a writer who, like many other writers, dreads writing. He took my excuses about having my hands full with student manuscripts and book reviews and a graduate program with his usual good grace.

It moved me that Kerry simply overlooked all the times I said no, that he kept coming at me with more ideas until one clicked. He revealed himself to be a dream editor: the one who reads the essay the day it’s submitted and sends a note so appreciative, so tuned in to what the piece is attempting, that the essayist’s characteristic pessimism fades away in favor of delight in a written conversation with a much-admired fellow writer.

Kerry’s own writing, after all, does the kind of deep soul-searching that all serious writers go for. His book, Back to Earth: A Backpacker’s Journey into Self and Soul, is written in the kind of lucid, limpid prose that eases a reader into the toughest existential questions. His appreciations of the natural world are as detailed and as particular as his magazine’s descriptions of the intellectual and social worlds of a university. That he is a practicing essayist who elevates the genre, who takes delight in pattern and wit and musical language — even when he’s simply writing the introduction to the current issue — makes him a joy to work with.

Time now for a backpacker’s journey into retirement — though, as every editor knows, there’s no such thing for a writer. May this time away from the office offer Kerry Temple as many hours as he’s inclined to fill writing his own beautiful prose. It’s hard to imagine Notre Dame or NDM without him, but here’s hoping that, like so many other alumni, he comes back often, especially in the pages of the magazine.

— Valerie Sayers, author of six novels and a collection of stories, is professor emerita of English at Notre Dame.

A literary triple threat

Now that Kerry Temple is removing his green eyeshade and retiring his blue editing pencil, he’ll no doubt be red-hot to devote more time to doing what he does so well. No, not competing in Ironman triathlons, but composing essays that bear the unmistakable hallmarks of experience recollected with sensitivity and style.

As his Notre Dame years have proven, Kerry is a rarity: a literary triple threat. He’s an exacting editor with astute suggestions for improving a story, a compelling writer adept at making sentences sing and dance, and a committed teacher instructing young wordsmiths in the classroom and during internships.

Who among contributors to Notre Dame Magazine since 1995 isn’t in Kerry’s debt? Who among his readers hasn’t finished one of his essays with uncommon appreciation for his prose and personal perspective?

For many people, retirement can be similar to an academic commencement. New doors open as older ones close. Let’s hope for Kerry that future doors lead to places he wants to go and to subjects he wants to probe — as only he can.

— Robert Schmuhl ’70 is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce professor emeritus of American studies and journalism whose many books include The Glory and the Burden: The American Presidency from the New Deal to the Present.

Tuesdays with Kerry

The last thing in the world Kerry Temple would do is call attention to himself. At a meeting with his division colleagues in 2002, where folks were asked to introduce themselves to a new boss, Kerry simply said, “I’m Kerry. I do the magazine.”

And oh, how he has done it. Notre Dame Magazine is a gem, an eclectic and elegant quarterly that says, “We’re not just about university news and personnel, we’re a window into the diversity of thought and experience that represents a community of excellence.”

Then there’s Kerry the writer. There are undoubtedly other university magazine editors who oversee great publications, but I doubt there’s one who’s a more thoughtful, even lyrical, writer. He writes about nature, his great love and solace, and he writes about values and people he admires. And here’s an irony: Though privately he can complain about some of his Notre Dame experiences — typical of almost any employee or student — no one has written more evocatively of the place. His books with photographer Matt Cashore ’94 (Celebrating Notre Dame, 2007 and This Place Called Notre Dame, 2018) are brilliant keepsakes.

Writing in a commemorative issue after the death of Father Ted Hesburgh, Kerry said, “Hesburgh left his mark on the world, Our Lady’s University, the people whose lives he touched in big and little ways. We’ll all miss him. But we’re also now obligated to carry on, to move forward in the ways he showed.”

His writing and editing are his public face. I also had the pleasure, during the dozen years I worked at Notre Dame, of knowing the very personal side of this quite private man. He would probably prefer to be alone with his thoughts most of the time, maybe while backpacking in the Bighorns of Wyoming, and he is even reluctant to shake hands. (I never tried.) But to my good fortune, we had a standing date for lunch every Tuesday. Those were some of the best conversations I’ve ever had. I honored him with my most personal thoughts, and he did likewise. Tuesdays with Kerry were the best of times.

As important as the magazine is to his life, and as much as he loves solitude, nothing compares to the time he can spend with family. A lot of those intimate conversations were about those most important people in his life. So, while the triplets are now off to college, I know the coming years will be centered around those relationships. A child could hardly do better than having Kerry Temple for a dad. And anyone would be hard pressed to find a better friend, handshakes or not.

Building on the work of predecessors Ron Parent ’74M.A. and Walt Collins ’51, Kerry shepherded a delightful and serious magazine. It brilliantly provides Notre Dame’s face to the outside world (other than football). He has fought vigorously to prevent its becoming a house organ or public relations vehicle, and by that very effort has brought more credit to Notre Dame.

After writing an story for the magazine in 2006, I was surprised to find that David Broder of The Washington Post, the late dean of American political writers, was a faithful reader. And it is not unusual to hear from someone who never set foot on campus that they love the magazine.

I’m sure his colleagues will miss his leadership. To paraphrase Kerry, they’re now obligated to carry on, to move forward in the ways he showed.

— Matthew V. Storin ’64 was editor of The Boston Globe from 1993 to 2001, then taught journalism at Notre Dame and served two stints as associate vice president for communications.

A quarterly reminder of our family connection

Receiving Notre Dame Magazine each season elicits in me a bit of pride as well as a sense of obligation I feel as a Notre Dame alumna. The magazine’s conversations can be challenging, and the letters to the editor are sometimes contentious. But just as the content is interspersed with photographs of a beloved place, so the discussions seem ones that might occur over a dining hall meal and the disagreements like those between dormmates. I usually find the most inspiring stories to be ones highlighting unsung heroes who use their gifts in service to others. Thank you, Kerry, for providing a magazine that sings their songs. Thank you for using your gifts to serve Notre Dame and for the quarterly, tangible reminders that each one of us is part of this family.

— Erin Buckley ’08 has written the back-page essays in each issue of Notre Dame Magazine since Winter 2021-22.

From contention to conversation

The fact that my writing ever graced the pages of Notre Dame Magazine is something of a miracle, as my first contributions came when I was 22 years old and wanted to tell the editor he was WRONG.

I was a senior in college then — confident in my opinions, it goes without saying. So, I thought I was furthering the conversation when I read a given issue, fired up a computer in the Fitzpatrick lab, and complained via sloppy emails which articles were too doctrinaire, too safe, too committed to the status quo.

Looking back, it was a perfect recipe for getting relegated to the spam bin. But Kerry took my ungracious criticism and somehow transmuted it into encouragement. “It’s interesting you think that,” he’d say. “Have you considered this? Why don’t you think some more about it, see if you want to write something?”

I’m so grateful he didn’t just blow me off. I’m sure it helped that we knew each other slightly. I grew up in the same neighborhood as his older sons; I was his paperboy when I was younger. We competed in fantasy baseball and basketball, which introduced me to Kerry’s workhorse ethic and unassuming drive to do things at their best. At Notre Dame, I did well in school but wasn’t sure what I wanted to do in life. I thought, vaguely, I might want to be a writer, and Kerry’s kindness was a lifeline.

That gentle support is the backbone of Notre Dame Magazine. A writer has to feel safe to reveal something true about himself and the world around him. Think of the stories that have stuck with you. Parents losing children. Children losing parents. Near-saints caring for orphans in tragedy-stricken Haiti. Watching a game of pick-up basketball with your brother, knowing it might be the last time you get to do so.

Kerry’s grace made that happen. It made things happen for me, too, even if my contributions tended toward the lighter end of the spectrum: hearing live music or buying a skateboard to push my way through the pandemic and the onset of middle age.

With the magazine, Kerry created a refuge for people to thoughtfully explore what’s happened to them, what they value and how they’ve chosen to live their lives. Sadly, spaces like these are increasingly rare. It’s to the credit of the University that it has supported the magazine as well as it has. The stories we’ve seen in these pages — deep reflection blended with higher purpose — embody the values of Notre Dame. Each issue offers a little boost for our community, inoculating us with the feeling of being on campus, especially if it’s been too long since we last visited.

As Kerry heads into retirement, I imagine he’ll be happy not to get any more letters telling him everything he’s doing wrong. (I do worry this unburdening might turbocharge his fantasy sports prep.) But he might miss those letters, too. The feedback — the good stuff, at least — is part of a grand conversation he’s guided artfully for decades now. I only hope he continues to contribute, even as he moves to a different space at the table.

— James Seidler ’02 lives and writes in Munster, Indiana.

We reaped what he sowed

Into a dancer you have grown

From a seed somebody else has thrown

Go on ahead and throw some seeds of your own

These are Jackson Browne’s lyrics, recently shared in Notre Dame Magazine by Kerry Temple — a man who for decades has thrown us seeds to pick up, plant, nurture and harvest in our own lives and the lives of others.

Years ago, I contacted Kerry to consider a follow-up to a short piece the magazine had published chronicling an alumnus who was working with HIV/AIDS-impacted children in southern Africa. Kerry demurred, as follow-up stories were not routinely in the mission of the magazine. However, a seed sprouted in Kerry’s abundant spirit, and soon Notre Dame’s exceptional photographer, Matt Cashore ’94, traveled to Lesotho to create a spectacular photo essay that nurtured the growth of the Tiny Lives Foundation. Today over 5,000 infants, children and mothers have received lifesaving nutrition, medication, housing and education from Tiny Lives. That seed, thrown by Kerry, continues to grow.

In 2010, a massive earthquake struck Haiti, and in those days of devastation Kerry planted another seed by asking then-associate editor John Nagy ’00M.A. and Matt Cashore to join a group of alumni who were flying to Haiti to create a mobile surgery unit. John and Matt dove into their work, inspired to capture the moments of pain, hope, fortitude, loss and resilience among the Haitian people. Their articles and photos planted more seeds leading to additional surgical and medical aid, to faculty and students researching the damage and designing affordable, quake-proof housing, to enhanced medical care for patients with lymphatic filariasis, and more. All “from a seed somebody else has thrown.”

And somewhere between the time you arrive

And the time you go

May lie a reason you were alive

That you’ll never know

We do know some of the reasons Kerry has blessed our lives over these years, reasons that extend far beyond being an eloquent writer and visionary editor: To nurture our insight into the diverse lives of others. To stimulate serious and compassionate thought. To discover our own enlightened, balanced perspectives in a polarized world. To be a humanitarian and plant the seeds in our world that can make a difference.

Kerry, we are all deeply grateful for your transcendent leadership of the magazine So much more than you’ll ever know.

Keep a fire burning in your eye

Pay attention to the open sky

You never know what will be coming down

Thank you for keeping that fire burning in my eyes as I took each new issue out to the porch, coffee in hand, ready for its challenge to pay attention to my open sky — that expanse of heartaches, blessings and mysteries. Indeed, while none of us know what’s to come, I thank you for the fire that always burnt in your eyes and inspired all the writers and readers you enriched. And for all the seeds you threw.

— Daniel J. Towle ’77 is a retired pediatric anesthesiologist who lives in Kansas.

A beneficiary of his personal gifts

Whenever I’m confronted with some petty work grievance — which is, in short, often — I think of how lucky I was to have had Kerry Temple as one of my first bosses. Kerry’s gifts as a writer and editor were among the blessings of working for the magazine: getting to hone my craft under the guidance of such a master of it. But I feel most fortunate to have been a beneficiary of Kerry’s personal gifts.

I was told repeatedly at The New York Times that the best journalists are good at journalism but bad at managing people, and that employees should simply expect bad management because of that. This dictum could not have been further from the situation at Notre Dame Magazine. Kerry not only helped me improve my writing, he not only gave me generous freedom to pursue new and interesting projects, but he treated me as a person first, rather than an employee or even as a journalist. When my boyfriend moved to Chicago, Kerry let me leave early on Fridays to catch the train to the city for weekend visits. When sad or exciting or quirky things happened in my family life, Kerry opened his office door to let me talk through them for as long as I wished. When I asked if I could use some vacation days to be with a friend after her mother’s death, Kerry insisted I simply go, no vacation days required.

For these reasons and countless others, I am deeply grateful to have worked for Kerry Temple, and I can only hope that the next leader of the magazine has a fraction of the skills that Kerry does for both editing and humanity. I wish you the best of luck in retirement, Kerry — congratulations on an incredible career.

— Sarah Cahalan ’14 is a freelance writer (tk) and was an associate editor of this magazine from 2017 to 2019

Glad he did what he did

I first met Kerry Temple several decades ago when I was a student journalist looking to expand my experience into magazine writing. I landed a Notre Dame Magazine internship as a college senior. I couldn’t have asked for a more formative experience.

At the time, Kerry was the newest editor on the staff — responsible for writing and editing the campus news section. We talked about campus issues, discussed writing styles and exchanged Notre Dame history facts. He trusted me, a rookie, with several important reporting assignments. The magazine office — then located on the creaky fourth floor of the unrenovated Main Building — became a welcoming “third place” on my daily travels around campus.

I freelanced occasionally for the magazine during my subsequent years in newspaper journalism. Kerry knew my interests and recognized what topics were ideal assignments for me.

Fast forward a few decades, and I had come full circle. I was back at Notre Dame Magazine as an associate editor, planning and writing the campus news section — and continuing to learn lessons from Kerry Temple.

What will the magazine be like without Kerry’s daily presence? It’s difficult to fathom. My co-workers and I have never known the place without Kerry’s self-deprecating humor, deft talent with his editor’s pencil and regularly expressed thanks and appreciation. The quality content and reputation of the magazine are largely due to Kerry, the steady hand on the tiller all these years.

Kerry as a writer is gifted and eloquent. He makes it look easy. Kerry as an editor and a person is patient, thoughtful and encouraging. “I’m glad we do what we do,” he is fond of saying to the staff.

We’re glad, too. We’ll take all we’ve learned from Kerry over the years and continue to reach for the high standards he’s set as an editor, a mentor and a friend.

— Margaret Fosmoe ’85, a longtime reporter for the South Bend Tribune, has served as an associate editor of this magazine since she joined the staff in 2019.

Opening doors

I met Kerry Temple while still a sleep-deprived, overly caffeinated, sweatpants-clad undergrad at Notre Dame. He taught Magazine Writing in the journalism program, and it’s not an exaggeration to say it was by far the most pivotal class in my Notre Dame education.

Where many professors lectured or dictated, Kerry shared. He invited us into a world not just of writing, but of noticing, of pondering, of reading. That was lesson one: To be a great writer, one must read great writing. And that writing knew no bounds. He assigned Annie Dillard’s “The Death of a Moth.” Other weeks, he’d bring in a stack of magazines: Esquire, The Atlantic, Time, Vanity Fair. We crossed genres and media, reading things that interested us — or that didn’t but still offered lessons in prose, in poetry, in rhythm, in style. And while his classes were rife with lessons, Kerry didn’t instruct. He didn’t push for output or participation. He just opened doors and waited to see if we walked through them.

In my case, he opened a door to an internship at Notre Dame Magazine, and then, unusually, a door to a position as an associate editor at the magazine. My predecessor retired after 38 years there. I had a fresh Notre Dame diploma that hadn’t yet been framed. There were not-so-quiet whispers that I might not be old enough, mature enough, for the role. Kerry shushed them all. It was but one of the times that Kerry saw potential before anyone else did.

He did the same with the many unsolicited manuscripts we’d receive. Many of us were quick to wave them off. Kerry encouraged us to give the stories a first edit. Brush off some dust. Rework a little here or there. He was patient and optimistic and encouraging, and could often see a nugget of potential, of truth, of resonance, even those buried under poor grammar or haphazard storytelling, or yes, under inexperience and naivete. He championed those stories. And he championed the staff, too.

I got an itch to write about a chef, he told me to find one. I got an invitation to join a pilgrimage, he told me to pack a bag. I wrote about cowboys and cocktails, Shakespearean scholars and social media, brain injuries, the Chilean revolution. It was all not just approved but fueled by Kerry. Anytime I mentioned even a fledgling interest, he pushed me to follow the breadcrumbs and see where they led. There was no story too big or small, as long as wonder and curiosity was there.

I imagine that’s why Notre Dame Magazine has been so successful under his tenure. While other university magazines have shrunk, become pure institutional fodder, or disappeared entirely, Notre Dame Magazine remains a place of curiosity, even, or perhaps especially, when the stories aren’t overtly Notre Dame. Yes, some stories are meant to stir the nostalgia we love to feel, some are meant to update readers on the status of things at their beloved University, some feature fellow alumni taking unusual roads, but by and large the stories are meant to reawaken the curiosity we all felt at age 17 when the world was ours to be explored. The stories force us out of our silos and subject expertise, stretch our now rigid brains into seeing things from a new perspective, and make us pause, reflect, truly think. The stories encourage empathy, love, neighborliness, justice, fun, joy — sometimes all in one issue.

That’s because of Kerry.

In his years at the helm, Kerry embodied not just what Notre Dame was or what it is, but what it was meant to be, and then he pushed the writers at the magazine to convey that in their own ways. Those writers, me included, are beyond fortunate to have had a place where we could write creatively, unabashedly, truthfully and freely. Kerry gave us those opportunities, even going to bat for us, and for the magazine, when necessary.

Kerry once told me many essays get stronger if you take off the last paragraph or two when the author drones on. But he’s not editor anymore, so I’ll keep this one intact. Kerry has championed me as a writer, as an artist and as a person for more than a decade. He gave me tools. He gave me mentorship. He gave me confidence. Then he gave me wings to go write elsewhere. And he has done the same for hundreds of others. He’ll never take credit for any of it, but I hope he sees this open door to thanks, to admiration, to appreciation, and walks through it.

— Tara Hunt McMullen ’12 was an associate editor of this magazine from 2012 to 2015.

He won . . . eventually

On March 24, 2023, I received an email from Kerry that others might have found troubling, even worrying.

“Anytime ever in my life I felt optimistic, the reality sent me reeling,” he wrote to me morosely. “Again, thanks for paying attention.”

While others might have been tempted to call Kerry or someone close to him, I just smiled. Because I’d seen Kerry wrestle with this feeling that the universe is against him. It had been happening at about this same time of year for almost as long as I’ve known him. Which is getting close to 30 years.

He felt comfortable sharing his dread with me because Kerry is, like me, an idiot.

My friend was wallowing in pessimism because it was playoffs time in our fantasy basketball league, the South Bend League, and he was certain some cruel twist of fate was about to strike.

In his defense, this was not pessimism. This was realism.

Our league began in 2001, and pretty much every year Kerry’s team — Beans and Rice (a favorite meal) — had one of the best records heading into the playoffs. And every year he lost.

Three years previous, his team was undefeated, close to a lock for the rather ugly traveling trophy that is the only reward for our league’s champion. Then COVID-19 hit, forcing the cancellation of the rest of the NBA regular season. Because fantasy leagues are based on player statistics generated during the season when all players are in action, the termination put an end to the South Bend League season — and Kerry’s hopes.

Maybe in 2023 his luck would change. I hoped so. Eventually.

I say “eventually,” because I had my own hopes heading into the 2023 playoffs.

I’d won the championship several times, and that year I had the league’s best regular-season record. I am, if I may brag, something of a genius at snapping up emergent free-agent talent in the first days of a season. For years Kerry coveted my Gilbert Arenas.

I knew I could count on getting past the first round of the playoffs. By virtue of having the best regular-season record, I was matched against the team with the eighth-best record.

I was facing a statistically inferior team with an absentee owner. My opponent had stopped participating. His lineup included Cade Cunningham, who had been out with an injury since November. November. So, it would be my seven players against his six. I couldn’t lose.

I lost.

I lost because he had Nikola Jokić, the league’s reigning Most Valuable Player and the fantasy basketball equivalent of the sun. A 6-foot-11, 284-pound, Serbian-made scoring, rebounding and assisting machine, Jokić in a given week can have the statistical production of up to four ordinary players.

I still should have won. In fact, I would have won had Draymond Green, a good, playmaking center and hotheaded nitwit, not been assessed his 16th technical foul of the season, resulting in an immediate one-game suspension.

After being eliminated, I transferred my rooting interest to my star-crossed friend. But he was having none of it.

“I’ve given up on ever winning the playoffs — however strong my regular season is,” he wrote after I wished him luck and said maybe this would finally be his year.

In the next round Kerry avenged my loss to the Jokić leviathan. That put him into the finals, where he faced a perennial powerhouse, the team of our league commissioner.

The score was tight all week and it came down to the final minutes of the last day.

Kerry lost again.

I’m kidding. I wouldn’t have written all this without a happy ending, would I? He won by a score of 883.75-870.75.

I live in the Pacific time zone and before going to bed sent Kerry an email with the subject line, “Yay!” I wrote, “Wow, it was close, but you did it! Congratulations, champ.”

He replied the next morning.

“I looked just now and am totally stunned. I checked last night before the games were done — but it sure looked like Beans was totally done. And I felt like I sure deserved to lose — because of bad lineup decisions. I went to bed thinking I would have won had I stuck with the guys who got me there.

“I have been looking, double-checking . . . there must be some mistake. But your email confirms it. Hey, thanks for being supportive and talking with me through the past couple of weeks.”

Happy to do so, my friend. And happy to keep doing so. Because old fantasy team owners never die, they just keep searching for sleepers and wishing they had Jokić.

— Ed Cohen was an associate editor of this magazine from 1995 to 2006. He is director of communications and marketing at The National Judicial College.

Notes to a cherished friend

Dear Kerry,

I’ve done the math. We’ve been friends for 31 years. I tried crafting a story that eloquently captured the seasons of our friendship and the appreciation I have for you as a friend and a writer, but random, nonsequential memories of you kept popping into my head. So instead of an orderly essay, I decided to write a list of reasons I cherish our friendship — in no specific order:

1. One of the first times we met for coffee in the Huddle to discuss something I had written for your class, it was a steamy August day. You sat down, drenched, and started the conversation with “Hi. I sweat a lot. Don’t be offended,” and I responded, “I laugh a lot. Don’t be offended.” So, we had coffee, you sweated, I laughed. And neither of us was offended.

2. Back in the mid-’90s, you took my dog to be put down since I was too sad to do it and my husband was out of town and my then-toddler son didn’t understand. (Remember Kramer, the crazy, inbred Dalmatian?)

3. We had been friends for a decade before I started working at Notre Dame in 2003, and the first few times we ran into one another in the hall or the office kitchen, all either of us could do was laugh. I loved that.

4. The first time you asked me to write for the magazine, I was really excited. And really afraid to let you down. When we discussed the assignment, you remarked that I had “good instincts for writing profiles,” and that’s all it took for me to feel like a real writer. I’ll never forget the power of those words or your confidence in me.

5. When we first became friends, we both were in the midst of painful life transitions. But we laughed anyway and grew and learned. I’ll always remember that time in my life with deep appreciation for you.

6. When I was offered the job at the University of Chicago, I walked over to your office to tell you that I’d be leaving Notre Dame. You hugged me, congratulated me, and said it was a great move and the right thing to do. You knew by my demeanor that I was really sad about leaving my colleagues and the University I loved, so you added, “and we’ll still go to lunch.” That meant so much.

7. We still meet for lunch on occasion and are able to pick up as if no time has passed. Last time we had lunch, you mentioned that you were thinking about retirement. It didn’t seem real to me then, and I still have difficulty imagining Notre Dame Magazine without Kerry Temple. But I know it will continue to flourish, just as you will, my friend.

— Susan Mullen Guibert ’87, ’93MCA is managing director of marketing communications at Indiana University’s Lilly Family School of Philanthropy.

A name to remember

I remember it like yesterday: Dick Conklin ’59M.A., Notre Dame’s public relations director, my boss, told me that the University had just hired a new writer — and that he was good, very good!

The new writer’s name was Carey Kimble, and he would start working in about a month. I was ecstatic because I knew Carey Kimble. He was my classmate at Marquette University’s College of Journalism, and Carey was indeed very, very good. Not only that, he was a really great person, smart, funny in a soft-spoken way. In short, he was someone you’d enjoy working with, or working for. You’d want him as a friend because he’s fun and loyal and caring. Then, a month later, I met the new writer, Kerry Temple.

Fast forward to today. With the benefit of more than 40 years (yikes!) of hindsight knowing him, of working with him and for him, I can say Kerry exceeded my Carey expectations. He has been a great colleague, great boss and, above all, great friend. In my book, he deserves a statue on campus as much as any football or basketball coach. As editor of Notre Dame Magazine, he has been that important for the University. Although, knowing Kerry, he would never want that, and so I offer only heartfelt congratulations and thanks, my friend.

— John Monczunski was an associate editor of this magazine from 1973 to 2012.

Our navigator finally charts his own course

Soar free now, Kerry. You’ve fulfilled so many responsibilities for so long, and even while doing all that was required of you, you found a way between deadlines to inspire us with ideas heartfelt and mind-expanding, poignant and memorable.

What better team could one find themselves a part of? What better navigator to guide it through the years?

Thanks for being sensitive to our egos and for keeping the magazine a project where creativity was recognized and the fine craft of publishing an important magazine was always practiced.

There are other seasons ahead and good things on the horizon. When the winter thaw arrives in a few months, embrace the coming spring and savor the sunshine, anyplace you want to be. You’ll have much more time to hike a mountain trail, to read or write a good book.

— Don Nelson ’91MCA was the art director of this magazine from 1973 to 2010.

Lunches with a legend

In February 2012, a few weeks after I took the job at Notre Dame, I received a phone call from Kerry Temple, editor of Notre Dame Magazine.

We met a week later, and I learned that Kerry grew up in Shreveport, Louisiana — which happens to be the place of my birth. I had never met anyone else from Shreveport, and then I learned we were born in the same hospital. How crazy is that?

Before that meeting ended, we agreed to meet every Thursday for lunch — and we did.

Now, there have been some holidays when we didn’t meet for our Thursday lunch, and a few Thursdays when one of us was out of town or had a meeting he could not get out of, but we’ve had nearly 500 Thursday lunches over these past 12 years.

Our Thursday lunch location bounced from Legend’s to the Linebacker to Waka Dog Cafe to Taphouse on the Edge. What didn’t change was the wide range of our conversations. They always included stories about our wives, kids and grandkids, some stories about Notre Dame football, baseball, some former colleagues, et cetera.

And we shared our favorite Notre Dame stories — with me asking to use some of his for Notre Dame Day and Kerry asking to do the same with a few of mine for Notre Dame Magazine.

I learned that Kerry is a huge baseball fan, that Roberto Clemente is his favorite player and the Pittsburgh Pirates his favorite team. He even convinced me to join his fantasy baseball league.

I admit my favorite conversations with Kerry were about family: the baseball exploits of his sons Pike and Finn and how he shared in their highs and lows. And his daughter Kinsey’s decision to attend Indiana University, and the trips to Bloomington to drop off Kinsey and Finn and to Missouri to drop off Pike for their first days of college. Not a dry eye with Kerry.

We’ve had some great conversations about health issues, life after Notre Dame, the environment, some politics, Hesburgh, Brian Kelly, Marcus Freeman and so on. And we talked plenty about his love and passion for the magazine.

Kerry and his colleagues’ work is legendary. There’s not a better university magazine on the planet. In a world where censorship and being politically correct rules the day, Kerry has been able to keep Notre Dame Magazine out of that fray. It’s one of his greatest contributions to the University — and it’s a power he’s earned.

It’s sad to know that Kerry is walking away from a calling that has consumed his life for 30-plus years. We talked about it at lunch today — how much he’s going to miss working with his teammates putting out that next issue.

The University is going to miss the mind, passion and all that is Kerry Temple. If we had a Mount Irishmore for storytellers, his face would be out front, no debate. Kerry Temple is a Notre Dame legend.

I can never thank the Lady on the Dome enough for bringing Kerry into my life. I always look forward to Thursdays because it means I will spend time with my friend.

— Jim Small was associate vice president, storytelling and engagement, for University relations from 2012 to 2023.

What grew from our encounters

The chance to reflect on my collaboration with Kerry Temple tempers my sadness over his retirement just a tiny bit.

I first met Kerry in 2002, at the old Greenfields Café in Hesburgh Center. Professor Vincent DeSantis, the legendary history professor, had connected us. Vince had taken a proprietary interest in my writing about Catholic sisters and had called Kerry to tell him he should publish an essay of mine on the subject. Kerry, ever-obliging, invited me for coffee to talk it over. I was very pregnant, so I helped myself to decaf. But I was also very, very tired, so I snuck in a splash of the real stuff, figuring it couldn’t hurt the baby too much. Kerry got a kick out of that, and we laughed. We became friends right then, and became better friends over the next 20 years, through that first article and many others since.

I didn’t write for the magazine as often as either of us would have liked, but Kerry was always gracious and understanding when a book deadline or another baby prompted me to say no to whatever he was pitching. In 2007, I published a short piece on the canonization of Mother Theodore Guerin, and I became so interested in that subject that when Brother Andre Bessette’s canonization was announced for October 2010, I had the idea that Notre Dame Magazine should send me to cover it. When I called Kerry, he explained that the magazine couldn’t exactly finance a trip for an aspiring Vatican correspondent. But, he said, maybe I could travel there on my own and write about it. (He reminded me that the magazine paid handsomely and that I could surely write enough words to break even.) I had the most wonderful experience at that canonization as a pilgrim and a historian, and I poured my heart into the article. It’s still a favorite of my publications. I remember how thrilled I was when that winter issue arrived and I saw that my essay was the cover story. (Full disclosure: It was on the back cover, which had a beautiful photograph of the canonization. But still).

My Brother Andre article contained the seeds of a book I would publish nine years later, and I am again using my most recent contribution to conceptualize a book project. The way that article came to into being says a lot about why I loved writing for Kerry. In early 2021, we ran into each other in between Grace and Flanner halls, where we often met, and he asked if I’d consider contributing an essay to the issue on the 50th anniversary of coeducation, scheduled for the following summer.

He got an earful from me. I told him it was my pet peeve that the branding around the 1972 anniversary focused erroneously on the “arrival” of women on Notre Dame’s campus. “You know what I’d really like to write an article about? The women who arrived on campus in 1843, who we don’t remember any more,” I said. He shrugged and said, “OK. Do that. I’ll put it in the issue before that one.” So I did, and I learned so much from writing the story and was proud to have it featured in the issue that celebrated the magazine’s 50th anniversary.

Kerry wasn’t the editor for all of those 50 years maybe, but he’s the only editor I have known, and I have trouble picturing the magazine without him. Come to think of it, I am having a hard time picturing Notre Dame without him on campus. Kerry and I talked often about Notre Dame, what we love about it and what we find maddening. He is a big part of what I love about Notre Dame. And I am going to miss him immensely.

— Kathleen Sprows Cummings ’99Ph.D., is the Rev. John A. O’Brien collegiate professor of American studies and history.

Words with friends

It wasn’t planned that way, but over the two decades that I’ve worked with Kerry Temple we’ve spent an inordinate amount of time juggling ideas about trees and books and the everlasting struggle with words.

I met Kerry in 2003. At first, over a table at the Hesburgh Center, we chatted in the way that writers, and editors who are writers, often do, skipping from one idea to the next, whisked along by the magic of words and the intractable process of writing. Notre Dame itself was most often the starting point, and our working relationship began with him giving me the nod to go ahead with an article about the soul of the University.

Those few meals were the only face-to-face meetings we ever shared. Since I left the Kellogg Institute for International Studies in 2004, our exchanges have been by phone or, more often, the digital smoke signals of email. It didn’t matter, because we came to communicate more effectively without using words at all. I read Kerry’s Back to Earth: A Backpacker’s Journey into Self and Soul in 2005 and realized that the connection between us ran much deeper than Notre Dame, deeper than journalism and publishing. We shared the journey along miles of backcountry trails the way military veterans share deployments. Trees and the world they inhabit had become the portal through which we discovered our true identities, and the path we followed as we took the measure of our souls.

Kerry made Notre Dame Magazine into The New Yorker of college publications. He showcased the achievements of the University, its faculty and its students. More than that, he strived to make the magazine interesting and relevant, setting it apart from most university-themed publications, which are rarely read. His handiwork was evident in the eclectic selection of stories in every issue — even those that were not about the University itself explored the concepts and beliefs that have made Notre Dame what it is. Readers couldn’t anticipate what the next issue would bring any more than reading a trail guide could offer the satisfaction of being outdoors. The next issue had to be opened, it had to be read for its treasures to be enjoyed, just as trails must be walked.

Though he lived for a time in a cabin in the backwoods, Kerry was no hermit. His gift was to relate what he experienced in nature to the wider world. As he wrote in Back to Earth, “It is one thing to revel in the beauty and order of creation; it is another to find it here among the people, the many nations with whom I live.” He did that, beautifully.

In each issue, Kerry set the tone in his editor’s note, artistically weaving his own experiences and outlooks with the reality being expressed in that issue. For the issue that carried my article about the awesome bristlecone pine trees of California, Kerry tackled the elephant in the room head on. “Yes, this issue’s cover story is about a kind of tree. But it is not just about a tree, not even really about what may be the oldest living thing on earth, which the bristlecone pine is believed to be. The cover story is about life.”

My experience with the bristlecone pines as a young man destined to write, and then, decades later, as a man who’d lived his life in the employment of words, had led me to an ongoing exploration of resilience, of how some species like the bristlecones can survive for 5,000 years, just as some collections of words can become immortal. The bristlecones survive in the harshest conditions of high sierra California, and the adversity they face only makes them more resilient. Kerry’s long tenure at the magazine, through many changes in his own life and the life of a major university, expresses that same resilience.

In Back to Earth, Kerry wrote about personal struggles and the way he had temporarily lost the trail. He found his way back, and for that we all are thankful. In the last article about trees and trails that we worked on together for the autumn 2023 issue, Kerry challenged me to dig deeper, to think harder, to write more directly from the heart. He apologized for sending the article back to me for a rewrite, but it was absolutely the right thing to do. There was a lot of good in the original, and he particularly liked the connection I had made between books and the trees they are made from because they both provide what we, at times, need most.

A good editor makes a writer and his words better. In the world of words, there’s no greater judgment. In his editor’s note, Kerry encouraged readers to think of the magazine as a gift, and to consider my essay about books, trees and trails, along with all the others in that issue, and by extension all issues of all magazines and all books, as gifts from writers sharing themselves with strangers.

Kerry made all his writers better. And Notre Dame is better for that.

Thanks for the gift, Kerry Temple.

Thanks.

— Anthony DePalma is a former correspondent for The New York Times and the author of several books, most recently The Cubans: Ordinary Lives in Extraordinary Times.

Inviting opportunities

Kerry, it has been more than a pleasure — really a joy — to work with you. And your suggestion that I should write for the magazine has been truly consequential in my life as a writer. You opened a door I couldn’t find, much less open, on my own.

A few years ago, I read from my work at the University of Portland, then went to supper with Brian Doyle ’78, the essayist who was also editor of the university magazine. Up the street from the restaurant, a theater marquee indicated that Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds were playing at that very moment, and I regretted not knowing about the show in advance: It would have been something to see and hear Nick Cave in Doyle’s company.

Then Brian died. I regretted not getting to know him better and not keeping up with his essays as steadily as they were published: They were so full of vitality, so radiant with the author’s character, that I’d assumed we could count on them coming out more or less endlessly. His work appeared to me as a road not taken — a road I hadn’t taken myself and may have avoided taking, in writing two long books rooted only obliquely in my own character and experience.

Out of my regret emerged a kind of resolution. I resolved I would find a way to write some work of that kind. For one thing, Brian’s death was a reminder that time’s-a-wastin’, and we shouldn't miss the chance to enter what we have seen and heard into the record. For another, my first book — where the “I” appears only in an epilogue — was grounded in the premise that the four writers it depicted gained their authority precisely because of the emphasis they gave to their own character and experience.

Years passed. I wrote long nonfiction pieces about Pope Francis and about the clerical sexual-abuse crisis. I started a third book, making my own character more present than in the first two — but wound up scaling it back on a trusted editor’s advice.

Then came your invitation to write for Notre Dame Magazine. It was open-ended. Three years in a row, you asked me what I might like to write. I suggested topics. You said yes, and yes, and yes. So I wrote the pieces; you, and John Nagy ’00M.A., edited them, lightly and expertly, and arranged for illustrations and typography, and they appeared in the magazine — more vivid and etched than I could have imagined them. An essay about Rome, rooted in my experience of the place; an essay about Notre-Dame de Paris, rooted in my experience of the Gothic in Paris, in New York, in literature and history; an essay about St. Paul, rooted in my long experience of uneasy identification with him. Those pieces have been crucial to my life as a writer, and now that they are written I can’t imagine the writer I’d be if I hadn’t written them. Through them, my own experience has been joined to that of the writers whose pilgrimage I’ve written about, and some half-understood obligation to make sense of the life that is mine only has been met partway.

I suspect that some of the gratitude I have felt comes through in the pieces. I hope so. And I hope to keep walking through the door you opened. Many, many thanks.

— Paul Elie is a senior fellow in Georgetown University’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs and a regular contributor to The New Yorker.

The heart of the place

It’s a running joke in my family that no matter how many formative years I spent at Notre Dame, every time I return to campus, I manage to get lost. Buildings rise and fall, roads appear and disappear, landmarks are moved and modified, and I’m forced to turn the car around or stop and retrace my (and everyone else’s) steps.

But no matter how much my mental geography may need a revision when Juniper Road disappears or new dorms are plopped next to Knott, I still know the location of Notre Dame’s heart. It’s wherever Kerry Temple is.

Editors come in all varieties, from the lackadaisical to the puritanical; Kerry, however, stands as his own unique vintage. He has great faith in writers but is not shy in letting you know if you missed the mark. He gives you room to breathe with choices of word, detail, reporting and structure, but will call a foul if you lose the opportunity to explore how a passing story can be illustrative of more eternal truths. And he understands how the artistic freedom of one person needs to interact and overlap with that of another within the confines of the increasingly archaic but ever more sacred confines of a physical magazine.

As the steward of what he always called “Notre Dame stories,” Kerry has indeed been the faithful curator of the Notre Dame story, in all its successes and failures, its aspirations and its heartbreaks, its contradictions and its beauty. He knows that a university is ultimately just an institution, and institutions are destined to be as fallible as humans and to evolve just the same, sometimes in directions we don’t like. But he also knows that a university like Notre Dame is home to a messy confluence of ideas and efforts that, at their best, can also be our surest vessel for considering our lives here on earth, and what they may — and should — mean beyond ourselves and the limited time we have to make them matter.

I think that’s the source of his fundamental decency and his appreciation of how picayune, pastoral and even normal are the glimpses of blessed eternity we get. I think it’s why he has such an appreciation for the world and its smallest creatures. I think’s it’s why he loves baseball in its unhurried perambulations. And I think it’s why he writes so eloquently about memory, time, childhood and a thousand other things.

I owe him a lot as a writer, in that he gave me the space and trust necessary at an early stage in my career to explore everything from the meaning of personal style to the legacy of family and national origin. I owe him more as a person, in that he showed how to question and interrogate one’s perspective in the way of water — gently but persistently. During one editorial meeting in a context long forgotten, I remember making some youthful crack about the absurdity of fish having souls. His direct and soft response was, “They do. You can see it in their eyes.”

I think about that every time I walk through the woods behind my house and come face to face with deer, foxes, squirrels and occasionally snakes. It’s a shame we can only gesture toward the wisdom that may be discovered in the quiet and the natural, but that is no reason to stop trying.

So in the future when I return to Notre Dame and inevitably get lost, it will be a shame that the school’s heart will no longer always beat within the confines of campus. But I take comfort from the fact that everyone Kerry has edited, worked with, befriended, mentored and spent time with surely also has a heart that tries to beat, even if only once in a while — be it at a baseball game, during a late summer sunset or when writing a final sentence — in the same rhythm.

— Liam Farrell ’04 is a former senior alumni editor of this magazine.

An editor who edited

I’ve always gotten a kick out of the correspondence between editors and writers — Maxwell Perkins, editor at Scribner, who wrote lengthy editorial letters to F. Scott Fitzgerald, or Katharine White, fiction editor of The New Yorker, who had so many exchanges with the poet Elizabeth Bishop over the decades that an entire fat volume of their correspondence has been published.